OBITUARY

(commissioned by The Times, 25 April 2008)

—————————————————–

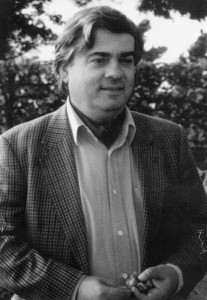

- Eugene Ionesco

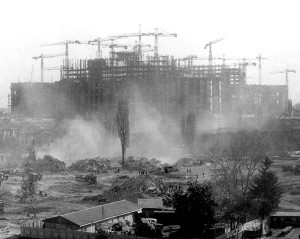

- Nicolae Ceausescu

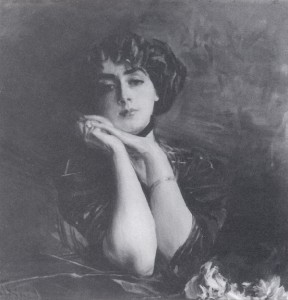

Monica LOVINESCU

(19 November 1923, Bucharest – 20 April 2008, Paris)

Romanian francophone Journalist, broadcaster, literary critic, political analyst, anti-communist and human rights activist, exile in France

———————————————————————————————-

Journalist and broadcaster Monica Lovinescu, was born in 1923, in Bucharest, the daughter of literary critic Eugen Lovinescu and Ecaterina Bàlàcioiu. She graduated with an M.Litt. in 1946 and after being granted a scholarship by the French government left for Paris in 1947. By the time Romania was declared a People’s Republic and the Iron Curtain had come down, Lovinescu was granted political asylum. As a literary critic and journalist surviving on the written word alone, Lovinescu could not have anticipated the climate confronting Romanian exiles in post-war France, which she recalled in her memoirs:

‘The French intellectuals not only positioned themselves to the left, but they were already mentally ‘sovietised’. Any attempt at opening the eyes of those intellectuals to make them more receptive to the plight of their fellow professionals in Eastern Europe was rejected as ‘fascist’ as soon as they declared themselves anti-communists’.

Such differences were the source of ongoing intellectual battles for the hearts and minds in French society, in spite of such revealing events as occurred in Hungary 1956, Czechoslovakia in 1968, or Gdansk in 1981. Even after the fall of Berlin wall in 1989, East European exiles were still branded as ‘visceral anti-communists’, an indictment intended to silence through isolation. Yet in spite of such dictums as Jean-Paul Sartre’s (‘the anti-Communist is a dog’),

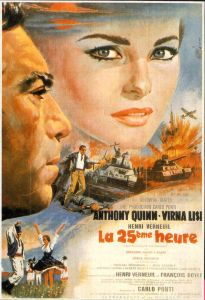

Lovinescu was not for turning. Monica Lovinescu instead took up the role of freelance translator, publishing in her adoptive country many Romanian novels including Virgil Gheorghiu’s best seller La vingt-cinquième heure. Her translation was adapted for the big screen in The 25th Hour (1967) by Carlo Ponti, starring Anthony Quinn and Michael Redgrave.

Lovinescu was not for turning. Monica Lovinescu instead took up the role of freelance translator, publishing in her adoptive country many Romanian novels including Virgil Gheorghiu’s best seller La vingt-cinquième heure. Her translation was adapted for the big screen in The 25th Hour (1967) by Carlo Ponti, starring Anthony Quinn and Michael Redgrave.

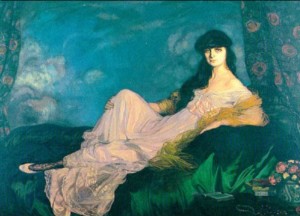

Lovinescu also acted as an informal literary agent for her friend Eugène Ionesco, whose play The Bald Primadonna she recommended to avant-garde theatre director Nicolas Bataille, introducing Ionesco as ‘a young playwright with a funny name’. Bataille instantly liked the play, which ends with the audience being ‘shot’, and although Lovinescu was a joint producer she insisted her name be omitted from the posters.

In her unassuming fashion, it was typical of Lovinescu to maintain that her contribution to Ionesco’s reputation was ‘inessential’. In retrospect, however, her vision was clear and message forthright. Her persistence paid off and soon the play was winning the plaudits of such seasoned critics as André Breton, Raymond Queneau, and Albert Camus. In the end the French public followed suit and the Theatre of the Absurd gained recognition.

Monica Lovinescu always remained devoted to her circle of Romanian exiles which included Mircea Eliade and Emil Cioran, but increasingly grew weary of acting as an intermediary for other authors. Instead she decided to dedicate more time to a career in broadcasting and journalism. She produced a huge number of articles in a myriad of cultural and political periodicals: East Europe, Kontinent, Preuves, L’Alternative, Les Cahiers de L’Est, Témoignages, La France Catholique, to name but a few and in the Romanian press in exile: Luceàfarul, Caiete de Dor, Fiinta Româneascà, Ethos, Contrapunct, Dialog, Agora.

Most importantly Lovinescu’s broadcasting activities had a much wider international impact, especially in Romania, where her contribution to literary criticism, as much as to political analysis, were the subject of regular transmissions on Radiodiffusion Française and Radio Free Europe. Henceforth the voice of Monica Lovinescu became synonymous to the voice of freedom and a lifeline for those listeners behind the Iron Curtain, hitherto deprived of any alternative views. Monica Lovinescu’s ‘Thèses et Anti-Thèses’ and the ‘Current Romanian Culture’ series would dispel the smoke screen of communist propaganda.

This was particularly important at a time when Nicolae Ceuasescu, the shoemaker dictator became the ‘darling’ of the West with his avowed ‘anti-Soviet’ stance. By contrast Monica Lovinescu’s was a singular, if discordant voice. She consistently resisted the psychological pressure of those ‘agents’ which she perceived as a real threat to Western civilization and which were bent on destroying it.

Lovinescu could see clearly through Ceausescu’s own brand of national communism, the myth of popular support he enjoyed at home and the ‘originality’ of his ideas. Lovinescu dismissed such humbug saying:

These lies are at the root of a suicidal complicity between the hangman and his victims. It is through this very act that we secured for ourselves our ‘originality’ within the communist context. The antagonism between ‘Them’ and ‘Us’, (…) dissolved in the derisive. On that tragic Shakespearean stage all characters of prime stature had disappeared, leaving behind only the buffoons, whose ribaldry is hollow.

Lovinescu’s tremendous media activities attracted the inevitable attention of the régime in Bucharest at a time when silencing the voices at home was defined by utmost brutality. In 1958 her 71-year-old mother was arrested, the family flat in Bucharest was ransacked, books and papers either burnt or confiscated. Lovinescu’s mother was incarcerated and given an eighteen-year sentence for ‘undermining the State order and passing secrets to a foreign power’. The sentence was then, as was customary, bartered against her daughter’s return to Romania, a deal that her mother refused. She died shortly thereafter, only two years into her 18 year sentence, aged 72, having been refused all medical attention, her body thrown into an unmarked grave.

But her personal tragedy only steeled Monica’s resolve to fight for human rights. During the 1970’s and 80’s Ceausescu resorted to more brutal action abroad. Four of Monica’s colleagues at Radio Free Europe in Munich were either assassinated or died in suspicious circumstances and other prominent Romanian exiles received letter bombs. Ceausescu himself took control of the operations and Carlos ‘the Jackal’ was instructed to carry out retribution.

According to General Ion Pacepa, the deputy chief of the Romanian foreign intelligence services and defector, Ceausescu was reputed to have instructed his henchmen:

Monica Lovinescu must be silenced, not killed. I do not need any uncomfortable French and American investigations… I want her to become a living corpse. Use foreign hands, so that no evidence can turn up that could lead back to the Romanian connection.

In 1977, Lovinescu was attacked by a hired PLO hit squad outside her Paris home. Luckily the assailants fled as neighbours were alerted but the victim was still left with severe head injuries. She revived from her hospital coma only to resume her crusade with a handful of Romanian friends including Marie-France Ionesco, Sanda Stolojan and Michel Foucault, the French Marxist and Structuralist philosopher. They exposed Ceausescu’s atrocities at anti-totalitarian vigils in front of the Romanian embassy in Paris.

Monica Lovinescu outlived Ceausescu whose exit culminated in his televised trial and execution in 1989. Ten years on, in recognition of her life-long contribution to Romanian political and cultural life, Ms Lovinescu was awarded the Order of the Star of Romania, by the democratic-liberal President, Emil Constantinescu.

Asked in April 2002 about her opinion on the desirability of a Nuremberg-style trial of communism, Lovinescu answered:

The trial of communism might have offered Romanian mentality a real chance for change. The handful of initiatives taken so far are built entirely on moving sands. We cannot consider a Nuremberg-style trial simply because that involves winners and losers. Or, in this particular instance, communism lost its own war: it simply imploded, not exploded. But one should consider at least a moral prosecution. It is impossible to contemplate the fact that torturers in Romania have not been yet morally indicted.

Monica Lovinescu, M.Litt., Grand Officer, Order of the Star of Romania, was married to fellow journalist, literary critic and political analyst Virgil Ierunca (1920-2006). They leave no children and their estate has been bequeathed to a Romanian government foundation.

Constantin Roman © 2008-2009. All Rights Reserved.

NOTE:

The Romanian Media has translated (with predictable liberal approximation) the Times Obituary of Monica Lovinescu. However what was truly striking (although perhaps unsurprising) is that ALL, but absolutely ALL newspapers without exception have applied that ubiquitous expectation of “self-censorship” which required them to omit ANY reference to the defector and ex-Securitate General Ion Pacepa as well as to Ceausescu’s practice of ordering the murder and intimidation of dissidents: in a 2009 Survey on the Freedom of the Press (or lack of it) Romania came 85th amongst all the countries of the World – not bad at all for a country which claims to be democratic but cheats on Democracy, twenty years after the dictator was put down!

The above text is unabridged, as it was published in the London Times, in April 2008.

For MORE INFORMATION about the DESTINIES OF ROMANIAN WOMEN, read the E-Book Anthology:

“Blouse Roumaine – the Unsung Voices of Romanian Women”

An Alternative Anthology of Romanian Women