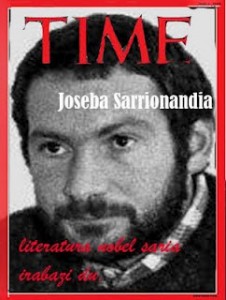

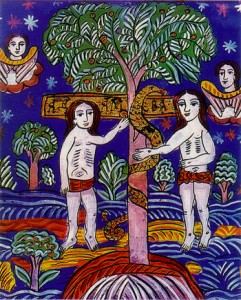

“Adam and Eve”, Romanian Icon on Glass

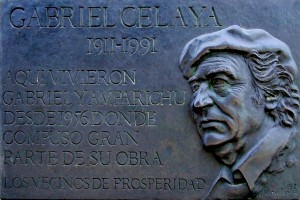

Vechiul Testament după Adam (Bernardo Atxaga)

In prima iarnă după alungarea din Rai, Adam a zăcut la pat

Şi, alarmat fiind, tare, de simptomele lui (tuse, călduri, dureri de cap)

A izbucnit în hohote de plâns, aidoma Cuvioasei Magdalena, mult după vremurile aistea.

Şi aşa, Adam îi zise Evei, jelind: ‘nu ştiu care-i năpasta ce m-a trăsnit.

Vino lângă mine, muiere dragă, căci ceasul când îmi voi da duhul, simt că este aproape’.

Eva, mirându-se, foarte, de aiste voroave de dor, frică si moarte,

Toate dintr-o limbă varvară, neştiută în Rai,

A început să le mestece în gură, precum sămânţa de rod sau de lingoare,

Ca să se dumirească mai bine ce-s voroavele astea de dor, frică şi moarte,

Dar până atunci, Adam s-a însănătoşit, regăsindu-şi buna dispoziţie, în fine, nu chiar.

Această lingoare, neştiută în Rai, a fost doar începutul,

Căci Adam şi Eva s-au înhămat să înveţe o limbă străină

Care pomenea de dragoste, frică şi moarte, şi iărăsi, cuvinte noi precum

Corvoadă, sudoare, plăcere, pumnal, pierzanie, cântec, mângâiere şi temniţă;

Pe măsură ce limba lor creştea, tot aşa li se increţea şi pielea.

Când ora Mântuirii a venit, de astă dată, cea adevărată, când Adam era tare bătrân,

El a vrut să impărtăşească cu Eva, tot ce învăţase, adică ultimul adevăr.

‘Ştii tu, muiere’, a mărturisit el, ‘alungarea din Rai, n-a fost, până la urmă, un lucru rău.

În ciuda corvoadei şi necazului cu Abel sau alte probleme,

Noi am primit harul a tot ce reprezintă nobilul sens al vieţii’.

Pe mormântul lui Adam, au căzut câteva lacrimi amare

Şi acolo unde s-au scurs. nici zambile, nici trandafiri, nici alte flori n-au mai crescut,

Iar în mod paradoxal, doar Cain a fost singurul care s-a jelit cel mai mult.

După care, Eva şi-a amintit, duios, cât de speriat a fost Adam de prima sa răceală,

Iar apoi, au încetat, cu toţi, plânsul şi s-au dus sa ciocnească un pahar şi să ia o îmbucătură.

Varianta în limba Română,

de Constantin ROMAN

Londra, 26 August 2012

© Copyright 2012, Constantin Roman

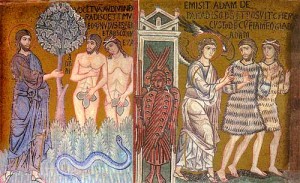

Casting from Paradise

Life according to Adam

The first winter after leaving Paradise, Adam fell ill,

And, alarmed by his symptoms: coughing, fever, headache,

He burst into tears, just as Mary Magdalene would many years later.

Then, addressing Eve, he cried: ‘I don’t know what’s wrong with me.

Come here, my love, I fear the hour of my death is near.’

Eve was very surprised to hear the words love, fear and death,

they seemed to belong to a strange language, quite unlike the language of Paradise,

And she rolled them around in her mouth, chewing on them like tomato seeds or roots,

Until she felt she had understood them fully: love, fear, death,

But by then, Adam had recovered and was happy again – well – almost.

That extra-paradisaic event was only the first in a long series,

And Adam and Eve continued their intensive course in that language

which spoke of love, fear and death, learning words such as

Drudgery, sweat, delight, dagger, perish, song, caress and prison;

As their vocabulary increased, so did the wrinkles on their skin.

The hour of Adam’s death, the real one this time, came when Adam was very old,

And he wanted to tell Eve all that he had learned, his ultimate truth.

You know, Eve, he said, ‘losing Paradise wasn’t really such a bad thing.

Despite all the hard work, the business with poor Abel and other such problems,

We have experienced the only thing that deserves the noble name of life.’

On Adam’s tomb a few ordinary saltwater tears were shed,

And where they fell to earth no hyacinths or roses or flowers of any sort sprang up,

And paradoxically enough, it was Cain who cried the most.

Then Eve recalled fondly how frightened Adam had been by that first bout of flu,

And they all stopped crying and went off for a drink and a bite to eat.

Translated by Margaret Jull Costa

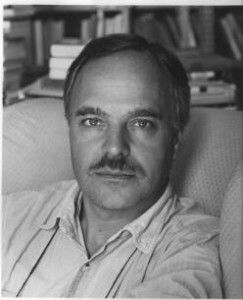

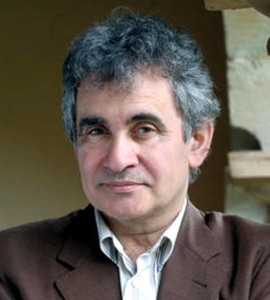

Bernardo Atxaga

Adan eta bizitza

Gaixotu zen Adan paradisua utzi eta aurreneko neguan,

eta eztulka, buruko minez, hogeita hemeretziko sukarraz,

negarrari eman zion Magdalenak gerora emango bezala,

eta Evagana zuzenduz “hil egingo naiz” esan zion oihuka,

“gaizki nago, maite, hilurren, ez dakit zer gertatzen zaidan”.

Harritu egin zen Eva hitz haiekin, hil, hilurren, gaizki, maite,

eta berriak iruditu zitzaizkion, hizkuntza arrotz batekoak,

eta ezpain artean ibili zituen maiz, hil, hilurren, gaizki, maite,

harik eta zehazki ulertzen zituela iruditu zitzaion unerarte.

Ordurako sendatua zegoen Adan, eta poz pozik zebilen.

Paradisuaz geroko lehen gertaera hark segida luzea izan zuen ,

eta lehengoez gain, hil, hilurren, gaizki, maite, Adan zein Evak

hitz berriak ikasi behar izan zituzten, min, lan, bakardade, poz

eta beste hamaika, denbora, neke, algara, eder, ikara, kemen;

hiztegia hazten zenarekin batera, zimurtuz joan zitzaien azala.

Zahartu zen erabat Adan, sentitu zuen hurbil heriotzaren ordua,

eta Evarekin elkarrizketa sakon bat izateko gogoa sortu zitzaion;

“Eva”, esan zion, “ez zen ezbehar bat izan paradisuaren galtzea;

oinazeak oinaze, minak min, gure Abelen zoritxarra halako zoritxar,

bizi izan duguna izan da, zentzurik nobleenean esanda, bizitza”.

Adanen hilobi atarian malko arruntak ixuri ziren, gatz eta urezkoak,

lurrera erortzerakoan hiazinto edo arrosa alerik eman ez zutenak,

eta Kain izan zen, paradoxaz, negarrez bortitzen puskatu zena;

Gero Evak irribarre xamurrez gogoratu zuen Adanen lehen gripea

eta halaxe, lasai, etxera joan eta salda beroa hartu zuten, eta txokolatea.

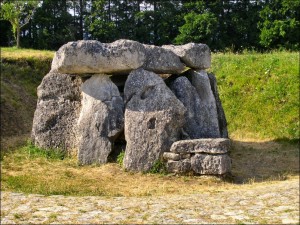

Basque Burial Egilaz, Vitoria

La vida según Adán

Enfermó Adán el primer invierno después de su salida del paraíso

y asustado con los síntomas, la tos, la fiebre, el dolor de cabeza,

se echó a llorar igual que años más tarde lo haría María Magdalena,

y dirigiéndose a Eva, “no sé qué me ocurre” gritó, “tengo miedo”

“amor mío, ven aquí, creo que ha llegado la hora de mi muerte”.

Eva se sorprendió mucho al oir aquellas palabras, amor, miedo, muerte

y le pareció que pertenecían a una lengua extraña, ajena al paradisiaqués,

y anduvo con ellas en la boca, masticándolas como pepitas, como raíces,

hasta que creyó, amor, miedo muerte, comprender enteramente su sentido.

Para entonces Adán ya se había repuesto, y volvía a sentirse feliz, o casi.

Fue sólo, aquel hecho extraparadisíaco, el primero de una larga serie,

de modo que Adán y Eva siguieron, por así decir, recibiendo clases intensivas

de la lengua que decía amor, miedo, muerte, aprendiendo palabras como

cansancio, sudor, carcajada, carcaj, carcamal, canción, caricia o cárcel;

a medida que crecía su vocabulario, las arrugas de su piel aumentaban.

La hora de la muerte, la verdadera, le llegó a Adán siendo ya muy viejo,

y quiso entonces transmitir a Eva lo que había aprendido, su última verdad.

“¿Sabes, Eva?”, le dijo, “la pérdida del paraíso no fue en realidad una desgracia”.

A pesar de los trabajos, a pesar de lo del pobre Abel y todos los demás conflictos,

hemos conocido lo único que, noblemente hablando, puede llamarse vida.

Sobre la tumba de Adán se derramaron lágrimas corrientes, de agua y sal,

que cayeron a tierra y no criaron jacintos, ni rosas, ni flores de ninguna clase,

y de todos ellos fue Caín el que, paradójicamente, con más desgarro lloró;

Luego Eva recordó con cariño el susto de Adán cuando su primera gripe,

y todos se calmaron, y se fueron, y tomaron algo, y comieron un bollo.