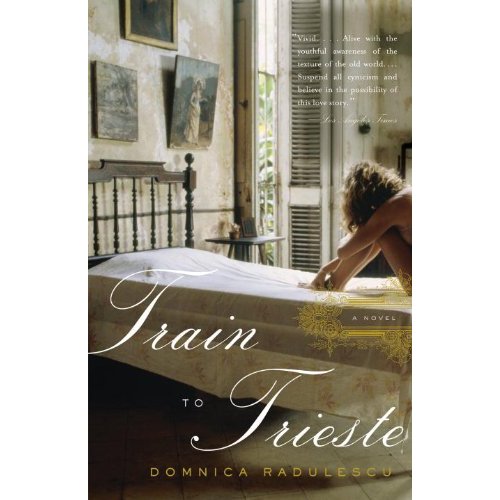

‘Train to Trieste’

by Domnica Radulescu

Life under Ceausescu was not a piece of cake!

We learn from Domnica Radulescu, a Romanian Academic naturalised US citizen, or rather, through the narrative of the central character of her novel – one Mona Maria Manoliu, that life under Nicolae Ceausescu was not a piece of cake. So far – not much of a surprise, as this is a generally accepted truism.

All things being equal, one may well ask who might be interested in Romania, when a handful of established stereotypes would suffice?

‘Train to Trieste’ is set to dispel such reductive exercise: its very title evokes the Continent’s soft underbelly which always represented a porous border between two very different European worlds: North vs. South and East vs. West. First the Habsburg Empire, in the North pushing for access to the Mediterranean South : this made Trieste a cosmopolitan nexus where Italians, Croats, Austrians, Greeks coexisted. It was an enchanting city where James Joyce lived before WWI, the very creuzet which produced this author’s seminal writing, although the great Irishman conceded:

For myself, I always write about Dublin, because if I can get to the heart of Dublin I can get to the heart of all the cities of the world. In the particular is contained the universal.

Domnica Radulescu would certainly not disagree with the Joycean concept. This is because, after the Second World War, as Europe was divided by an Iron Curtain, Trieste’s attraction resided in its permeable border control which drip-fed a steady trickle of refugees from the East of Europe seeking the mirage of freedom in the West. Here the loop closes, as the analogy with James Joyce becomes apparent.

Romanian-born Domnica Radulescu, Professor of Romance Languages and Gender Studies, USA, author of "Train to Trieste"

Like James Joyce, in Trieste, who turned to his familiar Dublin as inspiration and moral sustenance, so did Domnica Radulescu‘s ‘Train to Trieste” got its spirit and stamina from the cities where its author lived and loved in Romania, from its mountains and scent of fir trees or linden trees in bloom, from its family dramas and above all from the fear of an oppressive regime, embodied by the ubiquitous secret service agents, their informers and victims. These images are all entwined in a central thread of a social and political tapestry. The reader will soon discover the first part of the book being set in Romania, yet all along the second half, as the story moves to Chicago, there are constant flash-backs to episodes and shreds of life left behind in the character’s native land.

One may get the impression that such construct would inevitably make for a melancholy reading: not in the least – although we come across many dark episodes of a life of misery and fear under dictatorship, the style throughout the narrative keeps an alert and spirited pace, coloured by exhilarating thoughts of a little girl, whose life we follow, as she turns into a seductively mercurial and irrrepressively oversexed woman, with a great joie de vivre. To the Anglo-Saxon reader, unaccustomed to the flowery Romanian language, charged with hyperboles, the style of the book may appear somewhat contrived. However, for those of us more familiar with this corner of Europe, quite the contrary, the style of Domnica Radulescu captures perfectly well the Romanian ethos. This is not just a riveting fiction, it is an induction course in Political and Social History of life under Communism, two books for the price of one, yet constructed skilfully, in perfect harmony with each other.

During the 20th century many Romanian exiles made France or Germany their adoptive country, although some settled elsewhere in the world. But those Romanians who wrote in French or German were little translated in English and indeed still fewer of them wrote in English. Before WWII we can think of Helen Vacaresco, Countess Anna de Noailles, Princess Bibesco, or Panait Istrati, all of whom wrote in French. After the war, exile novelists Virgil Gheorghiu, Mircea Eliade, Vintilă Horia, Emil Cioran, Gregor von Rezzori, Herta Muller wrote in Romanian, French or German respectively. Nevertheless few of their titles were rendered in English and amongst the latter fewer still became bestsellers, or enjoyed the accolade of an International Prize, with a few exceptions, just!*.

Although the division of Europe, after WWII, fractured the natural links and flow of ideas between East and West, this did not prevent the Czechs to produce a Kundera, the Poles Wislawa Szymborska, or indeed the Albanians Ismail Kadere. By contrast, the spotlight of international recognition of East European writers has generally bypassed Romania, leaving her literature in the shadows. This lapse could not be assigned only to the paucity of translation alone, but primarily to the absence of a broader, less parochial perspective of a Romanian fiction which did not sever its umbilical chord from Nicolae Ceausescu‘s obsessions or indeed with the glorified, wooden language stereotypes of Marxist speak.

By contrast, Domnica Radulescu, is a breeze of fresh air. Forget the pretense of her Mioritic co-nationals, left behind in their back water, lamenting their lack of international recognition and blaming it for using a ‘little-spoken language’! Twenty years after the fall of Communism they have not yet woken up from their lethargy – their overblown egos of big fish in a small pond remain stunted and unconvincing! Had Domnica Radulescu been left behind in the Balkans, one may well ask what might have been left of her free spirit? one would rather not surmise!

One thing is absolutely plain and the writing is on the wall for all to see – the official dictum from Bucharest, through its ‘cultural’ mouthpiece, the Institutul Cultural Roman, is that all Romanians who write in a foreign language do not belong to the “true” Fold of Romanian Literature (!) Unsurprisingly, this is exactly the same indictment pronounced sixty years ago by the ‘High Priest’ of History of Literature, under Gheorghiu-Dej (Nicolae Ceausescu‘s predecessor), one George Calinescu. who dismissed the oeuvre of Romanian exiles in Paris as being ‘unpatriotic’ (sic) because it was written in a foreign tongue! (Calinescu, op. cit History of Romanian Literature, UNESCO and Dragan Publishing, Paris, 1987). Ironically, today, twenty years after Ceausescu was put down in a classic coup de palais, the Romanian Academy’s own Institute of History of Romanian Literature is still named after George Calinescu – the dictatorship’s own Court jester, whilst the attitude towards exile writers has remained hostile. Even as far back as the end of the 19th century Helene Vacarescu was crticised in Romania for “not being worthy of her ancestors” because she lived in Paris where her French debut in poetry enjoyed a great success…Her poem “The Soldier’s tent” was put to music by Sir Hubert Parry to become a popular patriotic song in the British Army fighting the Boer War… Queen Victoria was much impressed by the young Romanian poetess who was lionised in Paris, but not in her native land.

Away from this maddening crowd, in the United States, Ms Radulescu has made her reputation as an Academic, rather than a fiction writer, as she is only at her second novel. Yet the omens look good: be true to yourself Ms Radulescu and resist being distracted by mermaid songs! We are looking forward to your next novels.

Watch this space!

—————————————————-

*) in 1903 Princess Marthe Bibesco received from the Académie française a literary Prize for ‘Huit Paradis’,

Countess Anna de Noailles was the first woman elected to the ‘Académie royale de langue et de littérature françaises de Belgique’.

In 1949 Virgil Gheorghiu‘s ‘The Twenty-fifth Hour’ was made into a film of great success,

Vintila Horia‘s ‘God was born in Exile‘ was nominated in 1960 for the French Goncourt Prize in 1960 but both writers Gheorghiu and Vintila became the target of a witch hunt by the French Left, inspired by the Romanian Securitate.

Eugene Ionesco‘s plays ‘The Bald Primadonna’, ‘The Lesson’ and ‘The Chairs’ marked the birth of the ‘Theatre of the Abusrd’ and was elected to the French Academy,

Mircea Eliade was elected to Académie royale de langue et de littérature françaises de Belgique,

Both Anna de Noailles and Helene Vacaresco bear the name of two literary Prizes in France.

No Comments so far ↓

Like gas stations in rural Texas after 10 pm, comments are closed.