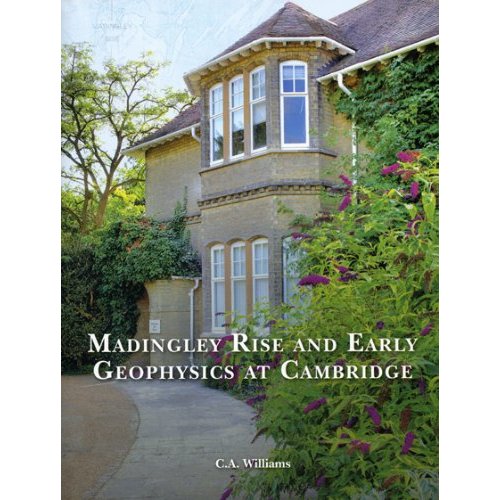

Interior Orthodox Vilage Church _ Gorj County, Romania

« ALE MORTULUI » (Gorj) culegere de Constantin Brâiloiu *

(BOCET transcris de Petru Comarnescu** si Mircea Milcovitch***)

I

Zorilor, zorilor, / Voi surorilor, / Voi sà nu pripiti, / Sà ne nàvàliti, / Pînâ si-o gàti, / Dalbul de pribeag, / Un cuptor de pîine, / Altul de màlai, / Nouà buti de vin, / Nouâ de rachiu, / Si-o vacuta grasà, / Din ciread-aleasà, / Sà-i fie de masà. /

II

Zorilor, zorilor, / Voi surorilor, / Voi sà nu pripiti, / Sà ne nàvàliti, / Pînâ si-o gàti, / Dalbul de pribeag, / Turtità de cearà, / Fie-i de vedealà, / Vàlusel de pînzà, / Altul de peskire, / Fie-i de gâtire. / Zorilor, zorilor, / Voi surorilor, / Voi sà nu pripiti, / Sà ne nàvàliti, / Pînâ si-o gàti, / Dalbul de pribeag, / Un car càràtor, / Doi boi tràgàtori, / Cà e càlàtor, / Dintr-o lume-ntr-alta, / Dintr-o tarà-ntr-alta, / Din tara cu dor, / In cea fàrà dor, / Din tara cu milà, / În cea fàrà milà, /

III

Zorilor, zorilor, / Voi surorilor, / Voi sà nu pripiti, / Sà ne nàvàliti, / Pînâ si-o gàti, / Dalbul de pribeag, / Nouà ràvàsele, / Arse-n cornurele, / Ca sà le trimeatà, / Pe la nemurele, / Sà vinâ si ele, / Sà vadà ce jele. /

IV

Bradule, bradule, / Cin’ ti-a poruncit, / De mi-ai coborît, / De la loc pietros, / La loc mlàstinos, / De la loc cu piatrà, / Aicea la apà ? / Mi’ mi-a poruncit, / Cine-a pribegit, / Cà i-am trebuit, / Vara de umbrit, / Iarna de scutit. / La mine-a mînat, / Doi voinici din sat, / Cu pàrul làsat, / Cu capul legat, / Cu rouà pe fatà, / Cu ceata pe brate, / Cu berde la brîu, / Cu colaci de grîu, / Cu securi pe mînà, / Merinde de o lunà, / Eu dacà stiam, / Nu mai ràsàream; / Eu de-as fi stiut, / N-as mai fi crescut. /

V

Si ei au plecat, / Din vàrsat de zori, / De la cîntâtori, / Si ei au umblat, / Vàile cu fagii, / Si muntii cu brazii, / Pînâ m-au gàsit, / Bradul cel pocit, / Pe min’m-au ales, / Pe izvoare reci, / Pe ierburi întregi; / Pe cracà uscatà, / De moarte làsatà. / Ei cînd au venit, / Jos au hodinit, / Au îngenunchîat, / De-amîndoi genunchi / Si s’au închinat; /

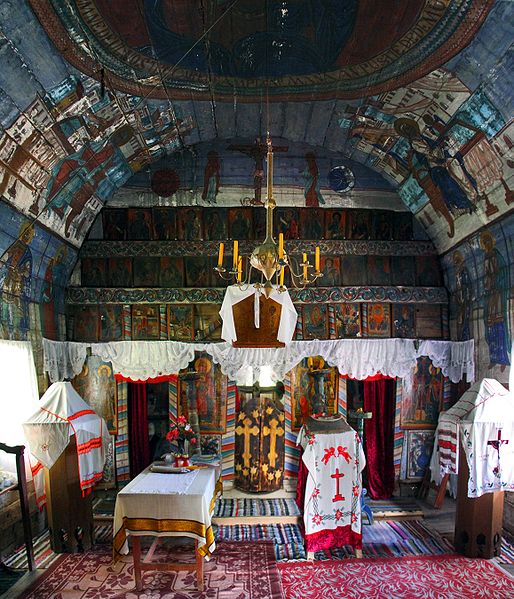

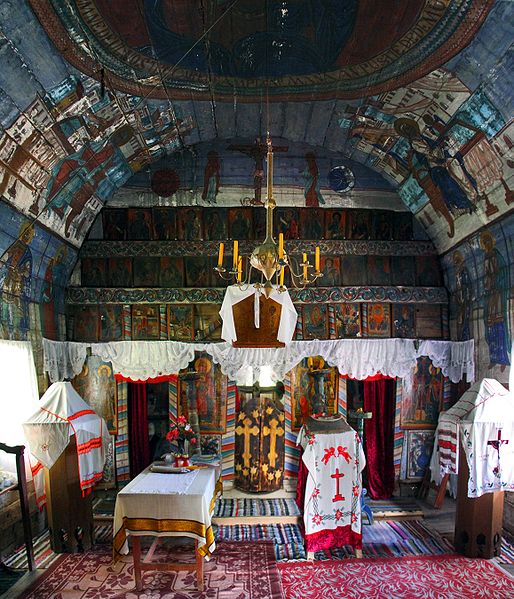

Ancient altar screen (Iconostasis) in the wooden village church of Pojogeni, County GORJ, Romania

VI

Laràs-au sculat, / Cu securi-au dat, / Jos m-au doborît, / M-au pus la pàmînt, / Si ei cà m-au luat / Tot din munti în munti, / Prîn bràdui màrinti, / Tot din vài în vài, / Prin brazi màruntei, / Dar ei nu m-au luat, / Ca pe alte lemne, / Si ei cà m-au luat / Tot din vale-n vale, / Cu cetina-n vale, / Sà le fiu de jale; / Cu poale làsate, / A jale de moarte. / Eu dacà stiam, / Nu mai ràsàream ; /

VII

Eu de-as fi stiut, / N’as mai fi crescut. / Cînd m-au doborÎt / Pe min’ m-au mintit, / C-au zis cà m-or pune, / Zînà la fîntînà, / Càlàtori sà-mi vinâ; / Si-au zis cà m-or pune / Tàlpoaie de casà, / Sà mà sindileascà, / Cu sindrilà trasà / Dar ei câ m-au pus, / În mijloc de cimp, [1] / La cap de voinic, / Cîinii sâ-i aud, / A làtra pustiu, / Si-a urla mutiu, / Si sà mai aud, / Cocosii cîntînd, / Muieri mimàind, / Si preoti cetind; /

VIII

Ploia sà mà ploaie, / Cetina sà-mi moaie; / Vîntul sâ mà batà, / Cetina sà-mi cadà; / Ninsoarea sà ningà, / Cetina sà-mi frîngà, / Eu daca stiam, / Nu mai ràsàream; / Eu de-as fi stiut, / N-as mai fi crescut, / Ei cînd m-au tàiat, / Ei m-au îmbunat / Cà ei ma sàdesc, / Nu mà secuesc. / Si ei m-au mintit, / Cà m-au secuit, / Jos la ràdàcinà, / Cu fum de tàmîie; / Mai pe la mijloc, / Chitii de busuioc, / Tot milà si foc, / Sus la crîngurele, / Chiti de ochesele, / Tot milà si jale. / Eu dacà stiam, / Nu mai ràsàream. / Eu de-as fi stiut, / N’as mai fi crecut. /

IX

Ridicà, ridicà, / Gene la sprîncene, / Buze subtirele, / Sà gràesti cu ele, / Cearcà, dragà, cearcà, / Cearcà de gràeste, / De le multumeste, / La strin, la vecin, / Cui a fàcut bine / De-a venit la tine, / Cà ei si-au làsat / Hodina de noapte / Si lucrul de ziuà, / Eu nu pot, nu pot, / Nu pot sà gràesc, / Sà le multumesc, / Multumi-le-ar Domnul, / Cà eu nu li-s omul. /

X

Eri de dimineatà / Mi s-a pus o ceatà, / Ceatà la fereastrà, / Si-o corboaicà neagrà, / Pe sus învolbînd, / Din aripi plesnind, / Pe min’m-a plesnit, / Ochi a-mpànjenit, / Fata mi-a smolit, / Buze mi-a lipit. / Nu pot sà gràesc, / Sà le multumesc. / Multumi-le-ar Domnul, / Cà el mi-a dat somnul; / Multumi-le-ar Sfintul, / Cà el mi-a luat gîndul. /

Village cemetery, County Gorj, SW Romania

XI

Scoalà, Ioane, scoalà, / Cu ochii priveste, / Cu mîna primeste, / Cà noi am venit, / Cà am auzit, / Cà esti càlàtor, / Cu roua-n picioare, / Pe cea cale lungà, / Lungà, fàrà umbrà. / Si noi ne rugàm / Cu rugare mare, / Cu strigare tare, / Seama tu sà-ti iei, / Seama drumului, / Si sà nu-mi apuci, / Càtre mîna stîngà, / Cà-i calea nàtîngà, / Cu bivoli aratà, / Cu pini semànatà, / Si-s tot mese strînse, / Si cu fàclii stinse, /

XII

Dar tu sà-mi apuci / Câtre mîna dreaptà, / Cà-i calea curatà, / Cu boi albi aratà, / Cu grîu semànatà, / Si-s tot mese-ntinse / Si fàclii aprinse. / Nainte sà mergi, / Sà nu te sfiesti, / Dacà mi-ei vedea / Ràchità-npupitâ, / Nu est ràchità, / Ci e Maica sfîntà. / Nainte sà mergi, / Sà nu te sfiesti, / Dacà mi-ei vedea / Un pom înflorit, / Ci e Domnul sfînt. / Nainte sà mergi, / Sà nu te sfiesti, / Dacà-ai auzi / Cocosii cîntînd, / Nu-s cocosi cîntînd, / Ci-s îngeri strigînd. /

XIII

Nainte-I mergea / Si mi s-o fàcea / Tot un bîlciulet. / Si sà te opresti,/ Ca sà-mi tîrguiesti / Cu banul din mînà / Trei mahrame negre, / Trei sovoane noi / Si trei chiti de flori. / Si t-i-or mai iesi / Tot trei voinicei. / Mîna-n sîn sà bagi, / Mahrame sà tragi, / Sà le dàruiesti, / Vama sà plàtesti. / Si ti-or mai iesi / Tot trei nevestele./

XIV

Mîna-n sîn sa bagi, / Sovoane sà tragi, / Sà le dàruiesti, / Vama sà plàtesti. / Si ti-or mai iesi / Tot trei fete mari. / Mîna-n sîn sà bagi, / Chiti de flori sà tragi, / Sà le dàruiesti, / Vama sà plàtesti. / Seara v-nsera, / Gazdà n-ai avea / Si-ti va mai iesi / Vidra înainte, / Ca sà te spàimînte, / Sà nu te spàimînti, / De sorà s-o prinzi, / Cà vidra mai stie / Seama apelor / Si-a vadurilor, / Si ea mi te-a trece, / Ca sà nu te-nece, / Si mi tea purta, / La izvoare reci, / Sà te ràcoresti / Pe mîini pîna-n coate / De fiori de moarte. /

XV

Si-ti va mai iesi / Lupul înainte, / Ca sà te spàimînte. / Sà nu te spàimînti, / Frate bun sà-l prinzi, / Cà lupul mai stie /Seama codrilor / Si-a potecilor. / Si el te va scoate / La drumul de plai, / La un fecior de crai, / Sà te ducà-n rai, / C-acolo-i de trai; În dealul cu jocul, / C-acolo ti-e locul ; / ’n cîmpul cu bujorul, / C-acolo ti-e dorul. / Si-acolo la vale, / Este-o casà mare, / Cu feresti la soare, / Usa-n drumul mare, / Strasina rotatà, / Strînge lumea toatà, / Acolo cà este / Mahalaua noastrà, / Si-ti vor mai iesi, / Tineri si bàtrîni, / Tot cete de fete, / Pîlcuri de neveste. / Sà te uiti prin ei, / C-or fi si de-ai mei. /

XVI

Ei cînd te-or vedea, / Bine le-o pàrea / Si te-or întreba : / Datu-le-am ceva ? / Bine sà le spui, / Cà noi le-am trimes / Lumini din stupini / Si flori din gràdini ; / Si iar sà le spui, / Anume la toti, / Cà noi i-asteptàm / Tot la zile mari, / Ziua de Joimari, / Cu ulcele noi, / Cu stràchini cu lapte, / Si cu turte calde; / Cu pahare pline, / Cum le pare bine ; / Cu haine spàlate, / La soare uscate, / Cu lacrimi udate. /

XVII

Roagà-mi-te, roagà / De copiii tài, / Sà aibà ràbdare, / Sà nu plîngà tare, / C-acum nu-i pe dare, / Ci e pe ràbdare. / Cà de-ar fi pe dare, / Sotul tàu ar da / Plug cu patru boi / Cu plugar cu tot, / Doarà mi te-a scoate / De la neagra moarte ; / Dar nu e pe dare, ‘/ Ci e pe ràbdare. ‘/ Cà de-ar fi pe dare, / Sotul tàu ar da / Ciopàrel de miei, / Cu cioban cu tot / Si oile toate, / Doarà mi te-a scoate / De la neagra moarte ; /

XVIII

Dar nu e pe dare, / Ci e pe ràbdare. / La gurà de vale / Este-o ceartà mare. / Cine se certa ? / Soarele cu moartea. / Soarele zicea / Cà el e mai mare, / Cà el cînd ràsare, / El îmi încàlzeste / Cîte cîmpuri lungi, / Cîte vài adînci. / Moartea cà-mi zicea / Cà ea e mai mare / Cà ea mi se duce / Pe la bîlciuri mari / Si ea îsi alege / Voinici pe clipici. / Fete pe panglici; / Voinici tinerei / De care-i place ei; / Fete tinerele, / Sà plîngà cu jele. /

XIX

Scoalà, Ioane, scoalà, / Scoalà-te-n picioare, / Te uità la vale, / Vezi ce-a tàbàrît; / Un cal mohorît / Cu tolul cernit, / Cu scàri de argint. / Chinga-i poleità, / Seaua e boltità, / Frîu de màtasà, / Sà te ia de-acasà. / Sus, bradule, sus, / Sus de càtre-apus, / Cà la ràsàrit / Greu nour s-a pus. / Nu-i nour de vînt, / Ci e de pàmînt, / De tàrînà nouà, / Neatinsà de rouà, / Pe unde-a umblat, / Rea jale-a làsat; /

XX

Pe unde-a bàtut, / Rea jale-a fàcut. / Roagà-mi-te roagà / De sapte zidari, / Sapte mesteri mari, / Zidul sà-l zideascà / Si tie sà-ti lase / Sapte feràstrui, / Sapte zàbrelui. / Pe una sà-ti vinà / Colac si luminà ; / Pe una sà-ti vinà / Izvorel de apà, / Dorul de la tatà; / Pe una sà-ti vinà / Spicul grîului / Cu tot rodul lui; / Pe una sà-ti vinà / Buciumel de vie / Cu tot rodul lui; / Peu na sà-ti vinà / Raza soarelui / Cu càldura lui ; / Peu na sà-ti vinà / Vîntul cu ràcoarea, / Sà te ràcoresti, / Sa nu putrezesti. /

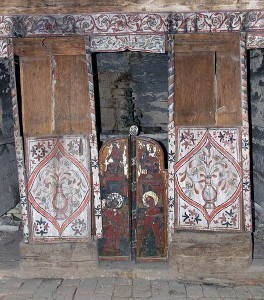

Vernacular Architecture from Brancusi's country - County Gorj, SW Romania

[1] Sau : In marea gràdinà

La cap de copilà /

—————————-

ADDENDUM – Note:

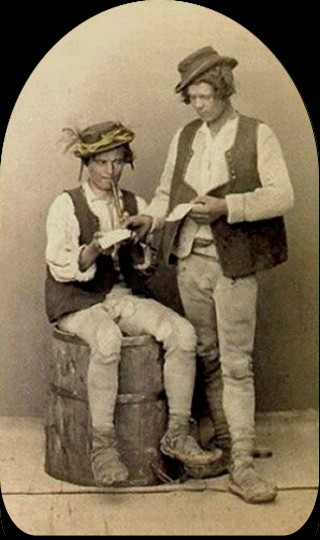

Teodor T. Burada (1839-1923)

folclorist, etnograf, nume de prestigiu în istoria muzicii,  descoperitorul bocetului popular

descoperitorul bocetului popular

Sava Garleanu scrie: “Un pelerin neastamparat strabatea cu neostenire, intre anii 1878-1900, toate meleagurile din lume pe unde se vorbea sau se mai vorbise in trecut limba romana, pe unde adica se aflau Romani. O facea cu dragoste, cu pasiune si daruire, cum n’a facut nimeni altul pana azi, nici macar cu mintea, dupa cum pare.

Acesta era ieseanul Teodor T. Burada (1839-1923), un intelectual polivalent, cunoscut muzician, jurist, folclorist si etnograf, nu mai putin istoric si literat, animator al teatrului romanesc.

Luandu-si in mana nedespartita-i vioara, T. Burada pornea in drumetie de fiecare data spre o alta provincie a “imparatiei limbii romanesti”. Prin cate un oras dadea concerte de muzica selecta, cultã. In sate insa, printre fratii Romani de pretutindeni, nu se sfia nicidecum sa fie un lautar de hora, cu priceperea sa si la melosul popular. Stabilea astfel repede comunicatiunea necesara cu cei de un neam. Comunica melodii din tara, luand totodata altele specifice romanesti pe corzile viorii sau pe foi de notatie. Nu aducea insa de pe unde calatorea numai melodii, ci cara cu sine “bagaje” intregi de comori folclorice si etnografice: balade, cantece de nunta, bocete: descrieri de costume, de case, mod de viata; de obiceiuri practicate in difeite imprejurari; lexic doveditor al unitatii limbii. Avea si avantajul de a cunoaste limbi straine, printre acestea greaca si chiar turca. Nu a neglijat sa adune si crestaturi de raboj, presupuse a fi fost scriere a Dacilor. Vechi notatii folclorice, acestea erau in orice caz.

Acolo unde sunt ape curgatoare, rabojul frant, de care se lipeste o lumanare, in alte parti intr-un ciob de oala, strachina de pamant sau alte obiecte plutitoare, in care se adauga si un colacel, se randuieste celui decedat si se lasa in curgerea apei, numita si “apa simbetei”. Ceremonialul este insotit adesea si de bocet, ca in Oltenia, de exemplu, si in Banat, de unde Teodor T. Burada ne-a pastrat un emotionant bocet din com. Picinis.

http://www.crestinortodox.ro/datini-obiceiuri-superstitii/refrigerium-mitologia-in-istoria-poporului-roman-68784.html

Mircea Eliade:

Mircea Eliade arata ca filosofii au atacat problema nemuririi sufletului, ceea ce este cu totul altceva decat problema supravietuirii post-mortem, si considera ca suntem indreptatiti sa cautam in istoria religiilor, in folclor si in etnografie, documente, urme de experienta concrete, cu ajutorul carora sa putem ataca dintr-un alt punct de vedere problema mortii, adica a supravietuirii sufletului, si justifica indreptatita afirmatia lui Lucian Blaga : “pentru cei de la sat moartea avea cu totul alta semnificatie decat pentru omul obisnuit de astazi. Sufletul mortului pleaca sa-si intalneasca fratii, rudele, prietenii in lumea cealalta.”

Cercetand simbolismul funerar la anumite popoare primitive si arhaice, ca si la poporul roman, Mircea Eliade constata un lucru semnificativ : simbolismul incepe sa se organizeze in “sistem”, in “metafizica”, adica sa devina cultura, numai cand se aplica asupra mortii, si cultura aceasta incepe prin a fi o prelungire a vietii, o promovare a principiilor creatoare si vitale. Nicaieri nu apare oboseala, tristetea, disperarea omului. Departe de a desparti pe om de natura, de a-l izola in mijlocul Cosmosului, aceasta cultura solidarizeaza pe om in acelasi timp cu viata, cu moartea si cu supravietuirea, cum suna si mesajul lui Blaga, expresie de fapt a mesajului poporului roman, oglindit semnificativ in creatia sa literara, Miorita, care reprezinta conceptia sau “ideea de reintegrare in Cosmos prin moarte” (M. Eliade).

http://www.crestinortodox.ro/datini-obiceiuri-superstitii/refrigerium-mitologia-in-istoria-poporului-roman-68784.html

Lucian Blaga:

“Dar, ca unul care am trait toata copilaria in sat, inteleg foarte bine problema supravietuirii, caci pentru cei de la sat moartea avea cu totul alta semnificatie decat pentru omul obisnuit de astazi. Sufletul mortului pleaca sa-si intalneasca fratii, rudele, prietenii in lumea cealalta. Este vorba deci de o comunitate a “celor dusi”. De aceea nici durerea in fata mortii nu este atat de tragica la sat. Imi amintesc plansul mamei la moartea unui fecior, pe care-l iubea ca ochii din cap. Ei bine, era un plans linistit, impacat…”.

Constantin Brâiloiu * (1893, Bucuresti – 1958, Geneva)

Nascut in Bucuresti si educat in Europa occidentala Brailoiu a fost diplomat, estet, etnolog si muzicolog exilat in Elvetia dupa al doilea razboi mondial. El este conisderat Parintele Etnomuzicologiei: si ca atare, impreuna cu Eugene Pittard, este initiatorul si fondatorul AIMP Arhivelor Internationale de Muzica Polulara de la Geneva. In ultimii 15 ani din viata a cules si organizat cel mai mare fond de arhiva de muzica populara din intreaga lume, inregistrat la inceput pe discuri de 78 de ture si ulterior re-editat intr-o colectie de compact-discuri CD.

http://www.ville-ge.ch/meg/brailoiu.php

Petru Comarnescu**(1905 iasi – 1970, Bucuresti)

Petru Comarnescu a transcris Bocetul din Gorj cules de Conastantin Brailoiu transmitandu-l mai departe lui Mircea Milcovici (Milcovitch). Comarnescu a fost unul dintre cei mai importanti istorici de arta din Romania, luandu-si doctoratul la Universitatea din California, la Los Angeles. In perioada imediat dupa al doilea razboi mondial, sub regimul cenzurei lui Gheorghiu-Dej publicatiile lui au fost limitate la monografii de arta si traduceri literare, dar nu si de estetica sau filosofie.

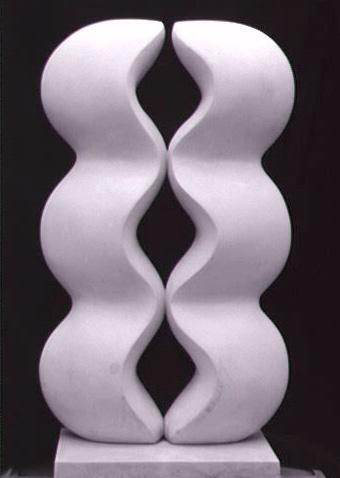

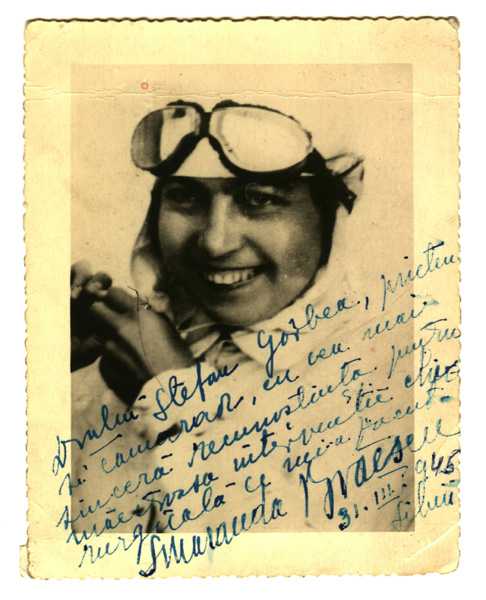

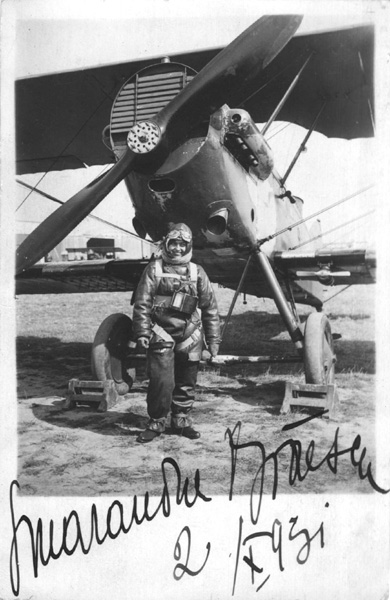

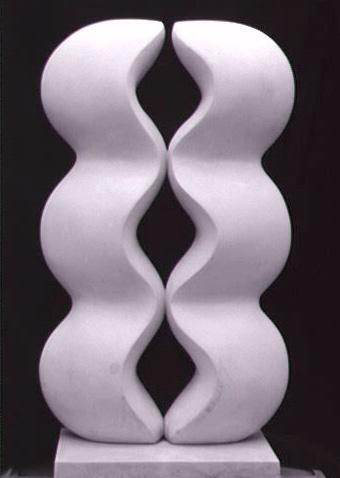

Mircea Milcovitch*** (n. 1941) care ne-a transmis “Bocetul” din Gorj este nascut in Romania unde a studiat la Institutul Pedagogic Facultatea de Arte Plastice, dupa care s-a stabilit in Franta. Artist sculptor de reputatie mondiala, lucrarile lui Milcovitch in majoritate in marmura de Carrara sunt prezente in muzee si colectii din Franta si din intreaga lume.

http://www.milcovitch.net/

http://www.vincentroman.com/blog/mircea-milcovitch-nude-shapes-and-forms/

Milcovitch - Objet Hermetique (Carrara Marble)

NB Iata o observatie facuta de catre Mircea Milcovici in care face o trimitere la “poezia siriaca”:

Je feuilletais une revue littéraire de 1996 me demandant si je la garde ou la jette, et y trouvais avec étonnement la traduction des “Hymnes sur la Nativité” d’Ephrem le Syriaque. J’y remarquais la disposition typographique qui me rappelait le rythme des “bocete” d’Olténie recueillis par Brailoiu. L’introduction dit que les hymnes sont précédés du titre syriaque de “nusrâté”, qui signifie “berceuses”. Or, j’ai toujours eu l’impression que les boceté avaient un rythme “legànat” (mot roumain) de berceuse, l’idée de berceuse étant tout à fait applicable aux chants au chevet d’un homme endormi pour l’éternité, dont l’âme n’est pas morte mais et est mise en attente de la Résurrection ! La même introduction dit que la structure métrique des Hymnes est de quatre syllabes pour chaque vers, ce qui correspond avec celle des bocete. Puisque j’ai les “Hymnes sur le Paradis” du même Ephrème dans une bonne édition, je lisais ce qui était écrit quant aux vers et à leur rythmique. On y trouve là des strophes comprenant de cinq sillabes groupés deux par deux, avec, au milieu de la strophe, un vers de deux sillabes pour rompre la monotonie. On peut trouver dans les bocete des strophes similaires.

J’y lisais aussi que le principe de l’hymnographie syriaque était différent de la poésie religieuse classique grecque, reposant sur la quantité des syllabes et non la rime. Je cite: “En syriaque, il y a un nombre fixe de sillabes avec un retour régulier de l’accent: c’est un genre moins savant mais plus accessible pour un auditoire simple. C’est précisément le succès de ce genre de poésie syriaque qui fera traduire Ephrem en grec et donnera naissance à l’hymnographie byzantine…” (Ephrem de Nissibe, Hymnes sur le Paradis, Ed. du Cerf, Sources Chrétiennes 137, 1968)

PS. Voici juste deux strophes d’Ephrem, en français, donc le nombre des syllabes n’est pas le même qu’en syriaque, mais le rythme rappelle tellement ces “bocete”!

Voici le Mois

qui tout entier

Apporte joies:

franchise aux serfs

fiérté aux libres

couronnés aux portes,

délices aux corps;

de pourpre même

il fait joncher dans son amour

comme pour un roi.

Voici le Mois

qui tout entier

porte victoires,

libère l’esprit,

dompte le corps,

enfante Vie

chez les mortels;

son amour jette

livrées divines.

see more about Syriac poetry in:

http://www.syriacstudies.com/AFSS/Syriac_Articles_in_English/Entries/2008/2/22_THEMES_OF_SYRIAC_POETRY_-Mor_Ignatius_Aphram_Barsoum.html