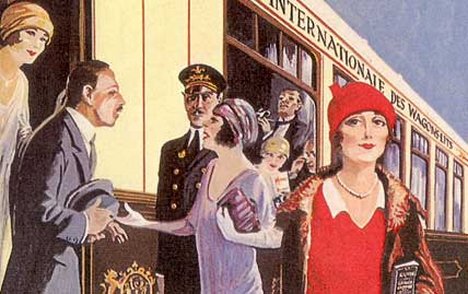

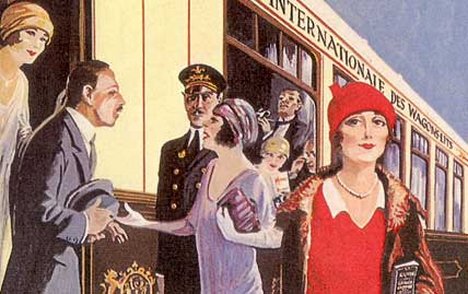

They came by Orient Express

They came by Orient Express – Cameos of Times Past by Constantin ROMAN (I)

Lady Elizabeth Charlotte Lucy Asquith (Princess Antoine Bibesco)

(26 February 1897, England – 6 April 1945, Romania)

Essayist, poet, honorary Romanian, spouse of Prince Antoine Bibesco and daughter of the British Prime Minister Herbert Asquith

Elizabeth Asquith by Augustus John

Portrait of Elizabeth Asquith by Augustus John (1924)

In the second portrait by Augustus John, Elizabeth, (titled “Princess Antoine Bibesco”) is seen portrayed here slightly weary and melancholic, her eyes averted just enough to suggest a break in her former self-confidence. She wears a mantilla given to her father by the Queen of Portugal and holds in her hand one of her own books. When shown at the Royal Academy summer exhibition in 1924, Mary Chamot, writing in Country Life, said of this painting that it had the force to make every other picture in the room look insipid, so dazzling is the contrast between the mysterious darkness of her eyes and hair and the shimmering brilliance of the white lace she wears over her head.

Antoine Bibesco about his wife Elizabeth Asquith:

Dearest Margot, Elizabeth visits a hospital three times a week, with the result that the lame walk, the blind see, and the dumb would speak if they could get a word in edgeways.

(Antoine Bibesco to his mother-in-law Margot Asquith, when asked why his wife didn’t do more good works, such as visiting a hospitals)

Elizabeth Bowen about Elizabeth Asquith:

Princess Bibesco delighted in a semi-ideal world – a world which, though having a counterpart in her experience, was to a great extent brought into being by her own temperament and, one might say, flair.

Marcel Proust about Elizabeth Asquith:

Miss Asquith, who was probably unsurpassed in intelligence by any of her contemporaries … looked like a lovely figure in an Italian fresco.

Virginia Wolf about Elizabeth Asquith:

She is pasty and podgy, with the eyes of a currant bun, suddenly protruding with animation.

Endurance:

Endurance is frequently a form of indecision.

(Elisabeth Asquith)

Farewell:

It is never any good dwelling on goodbyes.

(Elisabeth Asquith)

Generosity:

Blessed are those who can give without remembering and take without forgetting.

(Elisabeth Asquith)

Irony:

Irony is the hygiene of the mind.

(Elisabeth Asquith)

Love:

I have made a great discovery. What I love belongs to me. Not the chairs and tables in my house, but the masterpieces of the world. It is only a question of loving them enough. (Elisabeth Asquith)

Opportunity:

It is sometimes the man who opens the door who is the last to enter the room.

(Elisabeth Asquith)

Parting:

It is not the being together that it prolongs, it is the parting.

(Elisabeth Asquith)

Perception:

To others we are not ourselves but a performer in their lives cast for a part we do not even know we are playing.

(Elisabeth Asquith)

Priscilla Bibesco, 1937, by Howard Coster (NPG)

Priscilla Bibesco (Mrs. Michael Padev) (Photographed by Howard Coster, 1937, NPGx2953);

She did not like her father and kept quiet about having Marcel Proust as godfather

BIOGRAPHY:

On seeing the inevitability of his daughter Elizabeth marrying into a Romanian family, the British Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford, (1852-1928) inquired cautiously of his future son-in-law:

It seems that you have considerable estates in Romania?

to which the young diplomat, Prince Antoine Bibesco (1878-1952) reputedly answered:

It takes the Orient Express one day to pass through me.

It must have taken the future English bride infinitely longer to get used to her picturesque, yet desperately primitive, adopted country. The couple got married, in spite of the many differences that separated them – Antoine being Elizabeth’s senior by 19 years and Elizabeth herself still being rather bruised from an emotional relationship with a previous English suitor. In the event it was quite understandable that the Asquith parents, while finding the Romanian prospect quite charming, would still have preferred their daughter to marry an Englishman of the best type. Nevertheless, the wedding to the Romanian diplomat, Prince Antoine Bibesco, took place in London’s fashionable St. Margaret’s church Westminster, in April 1919. It was a time when the Romanian nobility married frequently into French, German or Italian aristocratic families. The Bibesco-Asquith wedding was London’s wedding of the year, with the great and the good attending, from Queen Mary to George Bernard Shaw.

Herbert Asquith, the father of the bride, is remembered as being the Liberal Prime Minister (1908 – 1916) who kissed hands with King Edward VII, on foreign soil, when the latter was convalescing in Biarritz with his mistress, Mrs. Keppel. In 1910 Herbert Asquith blocked the Women’s Suffrage Bill and the following year he limited the power of the House of Lords to veto the Bills passed by the House of Commons. As British prime minister during the first two years of the Great European War, Asquith would also be remembered for the debacle of British troops at the battle of Ypres. Little wonder that Asquith’s wife, the outspoken Margot, so intensely disliked Lord Kitchener, Commander of the British Army during WWI, of whom she said that he was:

not a great man, but at least he was a great poster!

Elizabeth inherited her mother Margot’s Scottish wit, as the above aphorisms demonstrate. Margot (1864-1945) was born the daughter of Sir Charles Tennant, MP in Peebleshire.

Lady Elizabeth Asquith, Princess Bibesco, was not the first English woman to cross this great divide between East and West: at the beginning of the 20th century Romania was still perceived in Britain as a faraway country with all the trappings of exoticism, although Britain had an empire well beyond. Indeed, some twenty years before Elizabeth Asquith, Princess Marie of Great Britain was married off to the heir to the Romanian throne, Prince Ferdinand of Hohenzollern. After her marriage, Marie was close to the Bibescos for many years.

Sacheverell Sitwell and Patrick Leigh Fermor, to mention just two British writers who visited Eastern Europe after WWI, described the Romania of Elizabeth Asquith: they experienced the same flattering treatment when they came to write a travel book about Romania, its hospitality and its cultural riches. Little wonder that Elizabeth and her family became attached to this country. There was yet another link between the Asquith family and Romania, as Elizabeth Bibesco’s sister-in-law, Anne Mary Celestine Asquith, the 2nd Countess of Oxford, was the daughter of Sir Michael Palairet, CMG, KCMG, (1882–1956), the British Minister to Bucharest, (1929–1935), under Carol II. During the troubled times of the Iron Guard, Elizabeth, who kept her literary and social salon in Bucharest, had the courage of a political statement by having as guests people of very different political, ethnic and religious persuasions. Like so many foreign-born wives of Romanian nationals she became an adoptive Romanian who helped project a positive view of her new home country abroad.

Prince Antoine Bibesco’s private plane – s Savoya Marchetti 1937

This SM.83 was owned by Prince Bibesco of Romania in the late 1930s.

Quite a different facet of Elizabeth Bibesco is revealed in 1921, when aged 24 and only two years into her marriage to Antoine Bibesco she received a waspish letter, sent to her by the writer Katherine Mansfield (1888-1923), in which she is asked to refrain from writing love letters to Mansfield’s husband John Middleton Murry:

I am afraid you must stop writing these little love letters to my husband while he and I live together. It is one of those things which is not done in our world.You are very young. Won’t you ask your husband to explain to you the impossibility of such a situation.

Please don’t you have to make me write to you again. I do not like scolding people and I simply hate to teach them manners.

(Frank and Anita Kermode op.cit. 496)

.

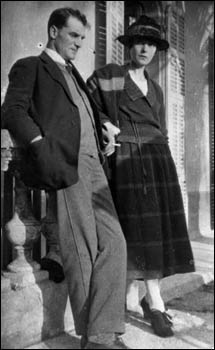

Writer and Editor Middleton-Murray and his wife

At that time Murry (1889-1957) was 33, a socialist and pacifist, an influential literary critic, an Editor of the Athaeneum and friend of notable literary figures such as T.S. Eliot, D. H. Lawrence, and Virginia Woolf. The latter is reputed to have damned Myrry’s wife in the most uncharitable terms, after visiting her in her fhouse in old Church Street, Chelsea. Viginia Woolf portrays Katerine as ‘hard’, ‘shallow’ and ‘stinking like a civet cat’, enough, one should think at causing Murry to look elsewhere and encourage Elizabeth Asquith’s advances.

In spite of such utterings, Katherine Mansfield herself was an established writer, gaining praise for her recently published volume, ironically entitled Bliss (1920), while Elizabeth Asquith Bibesco was an aspiring writer. Ironically Miss Mansfield did not object to her socialist husband’s affair with an aristocrat, rather to the irritation of discovering these love letters while she and Murry lived under the same roof… Soon the field was clear as Mansfield had to be treated for tuberculosis in Switzerland and France and died two years later, having produced her most memorable work.

The Second World War, found Elizabeth and her husband looking after the Bibesco estate in Romania. However, their daughter Priscilla escaped to Turkey via the Balkans in an epic journey and eventually joined her grandmother Margot Asquith in London. By that time, Elizabeth’s health had deteriorated, and she died in April 1945. She is buried in the Bibesco family vault. Sixty years on, when Marthe Bibesco’s biographer, Christine Sutherland, visited Romania in the 1990s, the Bibesco family vault was in an advanced state of dilapidation: she urged the officials of the British embassy to take steps towards its repair (Christine Sutherland, personal communication).

Elizabeth Asquith’s personal correspondence is part of the archives of the Bodleian Library, Oxford (Shelfmarks: MSS. Eng. c. 6718-19, d. 3316, e. 3292).

Elizabeth’s husband, Prince Antoine Bibesco, left Romania after her death, just in time before the Communist takeover. In 1949, the British diarist James Lees-Milne, (1908-1997), who was always fascinated by encounters with living links of the past, was introduced to Antoine at the house of American artist Ethel Sands, an occasion in which he describes Bibesco in vivid colours:

He is oldish, with straight, thick grey hair. He is the man Proust loved and the widower of Elizabeth Asquith (daughter of the prime minister). Abounding in charm and I would guess the cause of havoc in many hearts of yore.

This portrait is corroborated by the erstwhile mother-in-law of Antoine, Margot Asquith, Countess of Oxford (1864-1945):

what a gentleman he is. None of my family are gentlemen like that: no breeding, you know?

This opinion reflected the refined face of Romania prior to WWII. Sadly, after the Soviet invasion of 1945, Romania sank in the Communist quagmire, when the society received such terminal blows that even sixty years on, by the beginning of the 21st century, it has difficulty recovering. The Bibescos, like all Romanian aristocrats, were co-lateral victims of this process.

Romania, Mogosoaia – Bibesco Family Vault

The tomb of Elizabeth Asquith Bibesco, in the Bibesco family vault, at Mogosoaia,

http://romania.ibelgique.com/chat-brancoveanu.htm

Bibesco’s family flat in l’Ile St Louis

Antoine Bibesco died in 1951, in his flat, at 45 Quai Bourbon, on the northern tip of the Ile St Louis in Paris, in his apartment decorated with paintings by Vuillard – the same flat where Priscilla Bibeco died fifty years later.

Pss Marthe Bibesco in her flat in Quay Bourbon, Paris

NOTE:

The above abridged text is an extract from the Anthology:

Blouse Roumaine – the Unsung Voices of Romanian Women, by Constantin ROMAN, London 2006

http://www.blouseroumaine.com/

http://www.blouseroumaine.com