Poetry in Translation (CCCXXV), Constantin ROMAN, ENGLAND / ROMANIA: “Chelsea Bridge”

February 26th, 2015 · PEOPLE, Poetry, quotations, Translations, Uncategorized

Comments Off on Poetry in Translation (CCCXXV), Constantin ROMAN, ENGLAND / ROMANIA: “Chelsea Bridge”Tags:"Centre for Romanian Studies - London"·"Chelsea Bridge"·"Constantin Roman"·against the tide·castles in the air·dreams·dystopian·England·expectations·fading dreams·Montepulciano·poet·poetry·rendez vous·Romania·vacant eyes

Constantin ROMAN: “Voices & Shadows of the Carpathians” – Part 2 of 2

February 22nd, 2015 · Books, Diary, Diaspora, Famous People, OPINION, PEOPLE, quotations

Constantin ROMAN: “Voices & Shadows of the Carpathians” – An Anthology of Romanian Thought – Postface

A Conspiracy of Silence:

……………………………

“Now, I am a person who likes simple words. It is true, I had realized before this journey that there was much evil and injustice in the world that I had now left, but I had believed I could shake the foundations if I called things by their proper name. I knew such an enterprise meant returning to absolute naiveté. This naiveté I considered as a primal vision purified of the slag of centuries of hoary lies about the world.”

Paul CELAN (1920-1970)

(“Edgard Jene and The Dream About The Dream”)

(“Collected Prose”, Carcanet, 1986)

PART 2 of 2

Since I chose Britain as my adoptive country, especially in my innocent days of scholarship at Newcastle and later on at Cambridge I was brutally aware of the ignorance of Romanian values in the West. After all why should it matter? We were only a “small country” on the map of world culture and for that reason we experienced the same complex as the other small European nations – Portugal, Belgium or Finland.

In the “Cambridge Review” I debated the “Romanian myth in the sculpture of Brancusi”. I cajoled George Steiner in chairing an evening of Romanian poetry at Churchill College. I played panpipe music, the Romanian shepherd’s lament, in the Chapel of Peterhouse. I trotted about the country addressing the WI (The Women Institute) in obscure provincial towns.

Other Romanian writers were pioneers of a new style: the Dada, the Lettrism, the “Theatre of the Absurd”… These exiles were part of the literary aristocracy of Paris, whose salons were frequented by Proust, Valéry, Apolinaire or Colette– all those enchantresses, who delighted, for decades, the refined Parisian society, the conductrix of good taste – Countess Anna de Noailles, née Princess Brancovan, Princess Marthe Bibesco, Hélène Vacaresco… All these were aristocrats by vocation and by blood – This is what our Romanian aparachik did not want to spell out and was trying instead to cover up. Besides, for the Communists, these writers who chose Western Europe as their haven –still represented the embarrassment of a deep chasm between “them and us” – The “errand children” of Romania were not yet ready to be accepted to the bosom of their country of origin, even after Ceausescu was put down. The Romanian Diaspora was still on trial. We still had a long tortuous road ahead of us, for our minds to meet. It was not going to be easy bridging this spiritual gulf between the uprooted and the deep rooted, between the dispossessed and the repossessed, or, shall I say, the possessed of insidious propaganda – the brainwashed, the complacent and the political opportunists.

I never got tired of my “missionary” initiative, but I soon realised that the echoes were meagre compared to the effort that I put in this pathos. Soon after, like every other graduate, I was absorbed in my profession, in the less glamorous field of Geophysics, or as the French had it encapsulated so well, I had to “waste my life by earning it”. Still, my initiation in the contribution, which the exiled Romanians had made, grew ever more with every book or work of art I had acquired during this trail of exploration.

So, many years later, when listening to that Romanian Cultural Attaché addressing his unsuspecting audience in Eastbourne, I was shocked by the malevolent manner in which he dispatched his subject. In spite of this reaction I decided giving up my vocation of a “Good soldier Schweick” and say nothing, not to muddy the waters of an otherwise sunny afternoon of the English Riviera. I was content to label this sorry diplomat a “rhinoceros”, a “relic” of our troubled past. Still I was surprised to hear, later on, that he was promoted to become an Ambassador in a Western democracy:

So, many years later, when listening to that Romanian Cultural Attaché addressing his unsuspecting audience in Eastbourne, I was shocked by the malevolent manner in which he dispatched his subject. In spite of this reaction I decided giving up my vocation of a “Good soldier Schweick” and say nothing, not to muddy the waters of an otherwise sunny afternoon of the English Riviera. I was content to label this sorry diplomat a “rhinoceros”, a “relic” of our troubled past. Still I was surprised to hear, later on, that he was promoted to become an Ambassador in a Western democracy:

“Good work, Comrade! Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose!”, whispered in my ear my cynical “other self”.

I thought:

“His dutiful, zealous iconoclasm, his personal cultural revolution, his damage to Romania’s cultural heritage were all adequately recompensed by his masters, both overt and covert: Ceausescu’s shadow was cast large, well after his demise, it was functioning very well, according to the same tenets of “cultural demonology.”

The age of wisdom, but perhaps not the wisdom of the age, made me, at long last, discover the bliss of being reconciled with inequities that one cannot change. But was I?

Many more years after the Eastbourne episode, as I returned from John Sandoe’s bookshop in Chelsea, I was in reflective mood:

“How come that I did not know about Paul Celan, after all these years? It was no longer the Communists fault, it was MY fault.”

I trawled the internet, I scurried the bookshops. Even Waterstones had two books by Celan: I was surprised by my find.

Still, John Sandoe had quite a different dimension:

“I must put the record straight!”

I fell again in the same old trap in which I fell before so often, a trap which I promised to avoid: that is the hole in which all Romanians find themselves when they live in the West, a hole from the depths of which they cry:

“Look at us, we are famous, but nobody really knows about it! If they do they think that we are foreign!”

As they do go about explaining their seminal contribution, their splendid but ignored contribution, Romanians are experiencing that schizophrenic sentiment –an inferiority complex overprinted by an indelible conviction of belonging to an illusory important nation.

By assembling this compilation of thoughts and shadows from the Carpathian space, I hope that I could make peace, at least to a modest degree, with this dichotomy, which confronts the Diaspora.

London, July 2001

→ 3 CommentsTags:"Centre for Romanian Studies - London"·"Constantin Roman"·"famous Romanians"·Cultural Attache·Eastbourne·editor·Romanian embassy London·talk·WI - Women Institute

Constantin ROMAN: “Voices & Shadows of the Carpathians” Postface (Part 1 of 2)

February 20th, 2015 · Books, Diaspora, Famous People, International Media, PEOPLE, quotations

Constantin ROMAN: “Voices & Shadows of the Carpathians”

Postface

“Voices & Shadows of the Carpathians”

……………………………………………………………………………………..

An Anthology of Romanian Thought –

selected and introduced by Constantin Roman

Postface: A Conspiracy of Silence

……………………………………………………………………………………..

“Now, I am a person who likes simple words. It is true, I had realised before this journey that there was much evil and injustice in the world that I had now left, but I had believed I could shake the foundations if I called things by their proper name. I knew such an enterprise meant returning to absolute naiveté. This naiveté I considered as a primal vision purified of the slag of centuries of hoary lies about the world.”

Paul Celan (1920-1970)

( “Edgard Jene and The Dream About The Dream”)

(“Collected Prose”, Carcanet, 1986)

PART 1 OF 2

One day, during a regular trip to that learned Institution off London’s King’s Road, which remains “John Sandoe’s Book shop” I was asked by one of its luminaries a simple, if justifiable question:

“Is Gregor von Rezzori Romanian?”

“He lives in Germany!?”

“No, he died in Tuscany, two years ago. His Italian widow came here to see us, recently.”

This was not a game of one-upmanship – just a friendly “away from home” rehearsal of a kind that one often heard in the ethereal but homely surroundings of this learned shop, where the owners were blessed with an abstruse yet stimulating knowledge. I was not surprised that my friend knew more than I did about the subject, but I was still taken aback – this was not a confrontation, for I was a regular of his shop and it was not the style of this charming place. I pondered for a while longer whilst trawling from the recesses of my mind for any evidence that might emerge from the “Snows of Yesteryears”, some detail that I might cling to for an answer. Then I said, perhaps a little mischievously:

“Ah, you see? He may have written in German, but he must be Romanian, as his wet nurse was a Romanian peasant.” By that I meant, inter allia, that Rezzori was nurtured, in his formative years, by the Romanian psyche, so to my mind we had a good claim to the idea of the writer’s Romanianness. Besides, such affinities were apparent from the author’s admissions in his autobiographies and novels.

It was a quiet afternoon, with one of those rare moments when there was no other client in the shop, as we were engaged in this thought-provoking repartee, so out came the next salvo:

“But, is Paul Celan Romanian?”My general attitude is never one to hide my ignorance if I were not to know the answer, perhaps because, and rather immodestly, I dare say, I am rather proud of what I do know. This is true especially on a Culture such as that of Eastern Europe, which suffered so much confusion and misunderstandings and is unjustly so sketchily known in England. But you see? This was not true in John Sandoe’s! Here the situation was different and the balance of erudition fell in their favour, in a nice way. So I said demurely:

“No, never heard of Paul Celan – who is he?”

“He is a poet and he comes from Czernowitz’ , like von Rezzori,” I was informed without a blink.

“I must read him! You see, he must be one of those exiled poets. If I had not heard of him this is because, in Romania, we were never taught at school about any of our fellow countrymen, from the Diaspora, who made their name abroad. The Communist censorship controlled all information: it always made sure that such books, written by Romanians living in the West, not only could not be found in bookshops or in the school curricula, but not even their name could be mentioned in bibliographies. It was a complete embargo of ideas. It was death by silence, it was a conspiracy of silence.”

Gradually I warmed to the subject and poured:

“This ideological censorship perpetrated by the Communists would have put to shame even the Catholic Inquisition of the Middle Ages. Names such as those of Mircea Eliade, or Emil Cioran were whispered in a hushed voice, lest one would be overheard and thrown in prison for “seditious propaganda”. Ionesco’s “Rhinoceros” was staged in Poland, but not in Romania. Even the works of those Romanian scientists who chose freedom were banned from public libraries. Literature of any kind, even scientific literature, was regarded as belonging to an “ideological domain” It remained the preserve of the Communist Party, of the one-party system, which dictated what staple diet was good for internal consumption.You see, I have been over here for many years and I still have a lot to catch up with – the “ABC” rudiments of my culture and I had not yet reached the letter “c” for Celan.”

I was neither defensive nor ashamed of myself: I was just angry at the injustice of that cultural genocide practised during forty years of Marxist régime in Romania. Curiously this practice had not completely disappeared since the so-called “Revolution”, which was the coup de palais of December 1989, which put down the tyrant and his wife!Suddenly I remembered that innocuous event, which took place in Eastbourne, several years ago, when the local branch of the “English-speaking Union” had invited the Cultural Attaché of the Romanian Embassy in London to address an audience of retired Civil servants and decent country squires. His disquisition on “Romanian Culture” was supposed to be informative. After his uninspired, uninspiring rambles, redolent of the style of the defunct Communist Party rallies, the Attaché took questions from the floor:

Caragiale, a 19th c playwright, one of the handful of pre-WWII writers approved by the Communist regime in Romania

“Well, you see? There is one,” he answered, after much thought –

“He is a 19th century playwright by the name of Ion Luca Caragiale. The

problem is that he is too subtle to do him justice in translation: he is, in

fact, untranslatable and it is a pity!”

“Quite!”

I was as startled as the rest of the audience was at this odd response. I knew of Caragiale since my school days in Bucharest, at the time of Stalin’s purges and of the national-communism of Gheorghiu-Dej. Caragiale was the darling of the régime because he lampooned the “decadence” of the Romanian upper and middle classes of modern Romania, at the end of the 19th century, when the country was a young kingdom. Caragiale was in prose for the Romanians what Gilbert and Sullivan was in rime and song for the British. He was one of the few classics of Romanian literature who could be “adopted” and “used” in his entirety by a Marxist régime, for its propaganda purposes. All other of Caragiale’s contemporaries were either conveniently forgotten, or selectively censored to be repackaged as “progressive writers”:

Great as he may have been, as a teenager, I soon got sick of this staple diet of Caragiale, marketed as the “unique genius” that Romania had ever produced! I wanted to find out more about the “other” Romanian writers like Ionesco, and Eliade who were published abroad and smuggled into the country at great risk. Now, some 30 years on, I was jerked into reality, as the name Caragiale popped up again in the words of this comrade from the Embassy. Thank God that this happened only in the back water of Eastbourne and that the audience was insignificant, otherwise the word might have spread like a foot and mouth virus to cause irreversible damage.

As it happened, it only reinforced the prejudice, albeit within a small group of English people, that Romania’s contribution, beyond Dracula and the orphanages was indeed insignificant. Witnessing this performance it was no longer surprising to come across such ill-conceived prejudices as that of Julian Barnes’s (“One of a Kind”) suggestion that all that Romania could produce was a single genius in any one field – Brancusi in Sculpture, Ionesco in Drama, Nastase in Tennis, Hadji in Football, Ceausescu in dictators… Quite a neat seditious little theory, enough to make the blood of any Romanian curdle! And yet, we Romanians we were our own worst enemies, at least if one were to judge our record by the performance of this official emissary.For me what I heard from the lips of this “nouveau communist” was untrue and outright farcical. I wanted to shout to the audience the long array of Romanian poets and novelists who lived in the West and did write in other languages or were translated in German, English, Spanish or French. There were scores of them, some being lionized in Paris, given literary accolades and much coveted Literary Prizes, others compared to the great and the good of International Pantheon of literature; “the Gorky of the Balkans” , “the best German poet since Rilke” , ” the most elegant 20th Century French writer in the tradition of Baudelaire and Valéry”…

Comments Off on Constantin ROMAN: “Voices & Shadows of the Carpathians” Postface (Part 1 of 2)Tags:"Centre for Romanian Studies - London"·"Constantin Roman"·"Voices and Shadows of the Carpathians·anthology·Brancusi·CARAGIALE·Celan·Cioran·communism·Cultural Attache·Diaspora·dictatorship·Eastbbourne·England·exile·EXILES·Geophysicist·Ionesco·London·nomenklaturist·romanian·Romanian embassy London·talk·Women's Institute

Poetry in Translation (CCCXXIV), “Păstorel” TEODOREANU (1894-1964), ROMANIA: “Sadoveanu”, in Romanian, English & French verse

February 19th, 2015 · Diaspora, Famous People, PEOPLE, Poetry, quotations, Translations

Poetry in Translation (CCCXXIV), “Păstorel” TEODOREANU (1894-1964), ROMANIA: “Sadoveanu”, in Romanian, English & French verse

Sadoveanu

“Păstorel” TEODOREANU (1894-1964)

Sadoveanu filo-Rus,

Stă cu curul spre Apus:

Ca s-arate-Apusului

Care-i fața Rusului”.

* * * * * *

Sadoveanu

“Păstorel” TEODOREANU (1894-1964)

Sadoveanu’s Russian farse,

To the West it turned its arse,

To show to the Allied Press

What’s the Russians real face.

Rendered into English by Constantin ROMAN,

© Copyright 2015, Constantin ROMAN, London

* * * * * * *

Sadoveanu

“Păstorel” TEODOREANU (1894-1964)

Sadoveanu, filo-Russe,

A devoilé son anus:

Pour montrer à l’Occident

Le visage d’un Russe brillant.

Version Française par Constantin ROMAN, Londres

© Copyright 2015, Constantin ROMAN, London

* * * * * * *

Comments Off on Poetry in Translation (CCCXXIV), “Păstorel” TEODOREANU (1894-1964), ROMANIA: “Sadoveanu”, in Romanian, English & French verseTags:Romania·Russia·sadoveanu

Poetry in Translation (CCCXXIII): Alberto BEVILACQUA (1934, Parma – 2013, Roma), EMILIA ROMAGNA / ITALY – “Anima amante”, “Suflet Îndrăgostit”, “Falling in Love”

February 17th, 2015 · Famous People, International Media, PEOPLE, Poetry, quotations, Translations

Poetry in Translation (CCCXXIII): Alberto BEVILACQUA

(1934, Parma – 2013, Roma), EMILIA ROMAGNA / ITALY – “Anima amante”, “Suflet Îndrăgostit”, “Falling in Love”

Anima amante

Alberto BEVILACQUA

(1934, Parma – 2013, Roma)

Anima amante mia per sbaglio

segnata

come una data

in un estraneo anno domini

io ti ho forse

perché ho tutto quello

che non dovrei avere per averti

mio sapore d’altrove

cerchiamo di fare in fretta

la nostra eternità

sta godendo di poche ore.

* * * * * * *

Suflet Îndrăgostit

Alberto BEVILACQUA

(1934, Parma – 2013, Roma)

Sufletul meu îndrăgostit este marcat

din greşeală

pe o filă de calendar

din ţări străine

poate îmi vei aparţine

pentrucă pot avea ori şi ce

şi nu este absolut necesar să te am pe tine

gustul meu e altundeva

încercăm să strunim

eternitatea

ca să ne bucurăm de câteva clipe.

Rendered in Romanian from the original Italian verse:

by Constantin ROMAN, London

© 2015 Copyright Constantin ROMAN, London

* * * * * * *

Falling in Love

Alberto BEVILACQUA

(1934, Parma – 2013, Rome)

My soul had fallen in love

by mistake

on a diary page

from faraway lands

maybe you will belong to me

because I could have anybody

and it’s not absolutely necessary to have you

my taste is different

we shall try to speed up Eternity

to enjoy a few moments.

Rendered in English from the original Italian verse:

by Constantin ROMAN, London

© 2015 Copyright Constantin ROMAN, London

* * * * * *

SHORT BIO: Alberto Bevilacqua Italian novelist, poet and film-maker was one of the most respected new Italian writers of the 1960s. He is best remembered for two of his novels, which he adapted and directed successfully for the screen: La Califfa (The Lady Caliph), published in 1964 and filmed in 1970, and Questa Specie d’Amore (This Kind of Love), published in 1966 and filmed in 1972.

Born in Parma, in Emilia Romagna he wrote La Polvere sull’Erba (Dust in the Grass), a book of stories about local life in Parma, which drew the attention of Leonardo Sciascia. At secondary school one of his teachers was the poet Attilio Bertolucci, father of the film-maker Bernardo. and he was encouraged to go to Rome in 1960 to find work in the Italian film industry.

Bevilacqua found jobs writing screenplays, including two for the horror director Mario Bava; one of the resulting films, I Tre Volti Della Paura (Black Sabbath, 1963), gained cult status.

La Califfa was published by the media tycoon Angelo Rizzoli and became an immediate bestseller.

The author had to wait until 1970 to find a willing producer (Mario Cecchi Gori) and star (comic actor Ugo Tognazzi, who ensured success for the film.

That success enabled Bevilacqua to direct the film of another of his novels, Questa Specie d’Amore, the story of a marriage going awry (perhaps inspired by Bevilacqua’s own). The leading role was again played by Tognazzi, with Jean Seberg as the wife. It won the David di Donatello award for best film. Bevilacqua then directed Attenti al Buffone (Watch Out for the Clown, 1975), starring the popular Italian actors Nino Manfredi and Mariangela Melato, as well as the American Eli Wallach. It was most significant for its musical score, adapted by Ennio Morricone from the works of Clément Janequin.

Alberto Bevilacqua published more than 35 books and in 1968 won Italy’s major literary award for L’Occhio del Gatto (The Cat’s Eye), another story of a failing marriage. After separating from Bucchich, he met the actor Michela Miti while making the film Gialloparma in 1999 and they began a relationship. (Abridged from the Obituary published by London’s Guardian)

Comments Off on Poetry in Translation (CCCXXIII): Alberto BEVILACQUA (1934, Parma – 2013, Roma), EMILIA ROMAGNA / ITALY – “Anima amante”, “Suflet Îndrăgostit”, “Falling in Love”Tags:"Centre for Romanian Studies - London"·"Constantin Roman"·"Poetry in Translation"·Alberto BEVILACQUA·editor·EMILIA ROMAGNA·English·Italian·Italy·London·Parma·Roma·romanian·traducere·translation·“Anima amante”·“Falling in Love”·“Suflet Îndrăgostit”

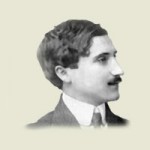

Poetry in translation (CCCXXII): Ion MINULESCU (1881– 1944), (ROMANIA) – “Rugă pentru Duminica Floriilor”, “Palm Sunday Prayer”

February 14th, 2015 · Books, Famous People, PEOPLE, Poetry, quotations, Translations

Poetry in translation (CCCXXII): Ion MINULESCU (1881– 1944), (ROMANIA) – “Rugă pentru Duminica Floriilor”, “Palm Sunday Prayer”

Ion MINULESCU

(1881– 1944)

Palm Sunday Prayer

Release me, oh, good Father, of what I swore to be…

Forgive my errant pathways: accept them as they are:

A hymn of early prayers, before Thy Holy See,

To add a limpid raindrop

On Thy eternal breeze…

Release me, oh, good Father, of trying to endure

The granite cut with ease,

The bronze made of manure…

A glittering pearl necklace, made of sunflower seeds,

A double-winged Pegasus out of a humble bee …

Forgive me, though, dear Father, of this – mine foolish jest,

To have imagined Thee –

As I thought might be best…

But the World was too pallid, than I thought it might be.

My Lord, sprinkle my eyebrows, with drops of holly sea.

Chastise my sinful body,

Behold my tongue of python,

Remove the foolish demon, that pronounced the unheard.

Do give zest to my body, depicted in Your icon…

To forget I was ever beholden by Thy word!

Rendered in English from the original Romanian verse: by Constantin ROMAN, London

© 2015 Copyright Constantin ROMAN, London

* * * * * * *

Ion MINULESCU (1881– 1944)

Rugă pentru Duminica Floriilor

Dezleagă-mă, Părinte, de ce-am jurat să fiu

Şi iartă-mă că-n viaţă n-am fost decât ce sunt –

Un cântec prea devreme, sau poate prea târziu,

Un ropot scurt de ploaie

Şi-un mic vârtej de vânt…

Dezleagă-mă de vină de-a fi-ncercat să fac

Granit din caramidă

Şi bronz din băligar,

Colan de pietre scumpe din sâmburi de dovleac

Şi-un Pegas cu-aripi duble din clasicul măgar…

Şi iartă-ma că-n viaţă n-am fost decât aşa

Cum te-am văzut pe tine –

C-aşa credeam că-i bine!…

Dar azi, când văd ca-i altfel de cum am vrut să fie,

Stropeşte-mi ochii, Doamne, cu stropi de apă vie,

Retează-mi mâna dreaptă

Şi pune-mi strajă gurii,

Alungă-mi nebunia din scoarţele Scripturii

Şi-apoi desprinde-mi chipul de pe icoana Ta

Şi fă să uit c-odată am fost şi eu ca Tine!…

* * * * * * *

SHORT BIO:Ion Minulescu (6 January 1881 – 11 April 1944) was an avant-garde poet, novelist, short story writer, journalist, literary critic, and playwright. Often publishing his works under pseudonyms, he journeyed to Paris, where he was influenced by the growing Symbolist movement and Parisian Bohemian life. A herald of Romania’s own Symbolist movement, he had a major influence on local modernist literature, and was among the first local poets to use free verse.Between 1900 and 1904, Minulescu studied Law at the University of Paris, during which period he was an avid reader of Romantic and Symbolist literature of Gérard de Nerval, Arthur Rimbaud, Charles Baudelaire, Aloysius Bertrand, Jehan Rictus, Emil Verhaeren, Tristan Corbière, Jules Laforgue, Maurice Maeterlinck, and the Comte de Lautréamont. He also became close to Romanian artists present in Paris — Gheorghe Petraşcu, Jean Alexandru Steriadi, Cecilia Cuţescu-Storck, and Camil Ressu, as well as to the actors Maria Ventura and Tony Bulandra. Among the defining moments of his life in Paris was his meeting to the poet Jean Moréas, who apparently urged him to write his poetry in French. On his return to Romania he began cultivating relations with the local art dealer Krikor Zambaccian and the painter Nicolae Dărăscu. Minulescu and Anghel became close friends, and together translated pieces by various French Symbolists such as Albert Samain, Charles Guérin, and Henri de Régnier: these were later compiled in a single volume, in 1935. Earlier on, in 1928, Ion Minulescu was awarded the National Poetry Prize. He died from a heart attack during World War II, as Bucharest was the object of a large-scale Allied bombing. He was buried at the Bellu cemetery.

Comments Off on Poetry in translation (CCCXXII): Ion MINULESCU (1881– 1944), (ROMANIA) – “Rugă pentru Duminica Floriilor”, “Palm Sunday Prayer”Tags:"Constantin Roman"·"Romanian into English"·Center for Romanian Studies - London·Dumnezeu·editor·God·Ion Minulescu·lawyer·Literature·Paris·poet·poezie·Romania·Symbolist·traducere·translation·translator·verse·“Palm Sunday Prayer”·“Prayer”·“Rugă pentru Duminica Floriilor”

Poetry in translation (CCCXXI): Constantin ROMAN (ENGLAND) – “In Memoriam”

February 13th, 2015 · Diaspora, International Media, PEOPLE, Poetry, Translations

Poetry in translation (CCCXXI): Constantin ROMAN (ENGLAND) – “In Memoriam”

IN MEMORIAM

Constantin ROMAN

England

We shall remain prostrate by Gravity

And our latent self-esteem,

As we will lose all our levity

And the professional pipe dream…

Don’t cry, you, milligal and lonely oersted,

As the old man died, with alacrity.

Therefore, we shall stampede, in earnest,

To grab his seat, at the Academy.

But, mindful of the world’s Ecology,

We’ll mummify his body for the Nations,

To be preserved for future generations

And be admired by Humanity.

And as we’ll find him pickled, in preserves,

Displayed amongst the vile orangutans,

We shall forgive him his shenanigans,

To grant him the respect that he deserves.

Rendered in English from the original Romanian verse: by Constantin ROMAN, London

© 2015 Copyright Constantin ROMAN, London

* * * * * * *

ROMAN is a Professor Honoris Causa and a Commander of the Order of Merit. He lives in London, where he is a Member of the Society of Authors, an independent consultant and a contributor to British media.

ORDER/Cumpara:

http://www.blouseroumaine.com/buy-the-book/index.html

– See more at: http://www.romanianstudies.org/content/2009/04/an-alternative-anthology-of-romanian-women/#sthash.f5NRx2GJ.dpuf

Comments Off on Poetry in translation (CCCXXI): Constantin ROMAN (ENGLAND) – “In Memoriam”Tags:"Centre for Romanian Studies - London"·"Constantin Roman"·"In Memoriam"·ecology·editor·English·literary England·Literary Romania·London·orangutan·pipe dream·poet·poetry·romanian·self-esteem·shananigans·translator

Poetry in Translation (CCCXX): George TOPÂRCEANU (1886-1937), ROMANIA – “L’âne philosophe”, “Măgarul filosof”, “The Philosopher Ass”

February 8th, 2015 · Diaspora, Famous People, PEOPLE, Poetry, quotations, Translations

Poetry in Translation (CCCXX): George TOPÂRCEANU (1886-1937), ROMANIA – “L’âne philosophe”, “Măgarul filosof”, “The Philosopher Ass”

L’âne philosophe

George TOPÂRCEANU (1886-1937)

Un jeune âne amoureux d’une noble cavale,

Lui demanda la main (le sabot de devant).

— Mais… vous êtes du peuple, et moi — je suis pur sang,

Je vous ferai cocu! lui promit-elle.

— J’avale

Tout ce que vous voudrez! dit l’âne sans émoi,

Car…

Moralité:

Promettre c’est noble, tenir serait bourgeois…

* * * * * *

Măgarul filosof

George TOPÂRCEANU (1886-1937)

Îndrăgostit lulea de o iapă de rasă,

Măgarul i-a propus, s-o ia la el acasă.

– Dar nu se poate, dragă,- eşti un nenorocit…

Iar eu fiind de pur-sânge, o să te-nşel cumplit!

– Vei fi a mea prinţesă de măgar amorez…

Şi-n sine s-a gândit:

S-o promiţi este nobil, dar s-o ţii e burghez…

Rendered in Romanian from the original French verse: by Constantin ROMAN, London

© 2015 Copyright Constantin ROMAN, London

* * * * * * *

The Philosopher Ass

George TOPÂRCEANU (1886-1937)

A young ass fell in love with a pedigree mare

And asked for her hand (her shoe as a token)

– But you are of low breed and not even broken…

I will make you a cuckold! she said. – I don’t care

– I’ll give all you dream of! said the ass without quivers,

Because …

As the old saying goes:

The Noble may well promise, but the Bourgeois delivers.

Rendered in English from the original French verse: by Constantin ROMAN, London

© 2015 Copyright Constantin ROMAN, London

* * * * * * *

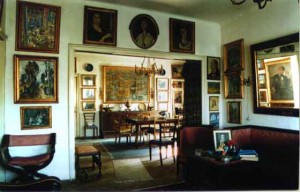

SHORT NOTE: The Memorial house George TOPÂRCEANU has been gifted, in 1966, by the poet’s late wife. This had since been declared a historic monument. Here the great national poet had lived for eight years, before WWII and apart from personal archives, it contains the poet’s library. Although the poet was born in Bucharest and died at Iasi, in Moldavia, where he was invited to be an editor, his own mother lived in this same village of Nămăești, where she founded an atelier creating traditional rugs. The poet’s spouse and son lived in the current house, before it became a museum.

SHORT NOTE: The Memorial house George TOPÂRCEANU has been gifted, in 1966, by the poet’s late wife. This had since been declared a historic monument. Here the great national poet had lived for eight years, before WWII and apart from personal archives, it contains the poet’s library. Although the poet was born in Bucharest and died at Iasi, in Moldavia, where he was invited to be an editor, his own mother lived in this same village of Nămăești, where she founded an atelier creating traditional rugs. The poet’s spouse and son lived in the current house, before it became a museum.

The 19th c. Memorial house is built in the typical style of the Carpathian foothills and is situated in the village of Nămăești, Valea Mare-Pravăț, county Argeș, some 115 Km NW of Bucharest.

Comments Off on Poetry in Translation (CCCXX): George TOPÂRCEANU (1886-1937), ROMANIA – “L’âne philosophe”, “Măgarul filosof”, “The Philosopher Ass”Tags:"Centre for Romanian Studies - London"·"Constantin ROMAN" London·"County Argeș"·"George TOPÂRCEANU"·"Memorial House"·"Poetry in Translation"·ass·Bourgeois·cuckold·editor·French into English·French into Romanian·low breed·mare·Nămăești·noble·pedigree·poet·promise·Romania·TOPÂRCEANU·traducteur·traduction·translation·translator·writer·“L’âne philosophe”·“Măgarul filosof”

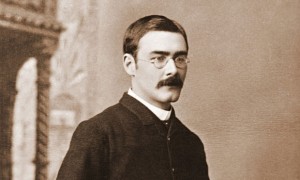

Poetry in Translation (CCCXIX): Rudyard KIPLING (1865-1936), ENGLAND – “Mother o’ Mine”, “O, mamă, dulce mamă!”

February 5th, 2015 · Famous People, Poetry, quotations, Translations

Poetry in Translation (CCCXIX): Rudyard KIPLING

(1865-1936), ENGLAND – “Mother o’ Mine”, “O, mamă, dulce mamă!”

Mother o’ Mine

Rudyard KIPLING (1865-1936)

If I were hanged on the highest hill,

Mother o’ mine, O mother o’ mine!

I know whose love would follow me still,

Mother o’ mine, O mother o’ mine!

If I were drowned in the deepest sea,

Mother o’ mine, O mother o’ mine!

I know whose tears would come down to me,

Mother o’ mine, O mother o’ mine!

If I were damned of body and soul,

I know whose prayers would make me whole,

Mother o’ mine, O mother o’ mine!

* * * * *

O, mamă, dulce mamă!

Rudyard KIPLING (1865-1936)

De aş fi spânzurat la răscruce de drum,

O, mamă, dulce mamă!

Eu ştiu c-al tău dor, m-ar urma ori şi cum,

O, mamă, dulce mamă!

De aş fi înecat, în adanc de ocean,

O, mamă, dulce mamă!

Ştiu că lacrima ta nu ar curge în van,

O, mamă, dulce mamă!

Dac-al meu trup şi suflet în gheenă ar fi,

Numai ruga ta, mamă, m-ar putea mântui.

O, mamă, dulce mamă!

Rendered in Romanian by Constantin ROMAN, London

© 2015 Copyright Constantin ROMAN, London

* * * * * * *

SHORT NOTE: The mother-son relationship, the most prevalent in Kipling’s fictions is best reflected his poem “Mother o’mine”. The repetition of o’ in the refrain visually shows the wholeness of the maternal love and that of the mother-son union, as well as the opening of a gap, or a lack, in himself, which the male child calls upon his mother to fill in.(‘The Cambridge Companion to Rudyard Kipling’, ed. Howard J. Booth, chapter ‘Kipling and gender’, op. cit. pp. 69)

Comments Off on Poetry in Translation (CCCXIX): Rudyard KIPLING (1865-1936), ENGLAND – “Mother o’ Mine”, “O, mamă, dulce mamă!”Tags:"Centre for Romanian Stdudies - London"·"Constantin ROMAN" translator·"Poetry in Translation"·dulce mamă!”·editor·England·english - Romanian translation·love·mamă·Rudiard Kipling·sole·“Mother o’ Mine”·“O·“Prayer”

Poetry in Translation (CCCXVIII): Marjorie Lowry Christie PICKTHALL (1883-1922), ENGLAND/CANADA – “Marching Men”, “Soldaţi”

February 3rd, 2015 · Books, Famous People, International Media, OPINION, PEOPLE, Poetry, quotations, Translations

Poetry in Translation (CCCXVIII): Marjorie Lowry Christie PICKTHALL

(1883-1922), ENGLAND/CANADA – “Marching Men”, “Soldaţi”

MARCHING MEN

Marjorie Lowry Christie Pickthall

(1883, England – 1922, Canada)

Under the level winter sky

I saw a thousand Christs go by.

They sang an idle song and free

As they went up to calvary.

Careless of eye and coarse of lip,

They marched in holiest fellowship.

That heaven might heal the world, they gave

Their earth-born dreams to deck the grave.

With souls unpurged and steadfast breath

They supped the sacrament of death.

And for each one, far off, apart,

Seven swords have rent a woman’s heart.

* * * * * * *

SOLDAŢI

Marjorie Lowry Christie Pickthall

(1883, Londra, Anglia – 1922, Canada)

În iarna cerului de plumb,

Văzut-am mii de sfinţi trecând.

Cântau un imn să uite-amarul,

Purtând, cu fruntea sus, calvarul.

Nepăsători si surâzând,

Mergeau la pas, rând după rând.

Tu, dă-le pace, Doamne Sfinte,

Cu flori s-acopere morminte!

Cu fruntea sus, în faţa morţii,

Au luat un sacrament, cu toţii,

Ştiind că au lăsat la vatră

O fiinţă ce le-a plâns de soartă.

Rendered in Romanian by Constantin ROMAN, London

© 2015 Copyright Constantin ROMAN, London

* * * * * * *

After receiving her education at Bishop Strachan School for Girls, she worked in the library of Victoria College University of Toronto, where she helped compile a bibliography of Canadian poetry. Pickthall first published stories and poems in 1898 in the Toronto Globe. Her literary output, which includes several hundred short stories and five novels, nearly halted at her mother’s death in 1910, but Pickthall returned to England from 1912 to 1920 and recovered her will to write. She lived both at a cottage at Bowerchalke, near Salisbury, and in London. During this period she published two volumes of poetry: The Drift of Pinions (1913) and The Map of Poor Souls (1916). Her war-time work overseas included farming, training as an ambulance driver, and working in the South Kensington Meteorological Office library. Late in this period she wrote in a letter dated December 27:

“To me the trying part is being a woman at all. I’ve come to the ultimate conclusion that I’m a misfit of the worst kind, in spite of a superficial femininity — emotion with a foreknowledge of impermanence, a daring mind with only the tongue as an outlet, a greed for experience plus a slavery to convention — what the deuce are you to make of that? — as a woman? As a man, you could go ahead and stir things up fine”.

Homesick, she sailed back to Canada in 1920 and, after a brief time with her father in Toronto, settled in a cottage on Vancouver Island. She died unexpectedly from an embolus in the spring of 1922 and was interred in St. James’ Cemetery in Toronto.

After her death, three volumes of her poetry came out: “The Woodcarver’s Wife and Other Poems” (1922), “Little Songs” (1925), and “The Naiad and Five Other Poems” (1931). Her father compiled and published her “Collected Poems” in 1925 and again, definitively, in 1936.

Victoria College holds a major collection of her manuscripts.

(Modified from: http://rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poets/pickthall-marjorie)

Comments Off on Poetry in Translation (CCCXVIII): Marjorie Lowry Christie PICKTHALL (1883-1922), ENGLAND/CANADA – “Marching Men”, “Soldaţi”Tags:"Constantin ROMAN" translator·"Marjorie Lowry Christie PICKTHALL"·"Poetry in Translation"·calvary·Canada·Canadian poetry·death·editor·England·grave·heaven·Literature·SOLDAŢI·translation·War·WWI·“Marching Men”