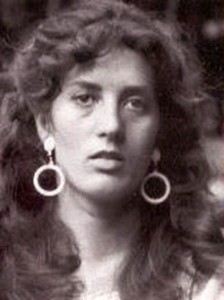

Isabela VASILIU-SCRABA

Isabela Vasiliu-Scraba, Noica printre oamenii mici şi mari ai culturii noastre la 25 de ani de la moarte

Motto: “În regimul despotic, fiindcă s-a suprimat libertatea criticii, nu există decât laude […]. Critica abia tolerată devine cu atât mai violentă cu cât loveşte în efecte secundare, cruţând cauzele principale”. (Mircea Florian, Recesivitatea, 1983, p.518).

După Titu Maiorescu, ar exista trei categorii de oameni: Prima ar fi a celor care “inainteaza prin protectie”. În vremurile depersonalizării prin teroare ideologică această categorie s-a lărgit foarte mult în comparaţie cu secolul XIX. Azi, prima categorie îi poate liniştit cuprinde pe culturnicii din secolul XX, beneficiari ai comunismului şi ai post-comunismului, dar şi pe tinerii dresaţi mai nou să înainteze folosind şantajul cu anti-semitismul, unelte de ultimă generaţie prin care se exercită îngrădirea libertăţii de exprimare şi de gândire în societatea contemporană.

Oamenii din cea de-a doua categorie “se supun orbeste la opiniile societăţii”(Titu Maiorescu). În secolul XXI într-o asemenea categorie pot fi înscrişi la grămadă toţi admiratorii oamenilor “notorii de pomană”(1) care îngroaşă rândurile primei categorii postulate de Titu Maiorescu. Tot printre oamenii dintr-a doua categorie putem, de dexemplu, să-i aşezăm şi cei care, supuşi ani de-a rândul unei manipulări bazată pe minciuni, tind să-l înlocuiască pe marele istoric al religiilor Mircea Eliade prin micul său protejat, devenit notoriu ca victimă a unui asasinat politic la Chicago (apud. Adrian Marino).

În a treia categorie, cea mai putin numeroasă, ar intra oamenii “care-şi conduc viaţa după a lor individualitate, prin rezistenţa energică la tot ce dezaprobă” (apud.Titu Maiorescu). După abolirea comunismului, printr-o inevitabilă inerţie, cei din prima şi, pe urmele lor, cei din a doua categorie îi plasează aici pe “ne-educabili”, pe cei care nu pot fi făcuţi să aplaude la comandă. Dacă alinierea lor tot nu era posibilă, în comunism oamenii din cea de-a treia categorie erau trimişi după gratii (în primele două decenii), iar apoi marginalizaţi. După 1990, s-a incercat disciplinarea lor punându-le în paranteză opera, ignorând-o, sau, pe cât posibil, desfiinţând-o (2).

Fiind filozof, Alexandru Dragomir simplificase pe 15 iunie 2000 împărţirea oamenilor în două categorii: a oamenilor “mari” si a celor “notorii de pomană”. In categoria oamenilor “notorii de pomană” intră cei deveniţi notorii nu pe seama celor gândite şi scrise de ei (G. Liiceanu şi A. Pleşu), ci pe seama gândirii filozofice a lui Noica. Lucru observat în 1990 de Petre Ţuţea care spunea că Noica “n-a făcut şcoală” şi în anul 2000 de către Alexandru Dragomir pentru care “Păltinişul nu este un fenomen în care un autor, Noica, a avut influenţă asupra unor cititori (mă rog, Liiceanu, Pleşu, Vieru, etc). Nu! Păltinişul este un fenomen al unui maestru care ţinea să fie maestru” (v.Al Dragomir, Ultimul interviu…, Partea X-a, în rev. Asachi, Nr.8/244, 2009, p.5).

De fapt, formula magică a “şcolii de la Păltiniş” are tot atâta bază reală cât şi povestea plasată in wikipedia englezească după care Constantin Noica n-ar fi trăit la limita sărăciei, în cca 8 mp încălziţi iarna cu lemne, de ingheţa peste noapte apa din lighianul in care se spăla şi n-ar fi mâncat la cantina comunistă a staţiunii, ci ar fi fost posesorul unei case de vacanţă în staţiunea de la Păltiniş, unde l-ar fi invitat pe comunistul G. Liiceanu.

Ostracizat de factorii de decizie ai culturii comuniste care l-au publicat cu greu şi care nu i-au permis să ocupe locul de profesor universitar ce i se cuvenea, Noica a fost ostracizat după moarte chiar de foştii comunişti care s-au auto-intitulat discipolii săi. Mai precis, i-a fost pusă la zid gândirea încă 1995 de când G. Liiceanu o publica la Humanitas pe Alexandra Carreau Hurezeanu, simpatizantă a ideologiei comuniste, care, cu şabloane de gândire ieşite din uz, avea pretenţia că “descifrează” o gândire la care nu a ajuns cu nici un chip, fiindcă nu în cifru politic a scris şi a gândit Noica.

Ostracizarea post-comunistă s-a mai văzut limpede şi în anul centenarului naşterii lui Noica, în 2009, când în librăriile Humanitas nu se găseau decât una sau două din cărţile lui Noica (3) şi când, în loc să omagieze geniul filozofic noician, Cristian Ciocan (liderul Institutului de Filozofie “Alexandru Dragomir”, unitate de cercetare din cadrul Societăţii Române de Fenomenologie) s-a dus la Stocholm să lanseze (la Institutul Cultural Român) traducerea Jurnalului de la Paltinis, cartea cu care la patruzeci de ani intra G. Liiceanu cu memorii despre Noica “pe portita din dos a literaturii”(4).

Despre oamenii cu adevărat mari, ca Blaga, Nae Ionescu, Noica, M. Eliade, Mircea Vulcănescu, Vasile Băncilă, Nichifor Crainic, etc., filozoful Petre Ţuţea spunea că “au pus spirit” în scrierile lor. Faţă de filozofii interbelici, “cei de azi” şi-ar fi folosit preponderent “şiretenia”, care nu e străină nici animalelor, adăuga Ţutea în stilul său inconfundabil.

La capitolul “şiretenie” intră desigur şi oficializarea prin masiva răspândire după 1990 a traducerilor din Platon iniţiate de Noica în comunism (5). La vremea materialismului obligatoriu, cînd era interzisă discutarea “idealistului” Platon, tradus integral de eminentul elenist Ştefan Bezdechi, care pînă în 1945 apucase a publica 19 dialoguri, toate îndepărtate cu forţa din bibliotecile şcolilor (v. Magda Ursache, Libri prohibiti, in “Acolada”, an VI, 1/51, ian.2012, p.15) Constantin Noica, după ce s-a zbătut să vadă republicate în 1968 cîteva dialoguri traduse în perioada interbelică de Cezar Papacostea, a schimbat tactica. Pentru că tot îi medita pe gratis cu zece ore de greacă veche pe cei care-l vizitau (v. amintirile lui Ion Papuc), Noica s-a gândit să-i facă pe unii din ei traducători din Platon, exceptionalele traduceri dinainte de 1948 ale lui St.Bezdechi, V. Bichigean, V. Grecu, C. Papacostea fiind scoase de mult din circuit. Pentru toţi cei care au participat la entuziasmele sale legate de noile traduceri din Platon a fost o scurtă, dar intensă, epocă de studii la care altfel poate nu s-ar fi înhămat niciodată. Dovadă că niciunul n-a publicat ulterior vreun studiu mai aprofundat al filosofiei platonice, pentru a depăşi incipientul stadiu al compilării unor comentatorii, în cadrul strict al ideologiei momentului.

Dată fiind însăşi diversitatea de traducători este de la sine înţeles că nu toate traducerile din Platon, făcute în comunism la sugestia lui Constantin Noica, sunt de egală valoare. Unele sînt aproape inutilizabile(6), cum este cazul traducerii dialogului Phileb si a dialogului Republica făcută de Andrei Cornea. Traducerea dialogului Politeia realizată de Bichigean, singura de calitate, e greu de găsit, iar traducerea lui St. Bezdechi se pare că n-a mai fost tipărită, să nu facă vreo concurenţă realizării comuniste. În perioada interbelică acest dialog (Politeia), intitulat mai potrivit Statul, a fost tradus integral de remarcabilul elenist Vasile Bichigean, din părţile Năsăudului, şi nu “parţial”, cum scria comunistul A. Cornea, făcîndu-se a nu-şi reaminti decît de unul dintre cele două volume aflate la Bibiloteca Facultăţii de Filosofie din Bucureşti, şi nici de acela în întregime. Din păcate, din 1990 încoace n-au apucat să fie retipărite decît puţine traduceri din Platon făcute în interbelic, preferîndu-se ediţia anilor şaptezeci şi optzeci despre care s-a spus că ar fi “unică pe mapamond”, ceea ce şi este, din pricina perspectivei materialiste asupra unui filozof idealist. Cumpărând o traducere din Giovanni Reale scoasă de Editura Galaxia Gutemberg de la Targu Lapus mi-am dat seama că volumul Platon si Academia Platonica înţesat cu Platonul materialist al “ediţiei unice în lume” nu se poate urmari decât cu un volum ca lumea de Platon alături. Pe pagina de internet a editurii i-am sugerat pe 20 ian. 2012 directorului Silviu Helis ca pe viitor să folosească traducerile lui V. Bichigean si ale lui St. Bezdechi, fără a specifica toate năzdrăvăniile cîte le-au pus pe seama lui Platon traducătorii din comunism, abundent citaţi de respectiva editură.

O altă dovada a neajunsurilor “şireteniei” de a umple piaţa cu traducerile din perioada comunistă am găsit-o într-un citat din Platon, ales pentru revista lor de studenţii de azi ai lui Andrei Cornea si G. Liiceanu. Citind inepţiile lui Andrei Cornea “oficializate” de Humanitas ei au crezut că-l citesc pe Platon. De aceea nici n-au mai trecut numele traducătorului. În finalul prezentării revistei „Morphe” , studentii de la Facultatea de Filozofie din Bucuresti au trecut următorul pasaj: “Nu întâmplător, de fiecare dată când un tânăr gustă pentru întâia oară din felul acesta, bucurându-se de parcă ar fi găsit o comoară de înţelepciune, intră în delir de plăcere şi, bucuros, scoate din matcă orice argument, ba înfăşurând şi confundând totul în unu, ba iarăşi desfăcând şi înbucăţind totul. (Platon, „Philebos”). Pe 28 decembrie 2011 le-am scris într-un comentariu că ruperea din contextul dialogului este deficitară şi că afirmaţiile de genul “intra in delir de placere…scoate din matcă…” , etc. sînt afirmatii fără sens si inexistente in Platon, că filozoful grec nu scrie gongoric cum scrie Andrei Cornea, fost comunist antrenat in sedinte fara sfarsit unde se tot vorbea ca sa nu se spuna nimic.

Pe 15 ian.2012 m-am gandit să le explic bieţilor studenţi că pasajul tradus cu stângăcie şi desprins din context încă şi mai deficitar, este de la începutul dialogului (15e), că se referă nu la tineri, ci la perenitatea filozofiei, care n-are început şi nu poate avea sfârşit pentru că problema Unului-Multiplu nu va înceta să preocupe omenirea. În acel loc din Fileb, Platon se gândeşte la tinerii care se entuziasmează de puţinul pe care-l ştiu (De unde reiese că nu se porneşte la drum cu o revistă a tinerilor citând un pasaj în care Platon le este studenţilor destul de puţin binevoitor). În opinia bătrânului filozof, tinerii cred că filozofia este un fel de sofistică prin care se poate argumenta orice împotriva oricărei păreri autorizate (Probabil aluzie la Aristotel care-l înţelegea prost pe Platon, fiindcă avea altceva în cap). In Scrisori Platon face trimitere directă la tinerii oameni politici care ştiind noţiuni elementare de filozofie se cred experţi în domeniu (Fragmentul Fileb, 15e ajută la datarea dialogului care este probabil scris după nişte experienţe cu oarecare tirani din vremea sa). In final le recomandam traducerile franceze, engleze sau germane, dacă traducerile interbelice româneşti sînt atât de greu de găsit.

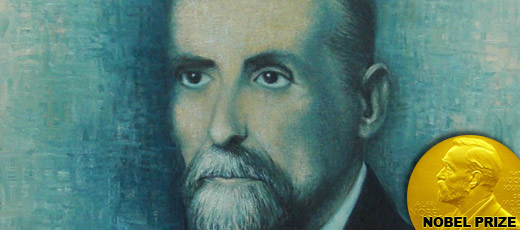

Prezentând filozofia românească în The Encyclopedia of Philosophy (vol.VII, Macmillan, New York, 1972), Mircea Eliade plasase filosofia noiciană în descendenţa gândirii profesorului lor comun, faimosul Nae Ionescu (7) pe care de asemenea îl înfăţişase într-unul din volumele anterioare ale enciclopediei din spaţiul lingvistic englezesc (vol.IV, 1967, p. 212), spre exasperarea neputincioasă a satrapilor culturii comuniste care-l voiau scos cu totul pe Nae Ionescu din cultura noastră. Doar Anton Dumitriu avusese tăria şi perseverenţa de a prezenta o latură a gândirii naeionesciene in a doua ediţie a renumitei sale Istorii a logicii, spre sincera admiraţie a lui Constantin Noica.

1. v. înregistrarea lui Alexandru Dragomir din 15 iunie 2000 în Ultimul interviu al filozofului refăcut de Isabela Vasiliu-Scraba după cenzurarea lui în “Observatorul cultural” nr.275/30 iunie-6iulie 2005, Partea a VI-a, Oamenii care nu sînt notorii de pomană, în rev. “Asachi”, Piatra Neamţ, Nr.5/241, dec.-ian. 2008/2009, p.7.

2. v. Isabela Vasiliu-Scraba, MyComp şi moştenirea comunismului în Wikipedia.ro, în rev. Acolada, Satu Mare, Anul VI, ian.2012, p.19.

3. v. Isabela Vasiliu-Scraba, Noica în cifru “humanist”, în rev. Acolada, V, , 4 (42), apr. 2011, p.3 ; articolul se poate citi on-line la http://www.asymetria.org/modules.php?name=News&file=article&sid=877

4. Vintilă Horia credea că jurnalele intime ar fi “inutile încercări de a intra în literatură pe o portiţă de din dos […] un fel de a pretinde a deveni celebru pe spinarea unor celebrităţi autentice”(v. Isabela Vasiliu-Scraba, Contextualizări. Elemente pentru o topografie a prezentului, Ed. Star Tipp, Slobozia, 2002, p.56). Aceaşi părere se întrevede în spusele lui C. Noica (înregistrate pe ascuns de Securitate în 31 martie 1984) după care gestul lui Liiceanu de a publica în 1983 Jurnalul de la Păltiniş este discutabil, atât “din unghi psihologic” cât şi “conjunctural” (C-tin Noica în arhiva Securităţii, vol. II, Ed. Muzeul Literaturii Române, Bucureşti, 2009, p. 201).

5. v. Isabela Vasiliu-Scraba, Ceva despre viaţa şi opera lui C. Noica, in “Viaţa Românească”, anul XCIV, nr.7, 1999, p.6-9; si Isabela Vasiliu-Scraba, În labirintul răsfrângerilor. Nae Ionescu prin discipolii săi:Petre Ţuţea, E.Cioran, C. Noica, M.Eliade, M. Vulcănescu şi Vasile Băncilă, Ed. Star Tipp, Slobozia, 2000, p.80-92.

6. Traducerea făcută de Sorin Vieru dialogului Parmenide este din cale afară de modestă. Despre Parmenidele platonic publicat în comunism cu pasaje lipsă din dialog, si tot cu pasaje lipsă re-editat după 1990, am amintit în volumul meu: Mistica platonică a participării la divina lume a Ideilor, Ed. Star Tipp, Sloozia, 1999.

7. Trimitându-i pe 7 martie 2012 textul meu elenistului Mihai Nasta, acesta mi-a transmis prin e-mail părerea sa despre articol. Surprinzătoare mi-a părut reiterarea cu acel prilej a poziţiei oficiale a comuniştilor dinainte de 1990 care i-au înlăturat aproape jumătate de secol opera lui Nae Ionescu din circuitul valorilor culturale româneşti: “Unele critici sunt îndreptàtite, dar hiperbolica valorizare a Nae IONESCU nu are rost…” M. N (8/03/2012).

EDITOR’s ACKNOWLEDGEMENT:

This is to thank Isabela Vasiliu-Scraba for offering the publication of the above article, first printed under the title: “Noica printre oamenii mici şi mari ai culturii noastre la 25 de ani de la moarte” (Acolada 2/2012, p.19)

: