ETERNAL REST IN BUCHAREST (PART 1 OF 6)

“En Roumanie tout est possible et rien

ne m’étonne plus!” (Emil Cioran)

1. There was a strange mixture of the macabre and the comic in the funeral proceedings which were unfolding in front of my eyes in the Chapel of Rest of the Romanian Orthodox cemetery in Bucharest, like a surreal play of the Theatre of the Absurd by Eugene Ioneco. The family burial plot was in one of the grandest and most elegant cemeteries in the country, recently declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site because of its grandiose mausoleums, decorated with bronze sculptures and statues carved in Carrara marble. These were all witness to a faded historical past. Now all these glories were almost all forgotten. This was the world of pre-War Romania during which aunt Angelica spent half of her life, the second half she lived under the communist dictatorship and this we were going to bury today. Following several generations of forebears who went to their Maker, with Angela’s demise the last vacant crypt in the family vault was going to be filled. What it meant to me, was that the vault became rather crowded and that I no longer stood a chance of joining my parents, grandparents and great grandparents: that made sense as I now belonged to another country and this was my last link which I was about to bury six feet under the ground.

My short visit as the last member of Angela’s close family, now living in the West, was prompted by a short telegram from a distant cousin in Bucharest:

“A murit Tanti Angelica. Vino acasa sa aranjezi funeraliile”

(Aunt Angela has passed away.. Come home to organise funeral)

– meaning, really, to officiate the role of “Maître de cérémonie”, well, a kind of majordomo, like in the gentlemen’s clubs of London…

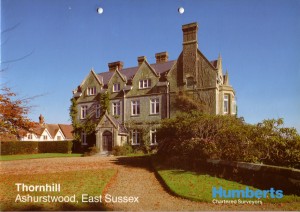

What seemed strange in this odd message, which arrived out of the blue, in my London home was that I was asked to return home whilst, by that time, I lived far longer abroad than I ever lived in Romania, nearly twice longer, I should say, and far longer than I cared to keep a record of. By then my life was filled with momentous events, which charted a road of no return to Ceausescu’s dictatorship: I had a Cambridge degree, I was gainfully employed by an American Oil Company in London, I was the owner of a nice house with a manicured croquet lawn (my interpretation of being mistaken for an English gent, which I was not). I owned an estate with centuries-old trees, including a majestic sequoya, a cedar of Lebanon and a lake stocked with carp… More to the point I was married into an English family, where high breeding, an Army background and low-brow intelligence, counted for more than a University degree, be it even from Oxbridge.

In fact I never had either patience or inclination to contemplate all these distinctions, as I considered myself very much of ‘middle brow’ stock. The in-laws, or shall I call them the ‘outlaws’, were middle class too, or, at best, upper middle class, because of their associations with the British Army upper echelons and with the landed gentry.

It amused me no end to hear them complaining about a prospective daughter-in-law being the offspring of a “mere army major!”

– ‘But excuse me, this is exactly what your own father is’, I reminded my better half, to which she corrected me:

– ‘Ah you see, the difference being, had Father not resigned his commission, as a young Major, to take up farming, he will have become, by now, a General like grandfather, great grandfather and many generations before him all the way to East India Company! Besides, father belongs to a much better regiment, ‘The King’s Own’, whilst Sue’s father comes from an obscure army regiment, whatever that may be… Not to mention the late uncle Bob who was a Colonel-in-Chief of the Cavalry regiment” and a benefactor of the Army Museum and of the Scottish Church in London’.

‘It makes sense, doesn’t it? I could not agree more! What a missed opportunity! What a field day to have had a Field Marshall as a father-in-law!’ At this sombre thought my protestations froze in my gullet.

Wife completely missed the jibe, as she pronounced the indictment of her future sister-in-law:

‘She was after the honey pot, this is what Mother said.’

‘But your Mother was bound to say that, you admitted it yourself, about all her children’s prospective matches, suspected of ‘being after their money!’

It ached me no end about my Mother-in-law trumpeting loudly to all who cared to hear it and especially to those who did not want to, that the only attraction her children ever possessed was their inheritance and nothing else! How beastly of her! But how was I to know all these subtleties, because by the time I woke up to this reality check I already had three wonderful children. They did not speak Romanian, because their mother did not and anyway I was most of the time absent from home, during the week and they were asleep as I returned home from work, in the evening. By the time they grew up enough to sense the difference, children knew precious little about Romania, in a patchy manner, from anecdotes and hearsay. Aunt Angelica was part of this rich folklore, a last link with the past and now this link was broken, with the last close member of the family gone.

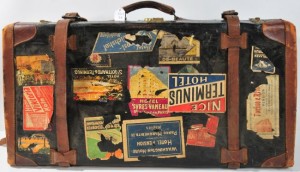

Compared to the airport I knew when I last flew out of the country, during the “Golden Era” (Epoca de Aur, no less!) of blissful communism, Bucharest International Airport was buzzing with a new life of free enterprise, which was reminiscent of provincial country funfairs. While waiting for the arrival of my suitcase where I threw in a hurry a few personal belongings, before I left London and a second larger suitcase with a lot of presents for long-lost relations, I noticed this character who got hold of my bags ready to bundle them in an unmarked taxi – I pounced on him but would not retrieve my belongings before I paid a tip to transfer the luggage into the cousin’s old car, which was waiting for me. I recognised her instantly because of her haircut reminiscent of Ana Pauker, a kind of boyish lesbian hair cut, too short for a woman, almost masculine. But above all, it was her unmistakeable “strungareata” – the distinctive gap between her front teeth, which decorated the smile of her full-Moon face, I found her always unattractive, in a manner which betrayed her unmistakable extraneous origins, from a mining community in the Carpathian mountains of Transylvania.

She got out of the car with some difficulty, because of her outsize girth and effected an embrace: we hardly knew each other in Romania, because I was too young at the time and the age difference did count, especially that she was really only a cousin-in-law and the widow of my late father’s first cousin. We only met at family funerals, before I left Romania in a hurry, never to return. We both feigned an unbound elation on embracing each other after three long decades:

– ‘Te-ai ingrasat, arati bine!’ (You put on weight, you look good!).

Oh, here we are, the famous Romanian adage, whereby telling somebody that he put on weight was a compliment, inferring a life of plenty and of professional achievement: ‘esti gras si bine’ literally meaning ‘you are fat and well’, always said in envy, as a hang over from the atavistic memory of centuries-old famine, when only fat people survived. What was absolutely sure, even for Romanian women, was that ‘plump’ was better than spindly and if you had the girth, the size of an inflatable mattress, you stood a better chance of getting married, then say if you were a lanky beauty, fit only for the cat walk. Even the popular ditties reflected this philosophy:

Sărut mâna pentru masă

C-a fost bună şi gustoasă

Şi bucătăreasa grasă.

Which, in the English vernacular translation, would more or less sound like:

Kiss your hand, Ma’am, for the pastry,

And the meal, which was so tasty,

For the coffee and all that,

As the cook was nice and fat’.

Not a good start, the story of the suitcase, followed by the reminder that I was overweight. With adrenaline still pumping, after this inauspicious preamble, I woke up to this reality check: I really felt that I was out of touch with Romania and my self-defense short of appropriate interjections. This was the country, which was hoping to become some day a member of the EU… Did not Tony Blair referred to it as being “on the threshold of Europe”?… Of course, when the Romanians heard all this, thinking of themselves as Europeans of the best type, they got in a funk: how wrong Blair could have been! To me, after three decades of absence this country looked more like the worst corner of the Middle East!

Before I could erase from my mind this first impression it only got reinforced by the dilapidated state of my cousin’s car, a twenty-year old vintage “Dacia” (a kind of Communist “Trabant”, Romanian-style) rattling in an alarming manner, as if it was going to fall to pieces, when negotiating the potholes on the road. Of course, the oncoming traffic trying to avoid exactly the same potholes would often bring us to near-collision course. The ensuing exchanges of the most colourful, if imaginative, vernacular were typical of Bucharest and raised the winter temperature by several degrees. I tried to reduce the tension by bringing some good cheer for the driver, when I ventured tentatively the news:

– I brought you a few presents from London, for all your trouble!

She looked at me in disbelief because she had bigger and better ideas of her own, as I was going to find out instantly:

– As you see, what I really need is a new car!

– I can see that, I added, not knowing what to make of this

– Well, why don’t you send me one from England?

– Why should I? I answered, as such direct, no-frills question deserved a fittingly blunt retort.

– Because till the end of the year we do not pay VAT on imported second-hand cars

– Aha, how very interesting, but what will you be doing with an English car which has the stirring wheel on the right: in England we drive on the left side of the road – you know?

She did not think of this unexpected inconvenience and fearing that she might ask me to send her a car from France, or Germany, indeed from anywhere, I added cautiously;

– Besides you will have problems with spare parts and these are expensive, you know? Not to mention the service!

– Besides you will have problems with spare parts and these are expensive, you know? Not to mention the service!

– In England you have to do things differently from everybody else, she retorted, merely to counteract the unexpected show-down

– Yes we do and I thank God for it – for starters we do not have potholes on the roads!

As I barely finished my sentence a new near-collision brought mercifully this awkward conversation to a halt and before long we arrived “home”….

Well, in fact I no longer had a “home” by that time because my parents died only months before Ceausescu’s overthrow. This prompted some dutiful cousins to make sure that parents’ flat was sold and all chattels with it so that they could buy themselves a more spacious apartment. For them I was conveniently out of the way, I simply did not exist, as I lived on the other side of the barbed wire of Romania’s prison-state, beyond the Iron Curtain. They knew that they could act as they pleased, with impunity: they gave evidence that parents had ‘no surviving children’ and so they declared themselves ‘sole heirs’, oh, yes!! Now in the town of my childhood I had no longer an anchor other than the family graves and I felt rudderless. All my personal memories were carefully erased, if not by Ceausescu’s bulldozers and expropriations, then by the rapacity and opportunism of surviving relations, whose life exertions under Communism taught them the harsh reality of survival of the fittest: in such environment all compromises and all blows below the belt were permitted, provided that it secured a minimum of advantage. Why should I blame them? I certainly had no right to! I was lucky to be out of this game.

– Where is Angela, I asked tentatively, trying to show some decorum for the event for which I was summoned to perform the offices of ‘High Priest’, as the closest and eldest relation of the deceased.

– She is in the ‘Chapel of Rest’: you can bring her some flowers tomorrow and we shall have to pay for the wreath and bring it with us at the same time.

– Isn’t it a little too early before the funeral to put her in this Chapel, on everybody’s view, instead of keeping her refrigerated in the municipal Central Mortuary? What if she started to smell?

– Don’t you worry, this is the custom. We did it all according to custom, as you were not here. She was gutted out and was filled with formaldehyde.

– What do you mean ‘she was gutted’? It sounds like a salmon at a fishmonger’s. Was she filleted as well? I AM gutted to hear all these details!

– Are you squeamish? This is the Law of the Land and we have to bury the dead within three days. Besides, the Chapel is not heated.

Oh yes, I did indeed remember the glacial Chapel during the harsh winter of Bucharest when attending Grandfather’s funeral service, which lasted shy of two hours. The mourners nearly all froze, standing around the open coffin, with the two Orthodox priests in richly embroidered vestments, wafting clouds of incense from their silver incense burners, during unending Byzantine chants and prayers for the absolution of the sins of the dearly departed and closing the performance with the ‘Vesnica Pomenire’ (Eternal Remembrance)

– Would grandfather have committed so many earthly sins as to require such an extended service? I asked Father

– Don’t you mind all this and be quiet, my son: this is the custom. Grandfather being issued from a long lineage of clerics he deserved a fully-fledged service.

My thoughts quickly brought me back to Aunt Angela’s funeral:

– Well, I said, if such is the case I better make my way to the hotel, as I had a long journey starting in the middle of the English countryside, before I went to Heathrow and finally made it to Bucharest.

– You mean to say you booked a room at the hotel, rather than stay with us? But this is madness – it will cost you a lot of money. I prepared a bed for you here.

– I know, thank you, my dear, you are very kind as usual. I reflected for a minute thinking of the nightmare of living with my cousin at such close quarters: she would have finished me off – the sodding, unhappy bastard! I felt as if I had to buttress my refusal with a new line:

– It is no good, dear. I am a very bad guest; I snore and fart in my sleep and I wake up at least twice, if not three times in the middle of the night to have a pee… you know? old men’s bladders do not function properly anymore. I will be a nuisance and in the dark I am likely to stumble over your cat!

– But we are used to all this: we fart too, you know? What is different in all that? You mean to imply that your English farts smell differently?

– Most certainly, my dear: they are stinking bombs, truly lethal!

– But think that your hotel is extortionately expensive, it must be: I bet you booked at the Hilton, knowing you! we could have done with this money ourselves, we have so many needs!

– No, as a matter of fact I booked at the Continental. I will call you in the morning.

What was nice about this direct language to which I was no longer used and nearly forgotten was the sheer unadulterated verb: why beat about the bush when you can go straight to the point? Quite! Memories came flooding back, again and again, in droves and far from being shocked, or ruffled, I found it endearing and mildly amusing in a detached sort of way: it was a manner of insulating oneself from such verbal aggression, short of putting on an armoured protective outfit and pretend that I was both aloof and insensitive to my relations’ plea.

For a split second, seeing her crumpled face dissolve in utter distress, I felt a pang of remorse, so I added

– I know dear, don’t you worry, I thought of all that. Look this other suitcase is full of presents, most of them for you and only a few trinkets for the other cousins. You will get all the expenses refunded and a lot more for all your trouble to have looked after Angela through her difficult times. Now I must go as I am truly exhausted.

– But I arranged dinner for us and a few relations.

– Not to worry dear, you will explain all that, and tell that we shall have a good wake together after the funeral, when we can keep each other’s company and say all we want to reminisce about. Besides, I believe that you and I will see more of each other to sort out Angela’s studio. It must be full of old furniture, papers and stuff and it will all have to be sorted out before I go.

– We already started to sift through, you know? we could not wait till you came in the last minute. She never threw out a hairpin, you know? junk which survived the war and the earthquakes, some of it going back to 1900.

– Very well, so I see: Angela’s dining room and paintings are already here in your flat, I can see that! They belonged to grandfather, you know? I remember them vividly since I was a child… And those paintings were painted by grandmother at the Fine Arts school in Paris, at the ‘Academie Julliard’and later on with Sava Hentia in Bucharest.

– Angela gave all these to me before she died.

– I should think so, dear: you were very good to her, I know. I will make an offer which you cannot refuse, for these paintings, so that you will not feel hard done, I assure you. The furniture you can keep. Oh look, how nice, these were my mother’s porcelain flowers: my children gave these to her when she visited us in England before she died.

– Oh your mother gave me these ages ago, do you mind?

– Look, I am no good at commercial transactions after a long haul: I shall see you tomorrow. When should we meet?

– Early morning we shall have still formalities to sort out at the cemetery and then the lawyers.

– Well couldn’t they wait until after the funeral?

– The cemetery can’t: we need a signature from you before she could be buried

– Ok, not to worry. My driver is here, dear.

– You mean you have a driver?

– A colleague at the Geological Institute lent me their driver, so that we do not use your time and petrol. Let me take my luggage downstairs.

– You can leave the suitcase with presents here so that you don’t carry it all the way and back again…

– That’s right: I have not thought that far, I shall. We’ll speak on the phone tomorrow.

No Comments so far ↓

Like gas stations in rural Texas after 10 pm, comments are closed.