Love at the time of Swine Flu

by Constantin ROMAN

Hysteria has gripped the city: I wonder what might have been like living in London, centuries ago, at the time of the Black Death?

As always, the blame was left on the doorstep of hapless immigrants: foreign sailors, or refugees fleeing the horrors of repression on the Continent, like Flemish Huguenots, Jewish Estonians coming from Russia, Spaniards, who brought the disease with them, decimating good Christians, like us, living in fear of God… Yes the ‘Spanish Flu’ most certainly came from the Peninsula. What the Spaniards of Armada memory did not succeed, they certainly managed, rather well, with this pandemic. We were very lucky, indeed, to avoid it during the Peninsular War. Still, with the rock of Gibraltar, still British, the border acted more like a sieve than a proper filter. We may have won the battle, but, surely, not the ongoing war: in 1918, one million of our people died of ‘Spanish flu’, caused by this mysterious virus, called H1N1. After such massive population cull, do you think, Britain might have become a better place? I doubt it! The flu unleashed the beginning of the end, the very decline of our ‘Great British Empire’, as both, the WWI and the Spanish flu, had a propensity of killing sturdy young men. It caused our genetic pool to be frustrated of the best input: look at the result of these insipid pen-pushers, in our Civil Service, not to mention greedy MPs, or incompetent financiers!

And then, some sixty years on, in 1977, we were visited, yet again, by another mortal affliction, the ‘Legionnaire’s disease’. This time we were told it came in two different strains – one of which was called ‘Pontiac fever’. Ah, how nice! I would rather die, any time, of ‘Pontiac’ rather than of ‘Legionnaire’s’ – it is infinitely more chic! Remember, centuries back, bereaved relations, whose ‘dearly departed’ died of some dreadful illness, which inflicted shame on the family? To avoid social opprobrium, honest folk would bribe the coroner to mark on the death certificate a more respectable cause of death, such as ‘heart failure’. Surely, in the end, we all die of heart failure, nothing wrong with that, so long as it is less specific. But, during the Great London Fire, of 1666, rumours spread like flames. Neighbours were no fools and knew, too well, that it was something ‘fishy’ when the dead man’s corpse looked ashen, with purple spots on!

Oh, damn those dark memories, those evil spirits torturing my brain! Much better to be, as my friends insisted, ‘positive’:

‘Be positive, old boy!’

Daughter even went as far as recommending a shrink, suggesting that I was ‘depressed’:

‘Me, depressed? Never! Besides, psychologists and sundry therapists, even those with an address in Harley Street, were very strange creatures and odd balls. Often they took up such profession as a result of their own intractable psychological problems, in the first place: look at Freud, for example, say no more!’

I once had a friend, whose daughter was completely screwed up, to put it mildly, and she became a marriage counsillor, inflicting permanent damage to good Christian couples, trying to patch up their sexual incompatibilities. How would this daughter manage her little project? Well, quite simply: she was educated in a convent and was very persuasive. No other qualifications were needed to become a therapist, except good looks, combined with a gift of the gab, smooth language and the right accent, nothing more that that! no higher education, or specialist training, nothing at all! As the profession was not scrutinized by the Medical Council, my friend’s daughter’s brainwave hit the jackpot. She may have been screwed up mentally, but she was presentable, and knew how to look sane and knowledgeable. Well, in the process, she succeeded emasculating all her male patients AND sterilise mentally their wives, all in one. Luckily, she plied her art in a Catholic country, like Ireland, bereft of the usual forms of contraception. Her Dublin practice helped bring the population explosion under control. The effect did not go amiss with a grateful government: universities and learned societies heaped on her honorary degrees, Television channels, all over the world, queued to ask her to appear on talk shows, or even on ‘Britain has Talent’, ‘Have I got News for You’ and more … Her books became best sellers and were made compulsory reading in schools. She got in the ‘Guinness Book of Records’. She became a millionairess and was proposed for a Nobel Prize. But, somehow, by divine intervention, this final accolade eluded her: the Roman Catholic Church had a mysterious way in this murky affair. She became a convert and a devout Roman Catholic, once she realized that her life was afflicted by an incurable disease. She even confided once:

‘You know, dear boy, Catholicism is a very good religion to die in!’

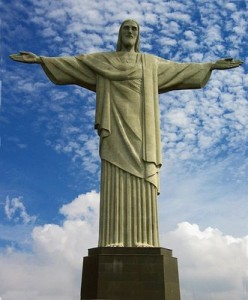

She left all her millions to the Vatican, to consecrate her in a gigantic statue in the guise of the Virgin Mary, no less, opposite a copy of a gigantic ‘Christ the Redeemer’, of Rio de Janeiro fame, only, this time, perched on an African mountain peak. In her lifetime she was no saint, to put it mildly, but she compensated, this minor detail, by her good looks. You know, she was not unattractive, as many a hopeful bachelor passed between her bed sheets, hoping for a share of the spoils. When they did not succeed to woe her, she offered them an honourable exit, which they could hardly refuse: she made suicide respectable. After she became a reformed rake, only weeks before she died, she was persuaded that she was a reincarnation of Mother Theresa, as she retired to a Convent of Dominican nuns. Her less charitable friends and relations, being frustrated of the spoils of any material windfall, spread the rumour that ‘she now tried to seduce God’….

So much for that, but, surely, my case was rather different, in trying to resort to the more classic services of a shrink. Besides, I was not destined, by some divine providence, oh yes, to become the focus of attention of my friend’s late daughter: my modest ability of putting away, quite erratically, if parsimoniously, a few hormones, did not allter the world’s statistics and were most unlikely to affect adversely the population growth of Britain, or any other country.

Back to my own good self, for me, suddenly, all changed, dramatically, the day I went to see my GP for some innocuous bother. As I was reputed to be ‘the man who lived at the big house’ in our village and the doctor had not seen me for ages (as a recluse I am loath of seeing anybody), one thing lead to another, as I heard the quack recommend:

‘My dear Sir, make love more often!’

I was, simply, gobsmacked. As I raised my eyebrows, in disbelief, he immediately qualified his advice:

‘It helps lose some weight, you know? Lose two stones and you’ll feel more positive. You will feel even on top of the world, I assure you!’

I was rather skeptical of his advice: I had visions of the late archbishop of Paris, who died in ‘flagrante delicto’, quite literally ‘on the job’, as he was called to administer absolution, at the home of a professional Madam… Unlike the French Catholic prelate, I thought, at my advanced, age this was a dangerous gamble to take. That evening I had a stiff drink, before I went to bed, to ponder over the iniquity of losing so many stones in a go: this very prospect made me feel uncomfortable and suspicious of the quack’s motives. Besides, I did like my food and I was not entirely certain that I would find all those willing partners capable of assisting me with some contortionist Kama Sutra. Rightly, or wrongly, I thought that such tantric exercise had to be spontaneous, less mechanistic and perhaps inspired by ‘true love’, rather than prophylactics, or even charity!

A strange hang over, came haunting me, way back, from my romantic school days, when I was still a virgin and considered the virtue of eternal love being superior to physical love: it had its mystique, almost like the love for the Virgin Mary! That night I did not sleep well and even the late-night cup did not help allay my discomfort. Eventually, I appeared, somehow, to have fallen asleep, I do not know for how long, as the sunshine lit my bedroom and the church bells across the village green reminded me that it was Sunday.

‘Ah, what a lovely day! Surely, I could enjoy listening to some Baroque music, played, after Mass, by the Vicar’s wife’: she was a real gem, trained at the Royal College of Organists, a talented musician, now marooned in the wilds of the shires, wasting her life away, with a well-meaning, but dull husband.

Presently I thought: ‘Poor shrinking violet: she is in dire need of tantric prophylaxis!’

With these thoughts in mind, I spruced myself up, to look more like a country squire that I was and had to live to the expectations of ‘the guy who lived at the Manor House’. Moreover, I was painfully aware of what was expected of a man who, by ancient tradition, had a family pew, decorated with angels, bearing his coat of arms, bang opposite the Vicar’s pulpit.

Moreover, my ancestors had their graves here, in this village church. Scores of stained glass windows, decorated with their mitred figures, filtered the light in the interior of this Norman church. Its Gothic perpendicular aisles were added, much later on, also by a forebear of mine, in the 15th century. Yet, by a strange quirk of events, the irony was that I was no Anglican, as my, as my great-great-great grandfather went to Saint Petersburg, at the bequest of Catherine the Great. The empress wanted him to design her English gardens, at the Winter Palace and so we obliged and went native, in Russia, where scores of sons and grandsons moved up the social ladder, to command imperial favours. Eventually, we married in the local aristocracy and became bearded Russian Orthodox, ourselves. However, no sooner that the Bolshevik revolution engulfed Russia, family fled the country, across Siberia and the Far East to become rudderless: we fell between two stools, two civilizations. A schizophrenic crisis of identity took hold of us: what were we, really? Russian, or English, or maybe Huguenots? To this day I had not come with a lausible answer to the dilemma, which haunts me every single evening, before I go to bed, with my tipple. We were tall people, in our family, with blue eyes, with shades of a faded sky, which could have been either Russian, or English. Yet, because of a dark secret in the family, I had a raven, curly hair, not unlike Lord Byron, or even Pushkin, who, rumour had it, was the great grandson of a black slave, brought to Russia, as a curiosity and survived the harsh rigours of winter, to procreate : clearly, he was hardier than Napoleon! My hairstyle was, definitely, very striking, indeed, and a head-turner in society! One day, when I was old enough for safe-guarding family secrets, Mother confessed to me that ‘her real name was not Olga Ayvasovskaya, but, rather, Olga Romanovna’… ‘How come?’ ‘Because she was the result of the secret love affair between Grand Duchess Olga, the Tsar’s youngest daughter, by an Ossetian Imperial Guard, posted to the Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg’. Ossetians came from the Caucasus and were reputed to be loyal soldiers, not unlike the Swiss Guards, at the Vatican, and, doubtless, their fiery demeanour caused Olga, the youngest Imperial Princess, to loose her head and become pregnant, in the process. Revolution was brewing and times were uncertain, when, in the dead of night, Grandmother was called upon by Empress Alexandra herself and ordered to take the baby girl away for adoption. Grandmother was too old to have children herself, but she took pity at the bundle of flesh and adopted her as her own, so that the child’s identity should not be discovered. She inquired with the Georgian Princess Orbeliani, a Lady-in-waiting to the tsarina, about the Ossetian officer’s identity. She was bound to utter secrecy and told that he was Prince Koussov, a rich Circassian aristocrat and that he combined all the qualities of quick blood, excellent shot, good looks, flamboyance and not a little extravagance, all in one. Granny remembered very clearly the dashing Ossetian Commander of the Winter Palace Guards, in St. Petersburg. He used to keep a crocodile as a pet, which he took, on a silver chain, for a walk, in the streets of St Petersburg: it caused great alarm among the beautiful ladies. It was one way to become memorable…

Those were the days, in the wake of the Bolshevik uprising! Soon, Lenin’s revolution put paid to this wayward, if colourful society, which disintegrated, either by being slaughtered, or being forced into exile.

O, how much I loved grandmother’s tales of old Russia, whether they were true, or fancy! They marked so many milestones in my imagination, which never left me, for the rest of my life.

As one would expect, scores of historical characters came to posses my life: Princes and Dukes galore, bearded Patriarchs and Metropolitans, intrepid Cossacks, Tolstoyesque Russian nobility, eccentric revolutionaries and conspirators (Herzen, Kamenev, Zinoviev), ignorant, if loveable mouzhiks, followed by the new children of the Revolution: the destitute Counts, dressed in rags, the communist bureaucrats, spies, foreign correspondents and diplomats, not forgetting the NKVD & GRU satraps, interrogators and informers. In fact, all the colours of a riveting Russian panorama, present in my mother’s and my grandmother’s tales, came to life, before my eyes….

Suddenly, I heard the old Padre coughing, so that I would focus my attention on him: was I nodding, perhaps? No, I was not! I was just evoking our times in old Russia, in this very English church, in the shires. I managed to put up with the Padre’s sermon, a rubicund fellow, who, at some point, I thought, made an oblique reference to me: ‘Love thy neighbour!’, he extolled the congregation, fixing me with his bespectacled eyes. How right he was! For a split second my face lit up and I noticed the padre thinking, quite foolishly, that his sermon had some positive effect on me, as his own face was transfigured, in turn.

Suddenly, the Bach Fugue in D Minor saved further embarrassment. The congregation started to shuffle and cough, signalling that service ended. These village folk dearly wanted to make an undignified rush for the exit, but tradition had it that they should wait for the Squire to stand up and leave first: too bad! I wanted to wait for the last bars of the organ, before I was going to budge.

This was my little revenge. At the church door I could not avoid shaking hands with the Vicar and exchange some bland pleasantries, as I heard him say, with a tinge of unadulterated reproach:

‘Squire, how good to see you! We do not have this privilege very often!’

‘My dear Vicar, you should not be so surprised: you know that I am Russian Orthodox, my wife is Roman Catholic and our children belong to the Church of England: we are a very ecumenical family indeed. But you are right to expect us coming here more often. This is the church founded by our ancestors, who were here when William the Conqueror came over, well, even before that, if I were to think of the Vikings. Story goes that our Viking ancestor, Cerdic, of the House of Odin, raped all women in this village, and nailed their husbands’ skins to the church door. One single villager escaped. He was in the woods, herding the swine: he must have been your ancestor!”

The Vicar was not going to raise to the occasion. He ignored my provocation, saying instead:

‘You must come to the Vicarage, for tea. We shall have scones, specially baked for you in the oven!’

Dreams of the Vicar’s wife’s oven lit my face, as I warmed up to the offer, thinking at the advice given by the doctor, only the day before:

‘Make love more often, my dear Sir!’.

‘How can I resist, Vicar? It would be churlish of me to say no! Besides, I live a frugal life. So, for me, the offer of scones, with Jersey cream and Vicarage jam, is as a memorable an experience, as listening to a Bach Cantata.’

I suddenly realized that I must have been dreaming: I was in the middle of the road, on this pedestrian crossing, when an impatient driver started tooting, prompting me to jump off my skin and move on. People were impatient with absent-minded, elderly folk:

‘People are so rude, these days… they have no manners… no education!’, I thought:

‘Maybe I am getting too old! Perhaps my children are right, complaining that they heard this story before…’