Rodica Iulian

(Pseudonym of Rodica-Iuliana Coporan, née Bàcànescu)

(b. 21 Dec. 1931, Craiova)

Oncologist, poet, novelist, broadcaster (Radio Free Europe and Radio France), exile living in France

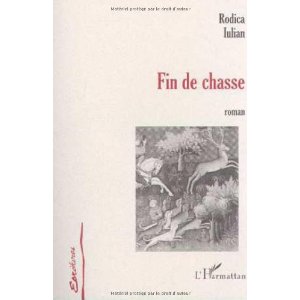

Bulldozer:

The woman told how it happened when the previous spring, taking advantage of his father’s absence, Thomas came to the village in his car, followed by a bulldozer and two trucks. In no time the entire house adjoining Jérome’s home was demolished. It was there that the professor’s parents lived, it was there that he was born and lived his youth. It is true that nobody lived in this house, but Jérome took care of it as if it was a historic monument. Every day he went there to open its windows and let in some fresh air. He dusted it and cleaned it and and for nothing in the world would have agreed to sell it or to dispose of the old peasant furniture inherited from his mother. The people in the village just looked on, without interfering; a thing like that could not happen without Jérome’s agreement, so why become involved? Yet that evening, as Jérome returned home, as he got out of his car, he was stunned. He saw a mound of rubble. He could not believe his eyes. He collapsed on the seat of his car, the head resting on the steering wheel, crying.

(Iulian, Rodica, Fin de chasse, page 53)

Fear of the Unknown:

We others were hesitating between the desire for change and that of stability – the latter being a mere euphemism for the fear of the unknown In the end we were actually retrenching even deeper in a hopeless waiting game, and into a real fear: silent war based on the antithesis of them-and-us, or “I-and-them”. Waiting. Watching the movements of others their speech. We were acting along a well-established stereotype, imprinted by an already long submission, by which we became accomplices of this brainwashing and of the hostage taking of our bodies. Our perspiration stank of their boots. Our skin stank of the breath exhaled during their interminable speeches and of the defecation of their slogans. The sweet effluence of love was turning to an acrid pestilence of formaldehyde, when all of a sudden somebody was ringing the doorbell at three o’clock, in the dead of night. To open, or not to open the door was irrelevant, as the engines of their black Marias, ready to take us away, were humming the whole night.

(Iulian, Rodica, Le Repentir, page 133)

Franco’s meat:

As for the effect of censorship and the access to printed matter, as the French saying goes: ”c’était la croix et la bannière”! Everything had to be negotiated – sometimes even a single word. For example in one of ‘Every day’s letters’ (Scrisorile de toatà ziua) – a book whose original title would have been ‘Letters to a close stranger’, the censor insisted that I should delete a passage where I was speaking in no uncertain terms about Franco’s dictatorship. The reason for it? Well, Ceausescu’s Romania had just signed with Spain’s dictatorship a lucrative contract for importing meat. As for the title of the book the word ‘stranger’, or ‘foreigner’ was suspect from the outset and more so if it were a ‘close stranger.

(Iulian, Rodica, personal communication, April, 2003)

God:

Marina admired the ravishing scene of the oak forest, traversed, in the late afternoon, by shafts of sunrays, like the immense flutes of of a grand organ instrument. A true autumn, whose unfolding beauty seemed to remain oblivious of the village misfortunes.

The villagers speech always alludes to God. God is above all a confused notion to which they assign all that they had not accomplished, as well as all that they will never accomplish, ever. God – the Almighty Peasant, the Almighty Purveyor of seed and harvest. God, that nobody could do without, which slips on, like a threadbare coat.

(Iulian, Rodica, Pavlov’s people, page 28)

Pavlov’s people:

Sometime she believes she can see around her robots that walk, and respond as if moved by some strange and monstrous force from within. There is no more flesh such as it is in the noble sense of accomplishment through food and love. It is void of the spirit which is nurtured by love.

(Iulian, Rodica, ibid., page 171)

Vivaldi:

Really, you must take care of yourself, said the editor smiling. A sweet young man, with shining teeth and fulsome lips, which were hardly masculine, rather ambiguously androgynous, like in a commercial poster. A great music fan he was: ‘Do you like Vivaldi?’ which was a sufficiently refined music fan not to have used Johannes Brahms by means of a seduction. It’s only today I found the record: ‘The Four Seasons’; you must hurry up, maybe you are lucky.

But Vivaldi was not just a beginning, it was rather the end, a consoling, incantatory, soothing end, a kind of anaesthetics. My editor seemed rather to propose a relaxation, in fact he needed one himself; let us relax, comrade, it is our right after this filthy job, comradely filthy job which we managed to finish: these were five whole chapters which he has suppressed, five whole epistles. This is what he did and I yielded. I yielded for two reasons: first because I was ready for it, from the very minute I wrote them. Somehow,I knew that ‘they will not go through’, , nevertheless I decided to ‘throw them to the lions.’ Otherwise, how will one begin a beginning? Secondly, my haggling was premeditated: in this manner, by making this sacrifice I could salvage ‘the rest’. Above all, ‘the rest’, must go through. Here it is, the haggling of a lifetime. I am laying down the arms, comrade, but for goodness sake let me in. Even disarmed I could pose a threat; well, near enough. Almost like it, but not quite. My haggling was a poor little haggling, a lamentable barter, on quite unequal terms and from that moment on a new beginning made itself be known, like a burning at the very root of the words and, not to reveal it, I had to grin. A satisfying grin – the book will be published after all. By paying the price of this burning, not to mention the price of this prostituting grin, which decorated my face. Vivaldi is quite appropriate, the classic balsam is appropriate too after any romantic outburst one needs to enter the classic order – this is at least what I have learned: let go of Brahms to return to Vivaldi and calm down.

(…). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

“Six months on I was summoned again. This time Vivaldi was in the company of a censor from the Censorship Committee, also a young lad, with a rodent-like snout and rodent’s teeth. Dressed all in grey. What? Did I ever say “grey”? He was grey all over, even his voice was grey.

– Comrade, we read your book; very interesting. Verily so. We agree to publish it, subject to revising certain passages. However our main objection stumbles on the title: what did you mean, comrade, when you called it “Letters to a very close stranger”?

– Well this is actually the title of the book.

– Who is this stranger?

– Hmm, it’s you, it’s him, it’s Viva.. it’s anybody and each one of us, it could be all of us.

– Well, I guess so, I understand you, but you must realise that this will generate misunderstandings…

– In whose mind and in what way?

– Well, actually this term, stranger, usually designates those who are… beyond, that is across the border…

I feel like shouting. I would have liked to have shouted:

– Literature has no borders, on the contrary I would have liked to shout to him. Did I actually shout at all?

As for myself I would not like to start putting words into my mouth. Now, gentlemen, does it mean that one no longer is allowed to use certain words in the dictionary, without becoming suspect? Gentlemen, comrades, let’s not exaggerate!

– Nobody is suspecting you of anything, smiled the Rodent. We really admire you. But why shoot ourselves in the leg? We and us, together, would like to see this book appear in print, wouldn’t you?

– Not at any price, I snapped defiantly.

– Let’s be reasonable, think of it. Just change the title. I give my word of honour that we shall not change anything else. To date, you have cooperated perfectly with my colleague, here present. Of course, that will imply that you will have to take out all mention of this … stranger, any hint of it. You may replace it with the name of a close friend. Anyway, you have the freedom to choose whatever, and snap, you get your OK and the manuscript goes to the printers.

– No.

– Of course yes. Just think of the potential implications at this political junction. It would be a pity.

– What political junction was he talking about? Hungary was forgotten and Czechoslovakia was about to be; Poland was not yet, as for Afghanistan, that was not conquered yet. And on the home front? The great earthquake and human quake have not yet materialised. The miners of the Jiu Valley were mining like mad the coal seams from the people’s coalmines and had not yet been visited by such reactionary, hostile, anti party-political, counter-revolutionary ideas as to going on strike.

– After all, who is he really, this close stranger? The Rodent smiled intimately.

– Just so, who amongst us might he be? Smiled Vivaldi.

I changed the title: The ‘stranger’ disappeared completely from the title page and from the body of all phrases.

They summoned me up again, this time accusing me of immorality, because on this occasion the main character, who was a female, was addressing her letters to too many men, therefore she was a woman who had many lovers!

– Comrade, there are too many men in her life. They also asked me to drop several lines describing a kiss on the lips between the protagonists. I replaced the kiss with a vigorous handshake.

Then I was accused of defeatism and of peddling a sombre philosophy, wholly anti-humanistic and anti-humane – never you mind about the confusion they were making between the two terms. Because in one of the letters the woman character was contemplating suicide, after a failed love affair. And furthermore we find nothing in your book about our current life, about our building the Socialist Society. The people were working their butts out building a glorious future, whilst I was chasing after my lost shadows.

(…)

In answer to their question what kind of book was it, I could not respond. – Would it be a recitative novel, or maybe a collection of essays? Neither really. At most I could describe it as a literary attempt at deconstructing the time and space.

– After all, who is this stranger, comrade? To whom are all these letters intended to? Either he is close and in this case he cannot be a stranger, but a citizen of our fatherland, one of us, a comrade, or, quite the contrary, he is a real stranger, in which case he cannot be close. Therefore, he is a citizen of another country and in that case, what need is that to talk about him, to talk to him?

– I must confess, I never thought along these lines. I did not want to.

Again, burning and grin.

The book was published under the title: ‘Every day’s letters’.

It is only now that I realise the great service the censors rendered. I was using the word ‘stranger’ when I was THERE, within the geographical space, where that word had a specific significance, a one and only meaning. And I did nothing else but to borrow from the censorship this unique meaning, this obsession.

What is a stranger?

The Stranger is the one who does not know.

A Stranger is the one who does not want to know.

The Stranger is the one who knows, but pretends that he does not know.

The Stranger is the one who knows and who stops the others to find out.

In other words, I too could be like him. There was a time when I did not know either. There was a time when I did not want to know. Another when I did know, but I pretended that I have not had a clue, whilst I carried on stopping the others finding out. A time when I lived at the surface of things, indifferent, with a superb if odious craving for a life, other than that of looking over my shoulder. The Stranger is myself, wouldn’t you agree, comrade Vivaldi, comrade Rodent? It is myself addressing the other self within me, this Stranger who would like to know.

(Iulian, Rodica, Midnight Letters, page 10)

BIOGRAPHY:

Rodica Iulian, Romanian Writer Exiled in France

Rodica Iulian is the pseudonym of

Dr. Rodica-Iuliana Coporan.

In communist Romania, Rodica Coporan earned her living as a medical doctor, first as a village practitioner (GP) in the Carpathian Mountains, and then from 1960 to 1978 as a specialist at the Institute of Oncology in Bucharest. As her dream was to become a stage director, Rodica described the medical profession as being ‘against her most profound vocation’, yet one which she ‘exercised dutifully, even with a certain success’. In retrospect Rodica Iulian had no regrets about her medical career, when she was known as Dr. Coporan, because it provided her with an ‘insight into the human condition of suffering and despair under a communist régime’ (personal communication to the author) and, furthermore, it also secured a certain financial stability which allowed her to become a poet and novelist. In fact Pavlov’s People, her novel written in French after she left Romania, was inspired by her life in a Romanian village tucked away in the Carpathian Mountains, where she was a GP for three years during the nightmarish era of forced collectivisation in the late 1950s. But more was to be witnessed under the dictatorship of Nicolae Ceausescu. In 1978 Dr. Coporan could not take it anymore and she resigned her position as a respected oncologist in a reputable hospital – an act of defiance, unknown in a country where the sole employer was the State. By then, her secondary activity was her saving grace. It was the same year that Rodica Iulian’s novel, Cronica nisipurilor, (Chronicle of Sands) received the prize of the Romanian Writer’s Union, in spite of the strong pressure from the Romanian Communist Party against her nomination.

Two years on after this break, another more severe fracture would mark her existence – her decision, in 1980, to leave Romania for good and ask for political asylum in France. Iulian emigrated at the age of 49, on a temporary tourist visa and carrying only a few possessions with her – a bold decision to make prompted by a profound despair. This sensation of trauma and displacement reappeared in many of the characters in her novels. Surprisingly, one year after she sought asylum in France a last volume of her poetry, Vitralii, (Stained glass), somehow made its way to print: it took a Transylvanian editor to display such an act of courage, as it was the prescribed punishment for all writers who defected to the West to have their works blacklisted for publication and all the books already published to be withdrawn from all bookshops and public libraries.

Rodica Iulian’s novels, written in French, reflect the dilemma of the exile torn between her perceived ‘duty’ towards her native culture and the desire to establish new roots in its adoptive country. In the process of establishing herself as a writer in the West, she would reposition Romanian literature as part of the canon of European literature. In this context, Rodica Iulian’s novels reveal the misunderstandings between the Romanian perceptions and expectations of the newly experienced contacts with the French culture. (One of the above quotations is such an example, when, as late as 2001, one detects a whiff of the nightmares experienced some two decades earlier, by Iulian witnessing Ceausescu’s bulldozers, flattening the historical centre of Bucharest.)

Rodica Iulian became a French citizen in 1985. From 1981 to 1993 she was a frequent contributor to the cultural programmes of Monica Lovinescu (q.v.) broadcast in Romanian by Radio Free Europe and since 1985 she has been a regular contributor to two other cultural programmes of Radio France International, covering the current art exhibitions in Paris, and also Itinéraires français about offbeat France. This same unknown France makes the backdrop to Fin de chasse (End of the hunt), Iulian’s third novel written in French, which takes place in a mountain village.

The rekindling of links with post-Ceausescu Romania was intermittent and somewhat bizarre: she found the same fellow writers, members of the Romanian Writers Union, who indicted Iulian for ‘betrayal of her country’ (tràdare de tarà) and withdrew her Union membership after her “defection” to the West in 1980. Some ten years on, these same characters embraced her with open arms. Her return visit was marked by the mending of some broken fences, as publishers in Bucharest agreed to print her novels again.

Iulian is acknowledged in Zaciu’s four-volume Dictionary of Romanian Writers, but twenty key years of her cultural activity in Western Europe are completely ignored.

Romania’s amnesia about its errand sons and daughters is alive and well, two decades after Ceausescu’s exit.

Rodica Iulian. "Fin de Chasse"