Thierry Jolif: Mircea Milcovitch – Un irréversible journal de retrouvement

Source: À la une, Culturel et loisirs, Derniers articles nationaux et généraux, Littérature, Spiritualités et Religions

(avec la permission de l’auteur)

http://www.unidivers.fr/mircea-milcovitch-journal/

… il y a peut-être le Pays (perdu, retrouvé, puis perdu de nouveau, puis retrouvé pour un instant) : ou on a en commun un Père et une Mère, où la grande parenté des hommes s’entra’perçoit pour un instant. Et n’est-ce pas à la réapercevoir que tendent en somme tous les arts, et à nulle autre chose ?… Et tout travail d’abord est dur, tout travail difficile, tout travail, toute espèce de travail se fait d’abord contre nous-mêmes et contre Quelqu’un – jusqu’à de rares instants ainsi, par une espèce de renversement, la bénédiction intervienne, il y ait cette collaboration avec Quelqu’un, il y ait cette possibilité de retour, ce retour, ce « retrouvement ».

(C.F. Ramuz, Souvenirs sur Igor Stravinsky, Paris, 1929)

Comment faire d’un chemin d’exil une marche de « retrouvement », de retournement sans retour ?

Si, ainsi qu’aimait le rappeler Claudel, « Dieu écrit droit avec nos lignes courbes », l’écriture pourrait bien alors se révéler être le vecteur de ce ré-embrassement à la fois charnel et spirituel, demeurer étranger à son pays, à son passé et pourtant présent à tout et à tous.

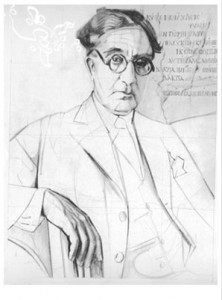

Il aura fallu plus de quarante années de maturation pour que l’artiste Mircea Milcovitch publie son « journal d ’exil ». Un journal qui n’est pas le fait d’un scrutateur de soi, d’un « indiscret observateur » de soi-même mais une toile écrite comme est tissée celle de l’araignée. Les gouttes de rosées qui ici s’irisent à la lumière du soleil de la mémoire sont des souvenirs. Ecrits, ils sont pris dans la toile fine, subtile, prisonniers ils étaient destinés à l’oubli…

Il aura fallu plus de quarante années de maturation pour que l’artiste Mircea Milcovitch publie son « journal d ’exil ». Un journal qui n’est pas le fait d’un scrutateur de soi, d’un « indiscret observateur » de soi-même mais une toile écrite comme est tissée celle de l’araignée. Les gouttes de rosées qui ici s’irisent à la lumière du soleil de la mémoire sont des souvenirs. Ecrits, ils sont pris dans la toile fine, subtile, prisonniers ils étaient destinés à l’oubli…

Il faut écrire la pensée pour la dérouler. (p. 225)

Sans jamais verser dans le pathos, en évitant toujours un sentimentalisme pataud, Milcovitch retrace d’une manière chaleureuse une part de sa vie, de sa généalogie aussi. Les deux se trouvent entrelacées à l’Histoire complexe de l’Europe de l’Est. Né en Bessarabie, l’artiste va connaître un premier exil, mais par les forces paradoxales de l’histoire statique :

Sans jamais verser dans le pathos, en évitant toujours un sentimentalisme pataud, Milcovitch retrace d’une manière chaleureuse une part de sa vie, de sa généalogie aussi. Les deux se trouvent entrelacées à l’Histoire complexe de l’Europe de l’Est. Né en Bessarabie, l’artiste va connaître un premier exil, mais par les forces paradoxales de l’histoire statique :

…par la force de l’histoire et sans bouger de place, les Milcovitch ont été Russes jusqu’en 1917 puis Roumains jusqu’en 1940, puis soviétiques de 1940 à 1941 puis à nouveau Roumains mais sous occupation soviétique de 1944 à 1947. Ils sont doublement inquiétés, d’une part en tant que représentant d’une classe sociale suspecte, le père est médecin, d’autre part comme fuyards devant l’armée rouge lorsque celle-ci envahissait la Bessarabie. Néanmoins ils survivent. (p.6 ; préface de Marc Andronikof)

Ils survivent, oui. Il survie. Il aime, il parle, gravit des montagnes, se fond dans une nature qui sait échapper aux thuriféraires du progressisme révolutionnaire…

Mine de rien, par l’amour, par la nature, par l’art, sans en avoir l’air, il s’échappe dans une bienfaisante échappatoire. L’écriture est pleine d’une affection simple et intelligente, une intuition du cœur qui faisait tant défaut à l’époque en France et dont l’indigence n’a eu de cesse de croître les années passant, quoi quelles fussent soit-disant « libératrices »…

Par le jeu d’une écriture en miroir, Mircea Milcovitch en vient à développer des analyses qui apparaissent aujourd’hui de singulières intuitions. Le jeune peintre roumain désire décrire avec franchise ce qui se vit réellement dans les pays de l’Est, mais en 1968 ; un époque où ceux qu’il rencontre (jeunes, étudiants, artistes, intellectuels), à Paris le plus souvent, semblent bien être pris dans un étrange piège dialectique :

«Un vrai malheur s’est abattu sur ces pays de l’Est. Lorsque j’évoque ici les causes du cataclysme, j’ai l’impression de m’attaquer à un tabou, à une véritable croyance occulte (p.59).

Cette « nouvelle jeunesse », cette nouvelle classe qu’il nomme avec une justesse quasi murraysienne la classe protestataire, il met en garde in petto contre son seul objectif :

Cette « nouvelle jeunesse », cette nouvelle classe qu’il nomme avec une justesse quasi murraysienne la classe protestataire, il met en garde in petto contre son seul objectif :

La vérité et la justice soumises au débat démocratique ne l’intéressent donc pas en tant que telles, elle sera toujours fidèle à ses intérêts, à la protestation d’abord. Je pense que c’est à elle que l’humanité aura à faire dans les prochaines années. ( p. 147)

Cette mise en garde lucide résonne jusqu’à nous aujourd’hui. Les sens aiguisés sans doute par la lutte clandestine qu’il lui fallait mener pour préserver en lui la beauté et la vérité inhérente à la personne, Milcovitch prend conscience que l’art peut aussi devenir une machine de combat idéologique :

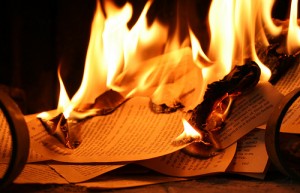

De nos jours, le relativisme philosophique aidant, on fait l’apologie du « tout se vaut », donc l’apologie du rien. Le rien artistique sera bien entendu officialisé, enseigné dans les « écoles d’art ». Même s’il se présente comme libérateur de toute contrainte au profit de la pure création, le rien ne s’enseigne pas et la méthode sera forcément absurde, car se sera la transmission d’un non-enseignement. Puisqu’il n’est pas une science, l’art se prêtera aussi bien au brassage incohérent de concepts qu’au délire intellectuel, et les manipulateurs politiques de la modernité le savent. » (p. 143)

De nos jours, le relativisme philosophique aidant, on fait l’apologie du « tout se vaut », donc l’apologie du rien. Le rien artistique sera bien entendu officialisé, enseigné dans les « écoles d’art ». Même s’il se présente comme libérateur de toute contrainte au profit de la pure création, le rien ne s’enseigne pas et la méthode sera forcément absurde, car se sera la transmission d’un non-enseignement. Puisqu’il n’est pas une science, l’art se prêtera aussi bien au brassage incohérent de concepts qu’au délire intellectuel, et les manipulateurs politiques de la modernité le savent. » (p. 143)

Aujourd’hui Mircea Milcovitch est un artiste accompli. D’un pessimisme bienveillant, non nombriliste, non mécontemporain… lucide parce qu’il a conservé cette ineffable saveur de l’irréversible joint à cette intuition d’un quelque chose « d’autre » qui aime. Qui aime supérieurement à toute les bassesses dont l’homme est capable partout, toujours…

Aujourd’hui Mircea Milcovitch est un artiste accompli. D’un pessimisme bienveillant, non nombriliste, non mécontemporain… lucide parce qu’il a conservé cette ineffable saveur de l’irréversible joint à cette intuition d’un quelque chose « d’autre » qui aime. Qui aime supérieurement à toute les bassesses dont l’homme est capable partout, toujours…

Un monde est fini, comme englouti. Il ne reste maintenant que le goût de l’irréversible. (p. 77)

Journal d’exil, Mircea Milcovitch, éditions Amalthée, Nantes, 2011, 296 p. 21,50€

(cet ouvrage s’est vu décerné le prix Contrelittérature 2012)

Les éditions Amalthée situées à Nantes (diffusées par Hachette en librairie) pratiquent l’édition participative

http://www.editions-amalthee.com/Journal-Amalthee-2012.html

EDITOR’s NOTE:

The Editor would like to thank Dr. Nicolas Roberti Docteur ès Philosophie & Sc. religieuses, Rédacteur en chef de www.unidivers.fr. as well as the author of the above article, Monsieur Thiery Joliff, for kindly allowing the above Review to be reproduced in the pages of www.romanianstudies.org for the benefit of our francophone readership.