'Orpheous' by Janet CREE (private collection, London)

Orpheus never turned up for tea

Looking at a painting by Janet Cree (1910-1992)

—————————————————————–

There is an instant fascination which this painting on panel offers the neophyte, as he identifies himself without any difficulty to the main personage – a scantily clad youth playing an antique lyra, surrounded by a bevy of entranced females, some prostrate with admiration, others overcome by pure love.

Orpcheus, because this is precisely the identity of our lucky young man, appears to be oblivious of the ecstatic atmosphere he creates around him as he is content playing on, regardless, while focusing his eyes on the horizon.

The painting is luminous, in shades of ivory white which dominate the panel, punctuated by pale and discreetly-coloured draping in the guise of clothes and darker greens of erect poplars. These are Lombardy poplars of a kind that one very rarely sees in England, because the painter, although being English herself and trained at a London Art School, she sets her subject in Italy.

For there is a pervasive “Italian feel” in the aura of this picture suggestive of an early Montegna, combined with a strong overprint of the British school of painting of the early 1930s… All in all, I should say, the painting conveys a very pleasant soothing air of some far-away garden of Eden, to which one might aspire but never gain access to. Hence the perpetual reverie that exudes this beautiful composition – more effective and prudent than taking a trip on a tablet of Ecstasy…

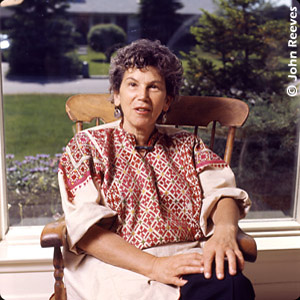

Our painter is called Janet Cree. Born in London in 1910, she is an artist of early promise as the Tate Gallery acquires one of her works when she is only 23 years of age. From then on we know little about her artistic fortunes and true to herself Janet carries on quietly with her craft, sending regularly her pictures to the RA exhibitions, without making waves. Soon the war takes its toll as the art aficionados go silent as the bottom falls out of the art market.

In spite of it all Janet Cree takes her due place in the dictionaries of contemporary British painters. Doubtless her family, as she sets up a home, makes demands on her time too,

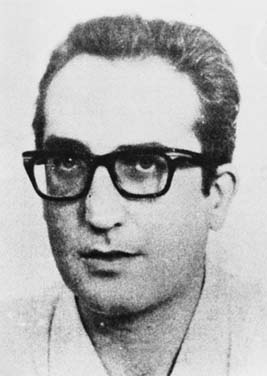

John Platts-Mills, QC, MP (1906-2001) defending Counsel for the Kray Brothers and the Great Train Robbers

for she is now married to a mercurial lawyer whose physical and social stature is larger than life: this is John Platts-Mills, the six-foot New Zealand-born athlete and Oxford-educated student. He comes to Britain as a Rhodes scholar to Balliol College.

By this time, the trauma of the First War takes its toll on the mood of the young people, who are disaffected with the society and over-enthusiastic about the social and economic ‘paradise’ promised by Joseph Stalin.

Platts-Mills is no exception. At first he hopes that luck may strike closer to the British Isles as he gives his support to the Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War. That was not to be. For a moment it seems that his political sympathies go astride the main flow of the British establishment, as he is not considered good material to enroll as a RAF pilot during the war. Earlier on, in 1932 he is called to the Inner Temple, but will not become a King’s Council for a long time, because of his political sympathies.

However, at the beginning of the war the Allied troops suffer many set backs, which cause Platts-Mills’ fortunes to change for the better, as Churchill calls on him and urge him to be a go-between with Stalin’s Russia. This is the time when Platts-Mills throws himself arduously into Soviet-British PR, forging endless Soviet-British friendship societies all over Britain. Yet, on the political board of snakes and ladders fortunes change quickly and with the advent of the cold war the maverick barrister looses his political clout: in the process he also looses his Finsbury seat in Parliament, as he is expelled from the Labour Party. But hard luck turns to good fortune as his reputation precedes him. He becomes a much sought-after lawyer in some of the most controversial legal cases, defending the Kray brothers, the Great Train Robbers, the Shrewsbury two. He also acts as a secret adviser of Trade Union leader Arthur Scargill in the miners’ strike of the 1970s, which caused the fall of Edward Heath’s government. He appears on the Grunwick picket line and acted on the Bloody Sunday inquiry in Londonderry.

But before he becomes involved in these high-profile cases Platts-Mills takes care to pay his last respects to “Uncle Joe”, as he dies in the Kremlin, in 1953.

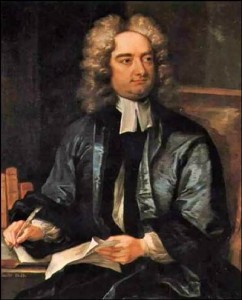

He is not alone in eulogising the infamous people’s executioner, as another fellow traveler and a Nobel Prize laureate, the Chilean Pablo Neruda depicts the Red dictator in heart-rending, sycophantic verse:

Red Dictator and Murderer Joseph Stalin: Platts-Mills attends his funeral in 1953

‘In three rooms of the old Kremlin

‘In three rooms of the old Kremlin

lives a man named Joseph Stalin

His bedroom light is turned off late.

The world and his country allow him no rest.’

And how! The fallen peoples of Eastern Europe know all about it in the new satellite prison-states that were occupied by Soviet troops.

This is no concern for our London lawyer who is fond of driving Rolls-Royces and Bentleys and decrees benevolently:

The Rolls-Royce - Platts-Mills preferred vehicle: he decreed that every working class man ought to have one!

‘Every working class man should have one!’

Quite so! And to start with those working classes could drive Rolls-Royces by proxy, through their representatives like Platts-Mills…and drink champagne also through their representatives.

Lybian dictator Col Gaddafi (by John Cox): visited by Mills at the time of the Lybian Embassy crisis in London

Clearly, John Platts-Mills had a fascination with more than one killer dictator, for, when his dutiful and self-effaced wife is somewhat surprised by his absence from home, she rings his Chambers to ask his whereabouts: well as it happened his image just appeared flittingly on British TV screens as a guest standing behind Colonel Ghaddafi, on a visit to Libya. This was the time of the Libyan embassy crisis in London, at which point the imperturbable Janet would answer quietly:

‘Well, in that case I will not lay out the table for tea.’

In her old age, the faithful and dutiful wife never questioned and never complained: for her the personage in the centre of her youthful painting was no other than her good-looking husband, the very iconic Orpheus who never turned up for tea.