Constantin Roman: “Continental Drift: Colliding Continents, Converging Cultures” Reviewed by Thomas G. Gallagher (Bradford University)

Constantin Roman: “Continental Drift, Colliding Continents, Converging Cultures”

Constantin Roman is Romanian Honorary consul in the English university town of Cambridge where he was awarded a PhD for pioneering work in the field of geophysics in 1974. For over twenty years, he has been an independent consultant in oil exploration and his reputation as a successful oil finder has enabled him to settle down comfortably in a pleasant corner of England after many vicissitudes.

Dr Roman’s memoirs were published in 2000 by an Anglo-American scientific publisher. The title, Continental Drift suggests that plate tectonics, his field of expertise, dominates the book. In fact while frequent attention is given to his scientific ideas, how they were applied, and the collaboration with eminent scientists which resulted, the fascination of this book is to be found in its account of how the human spirit managed to triumph over considerable odds.

Roman is a determined and ingenious Romanian with a gift for striking up friendships with the eminent and the humble and also a genius for improvisation, which has extricated him from tight corners. Such survival skills, when not leavened by strong moral qualities, have produced a rather sinuous Romanian, immortalised by the playwright Caragiale, and much seen in the politics of the country for the past seventy years.

Roman ‘s ability to triumph against the odds and make a new life for himself in a land very different from the one he left, while retaining a strong moral formation and a desire never to lose touch with Romania, is a gripping and inspiring tale. It is one that young talented East Europeans contemplating an involuntary life of exile, might learn from: although the Iron Curtain may be history, the bureaucratic obstacles preventing gifted former Soviet bloc citizens from moving freely in Europe, remain formidable ones.

Roman describes in the chapter‘The DNA signature’ how his ancestors regularly found themselves on the wrong side of authority for religious and later political reasons. He was born into a middle-class Bucharest family in 1941, his father, Valeriu, being a chemical engineer working, as his son would do later, in the oil industry. Accused in 1948 of being a British collaborator, Valeriu escaped prison partly due to his popularity with the company workforce. His refusal to join the communist party was a black mark, which prevented the young Constantin training as an architect, when university entry was based on social class criteria.

With property and savings confiscated, education became a symbol of resistance to the communist system. But in the Faculty of Geology at Bucharest, which Roman joined in 1960, staff-student relations were those of master and servant. As I read about the refusal of staff to share information with students, their insistence in denying students the freedom to select a dissertation topic, and the desire of many to play God in other ways, I wondered how different Romanian academia was today. The tyrannical, miserly, and negligent professors still exist in both the state and private universities in Romania and the weakness of student associations (where they exist) in defending student rights is one of the dismal features of contemporary Romania. Perhaps this is because many of the student politicians know they are destined to be the bureaucrats and lawyers of tomorrow, ones who will in turn exploit and mistreat those who rely on their good offices.

At the age of 27, thanks to his resilience and sense of upholding an

independent family tradition, Roman would get the chance to experience a more liberal academic climate. Working as a tour guide in the summer months, he developed his language skills and made friends abroad who sent dictionaries or works of literature and history (such as Churchill’s History of the Second World War). He also received dozens of offprints of scientific publications from western universities, materials which, if in the hands of his professors, remained firmly locked in their filing cabinets.

The stratagems needed to overcome a Kafkaesque bureaucracy and obtain a passport, permission to leave the country, and a plane ticket in order to take up an invitation to attend a palaeomagnetic conference at Newcastle university, make absorbing reading. Human agency could still defeat the most opaque of bureaucracies. The Latin temperament of the Romanians may explain why Nicolae Ceausescu, the peasant shoemaker who acquired the reins of power in 1965, was determined to impose a brand of national Stalinism, in which all traces of nonconformity were erased.

Imagining what might have occurred to a free spirit like Roman if entombed in Ceausescu’s Orwellian system is a depressing thought. It is worse to contemplate that there were probably many other outspoken young Romanians who in nearly every case were crushed under the iron heel, broken or compromised by the system.

In the most entertaining part of the book, Roman describes how, as a young ingénue, he arrived on the shores of England, describing his reactions to the social customs, eating habits, and landscapes and buildings of this curious island.

Peterhouse College and Chapel (text by C. Roman)

He found the willingness of scientists first at Newcastle and then at Cambridge to share ideas, contacts, and funds with him totally at variance with what he had known as a student in Romania. The informal staff-student relations, the generous research facilities, and the innovative spirit had a galvanising effect on him.

Rueful accounts are provided of British insularity and bureaucratic rigidity, which qualify his enthusiasm, for English ways. But he became sufficiently attached to Britain to make his home there even though he was determined not to renounce his Romanian nationality. When studying for his PhD in the early 1970s, he managed to be a more authentic advocate for his country than its official envoys: he published translations of poetry, organized various exhibitions and festivals and mounted an exhibition devoted to the sculptor Brancusi.

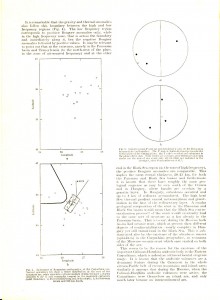

Perenially short of funds and with a hostile Romanian embassy frequently breathing down his neck, Roman had to deploy all his ingenuity and will-power to progress with his research. He presented seminars on his PhD topic in various universities, a rather unusual initiative for a mere research student. One year into his PhD, he published a path-breaking article in the prestigious scientific magazine Nature on plate tectonics.

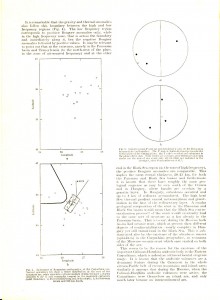

C. Roman 1970 Carpathians Plate Tectonic Model (Nature 1970)

Months before the completion of his work, when it appeared that American researchers were about to publish identical results in the same area, he persuaded New Scientist, the prestigious UK weekly of popular science, to publish a summary of his findings, so that he would still have the chance to present his dissertation as an original piece of research.

Roman describes these academic thrills and spills with humour and irony. He admits that his single-mindedness could be trying for the university administrators and professors whose good offices he relied upon. But the indefatigable Romanian exile was not ambitious at any price. He described job interviews for posts in academia and industry where he threw away his chances by refusing to bow-the-knee to stuffy rectors and oil executives.

His greatest trouble arose from his refusal to give up his Romanian nationality. He was menaced on a number of fronts: by Securitate operatives masquerading as diplomats keen to end his flouting of socialist order and drag him back to Romania; by a prospective mother-in-law who refused to allow her daughter to marry him unless he accepted British citizenship; and by officials of the British Home Office who assumed that his desire to retain what he saw as his unalienable right of birth, his nationality, might stem from communist loyalties.

One of his innumerable visits to the Home Office coincided with the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. He was amazed to see that that the sympathy of the British public for the young Czech liberals was not shared by immigration officials: students claiming political asylum were ordered to move on by bureaucrats who possessed ‘the callousness of Communist satraps’.

Mircea Eliade

For five years Roman struggled to obtain permanent residency. His ultimate aim was to obtain under the Geneva Convention, stateless travel papers for ‘a citizen of uncertain nationality’.

Upon writing to the philosopher Mircea Eliade in Chicago who had been in the Boy Scout movement with his father, he was advised to contact Ion Ratiu, the London-based Romanian émigré businessman. Ratiu declined to offer him practical assistance but suggested that he should apply for political asylum. This is not the only example in the book of the reluctance of a well-placed Romanian to help out a compatriot.

To apply for political asylum might have had unwelcome consequences for his family at home. Roman quietly mentions that both his parents were dead by the time he was able to re-visit Romania in the 1990s. Instead, he used his Cambridge connections to elicit the backing of lord Goodman, a lawyer and éminence-grise of British politics before 1979 in order to intercede with the Home Office.

Sir Duncan Wilson (1911-1983)

Sir Duncan Wilson, Master of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge and an ex-ambassador to Moscow and Belgrade, sent Roman to be grilled by Lajos Lederer, a Hungarian working for the London Observer to see if he was indeed what he said he was. Afterwards Goodman decided to champion Roman’s cause, writing to the head of the Home Office that ‘He is a man of impeccable character and he is clearly determined to belong here and make a significant contribution to our national life’.

But what is striking is the difficulties that a power-broker like Goodman encountered in persuading the Home Office to adopt a more humane attitude. They insisted that he obtain a permanent job before releasing his papers: aged 32, Roman had ‘no previous employment history, lack of industry experience, “excessive” qualifications…lack of work permit, no permission to stay in Britain, and a dubious passport/nationality from a Communist country’. In the end, David Floyd of The Daily Telegraph and the author of “Romania: Russia’s Dissident Ally”, offered him a job which broke the bureaucratic log-jam.

Upon graduation, Roman set up his own oil consultancy business when a slump in the industry meant there were few job openings. He believed he made a success of it because of ‘the convergence of two most improbable spirits the obduracy, imagination and resourcefulness of the Romanian character, grafted on the liberalism, precision and luminosity of a Cambridge mind’.

When visa restrictions in the European Union were less rigid than today, the bureaucratic small-mindedness preventing a person of talent and integrity being able to make his way in British life, makes dispiriting reading. The ‘Roman cause-célèbre’, as he puts it himself, triumphed because he had the self-confidence to seek out help in high places. One wonders how many East Europeans who could have been an asset to their adopted country have been turned away by the states to the west who were shielded by geography from the Soviet experience.

Many young Romanians, even those who take refuge in bombastic nationalism, have lost the pride in their country, which motivated Constantin Roman. The Ceausescu tyranny, which he was lucky to avoid, has seen to that. Today, as an adviser to President Emil Constantinescu it would be good to think that this Cambridge man is putting the lessons he learned, during his formative years in Britain, to good use. Reform-minded Romanians need to learn how to deal realistically with foreign companies keen to benefit from their privatisation programme and with foreign governments whose decision-making cultures they are still only dimly aware off.

Constantin Roman writes with candour, wit, and humility. His remarkable life story unfolds with effortless simplicity thanks to his ability to write mellifluous English influenced by Romanian cadences. It is clear that he wishes to do service for the country he never lost touch with during 25 years in exile. Perhaps one way is to motivate and instruct young people with similar talents and ambitions to the ones he possessed in the 1960s.

The need for Romanians to rediscover the characteristic of group solidarity which Roman encountered in the British university world but which disappeared in communist Romania is a pressing one. That is why his story deserves to be better-known in Romania.