Hungarian ‘savoir-faire’ and Romanian navel-gazing:

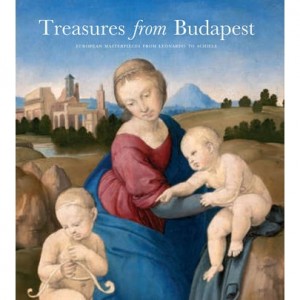

Footnote to the Hungarian Exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, Piccadilly on: “Treasures from Budapest – European Masterpieces from Leonardo to Schiele”

LOCATION: For those readers who would not know, the Royal Academy of Arts is situated in Burlington House, in London’s West End avenue of Piccadilly: this is a prestigious location for several reasons, first of all because the hosting Institution is a venerable British household name of an artistic tradition going back to the 18th century. The RA, for short, organizes regular exhibitions of greatest prestige, on par with those of the greatest London Museums and commands an extensive following. The venue is Burlington House, one of the few aristocratic houses built in the 17th century to be located near to the Court of St James’s, which at that time was the main residence of the English Monarchs. Even today the foreign diplomats coming to London are “accredited to the Court of St James’s” although in fact they are received by HM the Queen at Buckingham Palace. This makes the RA and Burlington House being situated near all the historic, political and cultural focal points in Central London such as the Royal Society, Clarence House, all the Gentlemen’s Clubs, Christies Auctioneers, all the important Art galleries of St James’s and Bond Street, Apsley House at Hyde Park Corner and all the best shops in Piccadilly and Regents Street and Bond Street, not to mention the tourists attractions of Piccadilly Circus, the Trafalgar Square with the National Gallery and National Portrait Gallery and Soho, the Theatres and the Government buildings in Whitehall.

Given the above pointers it is clear that the Hungarian exhibition “Treasures from Budapest” of October 2010 could not have chosen a better location: it is central, it is prestigious, it is in an elegant building with excellent tradition and exhibiting space and a huge pull to the general and specialist public from England and abroad.

The Hungarian PR coup is that much more remarkable as the RA plans events five to seven years in advance before a particular proposal could find a slot and eventually could materialize: some efforts such as the proposed exhibition of art treasures from the private Collection of the Princes of Liechtenstein stumbled on administrative difficulties which caused it to be abandoned recently: the Hungarians were lucky because their exhibition was brought forward; we understand from the British curators that their Hungarian counterparts in Budapest were co-operative, accommodating and extremely helpful: all to a good end! This venture will not have been made possible without the financial support of the OTB Bank: these days it is a sine-qua-non condition to have wealthy and willing sponsors and our Hungarian friends understood this simple truism.

THE EXHIBITION:

This exhibition showcases the breadth and wealth of one of the finest collections in Central Europe. It comprises works from the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, with additional key loans from the Hungarian National Gallery. Most of the works come from the early collection of the Princes Esterhazy, great patrons of the arts: indeed the name is immediately connected with the baroque period when Haydn was a court Kapellmeister but also the princes were spending lavishly on commissioning and collecting paintings; the Raphael which is chosen for the poster is indeed a masterpiece of World art and is known as “The Esterhazy Madonna” (1508).

Other signal canvasses which this event celebrates is Leonardo (Study of soldiers head) at one end of the spectrum and at the other to Egon Schiele a main representative of early 20th century Austria Hungary and a protégé of Gustav Klimt. The Northern European schools are represented by Lucas Cranach, Rubens and Rembrandt, and the French by Poussin, Claude and Laurent de la Hyre. Highlights from the museum’s superb collection of works on paper include two studies by Leonardo for his mural of the Battle of Anghiari, fine drawings by Dürer and Altdorfer, and figure studies by Tiepolo and Watteau.

Works by Royal Academicians Sir Joshua Reynolds, John Constable and Angelica Kauffman. Amongst other works once owned by the British is for example a Cornelis van Poelenburgh’s portrait of the children of the Elector Palatine Frederick V – known as the “winter king” – was owned by Charles I and has his crowned monogram on the reverse of the panel.

Also, the small 1814 oil sketch by John Constable of East Bergholt, which not only depicts a huge gold standard at the heart of a massive peace celebration in the village but also an effigy of a beaten Bonaparte in his tricorn, hanging from a gibbet.

It is understandable that the central European artists, in particular German and Austrians would have a greater weight in the Hungarian art collections and more recently these made the object of press headlines as legal disputes arose over the original ownership and restitution of art treasures plundered by occupying armies from East and West: if the Western museum were good at returning their disputed oil paintings, the Russians had no such scruples – but the organizers of the RA could not be too careful as they covered all eventuality in a disclaimer under the banner:

The Esterhazys were astute and discerning Collectors hence the importance and the variety of the 200 exhibits of this London venue: drawings and sculpture from the early Renaissance to the twentieth century. Selected works by artists apart from Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael but also El Greco, Rubens, and Goya, a collection completed after 1871 the year where the Hungarian state acquired the Esterhazy collection with more recent artists such as Manet, Monet, Gauguin, Schiele and Picasso.

WHY talk about a Hungarian exhibition on a Romanian Cultural Studies site?

WHY indeed! At a first glance it may appear fortuitous to do just that and yet there may be many reasons to have done it and one can think of a few, at random:

* One could immediately think of the common historical space of Central-Eastern Europe at the archaeological treasure troves found in Transylvania before WWI and now belonging to Museums of Hungary.

* One could equally think of the Bibliotheca Corviniana, of that Hungarian Renaissance king of Romanian stock – Matthias Corvinus, born in Cluj/Koloszvar and his stupendous collection of illuminated manuscripts, mostly dispersed but some returned to Budapest, during the 19th century, by the Sultan.

* One could further connect with the Transylvanian origins of the Esterhazys before they were ennobled by the Habsburgs or about the collections of other Hungarian aristocrats some of whom were magyarized Romanians such as the Banffy or the Szeczeny.

* Last but not least the post-Impressionist artist School of Baia Mare (Nagybánya) and in particular of the paintings of Simon Hollosy (1857-1918) (of whom there is mention in the catalogue).

But more important it is to REFLECT on and see in PERSPECTIVE the Romanian cultural presence in the United Kingdom or rather the quasi-lack of it, or its very modest presence. To give very few examples on exhibitions of other Central and Eastern (former communist block) countries:

* The Czechs and the Poles seem to have been absent for a long time in London for reasons difficult to explain, although their art treasures are quite exceptional in spite of the ravages of the 20th century

* Bulgaria had a dazzling exhibition at the British Museum about The Gold of the Thracians

* Serbia was very much present at the Royal Academy as part of the great “Byzantium” exhibition with several important religious works of art. By contrast Romania which could have contributed so much with the tapestries of the Moldavian monasteries had only ONE item offered by the National History Museum!

Clearly the ‘talibans’ of the Romanian Orthodox church do not see the benefits of Romanian cultural presence abroad – although the monks of Mount Athos or the hierarchy of St Anne’s, from Mount Sinai seem to have taken a more enlightened view!

* The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford did however include a series of archaeological artifacts from Romania in an exhibition which included the Cucuteni Neolithic period including some from Bessarabi and Bulgaria: but this was mostly a specialist exhibition within a narrow niche specialism for historians and archaeologists, rather than of a general public appeal.

* Our Russian overlords are nevertheless more active on the international PR cultural scene, whether in permanent exhibitions from the Hermitage (now sadly closed), from Russian Collections abroad (Diaghiliev costumes at the V & A) or the RA exhibition of Impressionist art.

* Romania was an indirect beneficiary of the Brancusi retrospective at the Tate Modern – but this was not a Romanian initiative, per se, as the exhibits were overwhelmingly from the USA, UK and Western Europe: predictably there was a ‘back-door’ tentative to make a claim to such illustrious exhibition by some Romanian Cultural outfit, which went largely unnoticed even by those visitors who having seen the Brancusi exhibition did NOT absorb the detail of the artist’s Romanianness. Why shall one blame them when even Romania waited the best of a century before it reclaimed the sculptor? The previous important Brancusi retrospective was in Paris, at the Cente Pompidou, in the mid 1990s.

* Romania’s really great cultural presence in Great Britain and in Western Europe was made under the Monarchy of King Carol I and Carol II respectively. After the vagaries of a XX century Europe in turmoil and the advent of the dictatorship which created a near embargo on artistic exchanges (other than folk dancing and the odd opera singer or ballerina who took the opportunity to defect) Romania excelled by a long absence from the world cultural scene. This situation could be assigned to several factors but it is mainly due to the destruction of the cultural elites which died under torture in communist prisons or hard labour camps and their replacement by the ‘great unwashed’ – essentially those ‘reliable’ Party officials with no vision, no clue, no desire and no imagination, other the perpetuation of physical and moral abuse, the fudging of History, the destruction of Memory and the shear isolationism (other than in sport). After the so-called ‘1989 revolution’ which put down the dictator and his wife – the second echelons of the Communist Party swiftly filled in the gap and the trend of deculturalisation or the leveling by the lowest denominator was carried out at a national scale. Currently the greatest attraction of those governing the country are the rewards of corruption and wild Capitalism, where everything goes. This phenomenon is responsible for the paltry attempts at putting the country on the Cultural map of Europe and the World. The practice by the infamous “Institutul Cultural Roman” in Bucharest at spending huge amounts of money in organizing exhibitions in rural France, in villages that nobody heard about, really beggars belief! Why not in Paris or Lyon? Such inept locations of obscure villages may have as only excuse that nothing was thought or planned in advance and that the major funds were instead diverted towards such extraordinary feats as publishing the French translation of the PhD thesis of some former Foreign Minster: his summum of philosophical wisdom of some 40 years past: this was printed by an obscure Parisian publisher who subsequently sold the whole edition to the Romanian Cultural Institute – just as it was the practice before the ‘revolution’ with the works of Ceausescu and his wannaby ‘scientist’ wife.

Tell us what has changed?

One could go on with a long litany of half-cock attempts by Romanian officials under the guise of signal ‘achievements’ which now they crow about from the rooftops of Romanian government buildings, events which pass completely unnoticed there where it matters.

We have it from a reliable source in London that attempts were made in the second half on the 1990s by some Romanian exiles to initiate a prestigious exhibition iof the Post-Byzantine Orthodox tapestries of Moldavia. To this end a Minister of State was expedited to London to meet its British Counterpart. The latter who combined on his watch Sports with Art (oh, yes, under Labour anything was possible, including putting once’s foot in the mouth… ) offered as a venue Kenwood House, a country house in Hampstead, some 16 Kms from Central London, in NW6… Not only the venue was geographical eccentric and inconvenient to be visited by the greater public, but the space was in an ORANGERY (!!!), where such ancient treasures would have been damaged by sunshine, humidity and temperature variations …

On hearing about the British proposal, (made in the best faith by a politico who had no clue, to his Romanian colleague who matched his ignorance), the Romanian who initiated the consultative meeting in London and who was a resident in Britain for many years exclaimed to the visiting Romanian Secretary of State:

“But (the British Secretary of State) talks through his hat!”.

As the Romanian sense of hierarchy always required an inevitable kowtowing, such remark caused consternation, although it was made in private after the official meeting ended:

“Vai Domnule, cum puteti spune asa ceva? Un ministru nu vorbeste prin palarie!”

“Pray, Mister, how can you say such a thing? a Minister never talks through his hat!”

Of course there was no need to bother with further explanations which will have fallen on deaf ears. Still the Romanian cultural komissar was offered generous logistics PR assistance in London, including the promise of sponsorship by international private banks: all in vain as the visiting Minister switched off completely! Predictably the ‘official’ visit to London never went beyond its tourist attraction and the project was still-born through lack of follow-up; quite typical, but not surprising:

Think small comrades and carry on navel-gazing – we are and we shall remain the ‘best and most talented Nation in Europe’, regardless of our failures and inadequacies!

But maybe ‘thinking Hungarian’ is not such a bad thing, after all, think Central London and allow for a five-year plan, which for ex-commies it should not be so difficult – it is like home from home!

Inca odata se vede ca in dec.89 a fost o rotire de cadre: Patapievici e urmasul celor care de la Kremlin de unde luasera porunca s-au dus in Suedia sa-l torpileze pe Blaga la Premiul Nobel.

Credeti ca Patibularului nu i-a spus nimeni ca in 2010 s-au implinit 120 de ani de la nasterea Olgai Greceanu, 100 de la nasterea lui Ion Tuculescu si a Zoei Baicoianu?