Vera Maria Atkins (née Vera-May Rosenberg)

b. 15 June 1908, Galati, Romania– d. 24 June 2000, Hastings, England)

WWII Secret Service Agent, SOE, Squadron Leader of the Women Auxiliary Forces (WAAF),

Croix de Guerre, Commandeur of the Légion d’Honneur (1987)

BIOGRAPHY:

Vera Maria Rosenberg was born in Galati, the only daughter of Max Rosenberg a well-to-do Jewish businessman from Germany. Max settled in Romania at the beginning of the 20th century to manage his brothers’ shipping business in Galati and Constanta. Vera’s mother, Hilda Atkins was born in London. Max and Hilda met in South Africa where Hilda’s father Henry Atkins, made his fortune during the Boer War by supplying the British Army with porridge and tinned meat from Australia which he had the foresight to stockpile before the war in huge quantities. The Atkins business interests in South Africa flourished to diversify into building a booming Cape Town and also in acquiring a diamond mine. If the Boer war turned out to be a bonanza for the Atkins it was certainly an economic disaster for the business interests of Rosenberg. The downturn of Rosenberg’s business fortune did not preclude Max from marrying Atkins’ daughter Hilda, as they exchanged vows at the London Central Synagogue in 1902. Thereafter Max was compelled to sell at a loss his South African assets and move instead to Romania. Why Romania of all places? Because the small Balkan kingdom which became independent from the Ottomans only twenty years previously was experiencing an unprecedented boom marked by a huge economic growth. The Danube was its main export thoroughfare to central Europe and to the Black Sea for such commodities as timber, cereals, livestock and petrol from the country’s refineries.

Galati – Vera’s birthplace and self-denial:

Galati port on the Lower Danube, in Romania, where Vera's family made its fortune (Period woodcut, private collection, London)

The International Danube Commission was regulating the passage of foreign ships and Britain had its own representative there as well as a Consul at Galati. By 1890s Galati was a thriving port where foreign traders were trying to gain a slice of the profits by exporting Romania’s riches. The port of Galati was of sufficient interest for the British to have there a Consul since before the Crimean War. Perhaps one of the most distinguished British envoys was one Charles George Gordon ( 1833-1885) before he made his reputation in Sudan as “Gordon of Khartoum”. At Galati Gordon was involved in the International Danube Commission: his opinions on the inter-ethnic relations during the mid 19th century is revealing especially as they reflect the official Imperial attitude to such outposts of Europe (Thompson: 137).

Charles George Gordon, CB (1833-1885), British Consul at Galatz, before he became known as :'Gordon of Khartoum'.

By 1904 when Max Rosenberg came to Galati where the German Gebrueder Rosenberg of Cologne had shipping interests: they were exporting timber from their estates in the Carpathians on the fringes of Austria-Hungary. The city had no less than eighteen synagogues for its sizable Jewish community of some 20,000 souls. Romania was for Vera’s father, Max Rosenberg a land of opportunity where he restored his personal fortune to become a powerful businessman with a shipyard at Galatz and a merchant fleet on the Danube, the Dunarea company registered in London. With success came money and with money came acceptance: Rosenberg was entertaining foreign diplomats at shooting parties on his estate at Crasna, in Bukovina, or at his brother’s estate at Valea Izului.

In spite of this comfortable “colonial” life style Hilda’s mother did not settle well in Romania as she was constantly pining for her more sophisticated life in London and for the climate and scenery of South Africa. According to Vera’s hagiographer Sarah Helm, Vera, like her mother, appeared to have regretted her father’s choice of coming to Romania, in spite of the family’s financial gain which brought it considerable wealth. Romania secured for Rosenberg the foundation on which Vera enjoyed a favourable handicap in life which secured for her the best education open to daughters of Europe’s upper classes to private schools in Switzerland, France and England and earlier on with foreign governesses in Romania.

However on a deeper reflection, there maybe a strong case against including Vera Rosenberg Atkins in an Anthology of Romanian Women, simply because her Romanian roots, per se, were not tenuous and in particular she appeared to identify herself more with her mother’s British heritage, rather than her father’s Romanian aspirations. Yet Max, whom Vera adored had a more pragmatic approach than the South African Hilda: Max was feeling at home wherever the going was good and business prosperous and in the 1900s this happened to have been on the Danube and in the Carpathians.

It is true that Vera had cosmopolitan roots and aspirations were reflected in a commensurately cosmopolitan upbringing. But her Romanian beginnings were going to leave an indelible mark on her personality, although later on in her adult life she tried to deny them and even erase them from her memory. Such self-denial did not just apply to her Romanian birthplace but also to her Jewishness. Hers was not an isolated phenomenon, by any means: King Carol II Jewish mistress Madame Lupescu was such an example, or the movie actress Nadia Gray, coming from a historic Romanian family the Herescu also airbrushed her Romanian roots in favour of he maternal Russian, origins. On the other hand Vera’s self-denial and fixation in playing down her Romanian background was consistent with her family tradition which for generations put a smoke screen over its more humble origins. These were the Etkens, her maternal folk, who fled the pogroms of Bielorussia, during the 19th century, to settle in South Africa and change their name to Atkins. Similarly Rosenberg’s own German Jewish origins from Kassel were presented as plain ‘German’ and to prove it Max was busy erecting a catholic chapel on his estate in the Carpathians, a pious feat for which the Pope sent him a medal. Given the prevailing anti-Semitism of 19th century Europe, these adaptations were necessary but in addition they had an overprint which was exacerbated by a certain snobbery amongst the Jews themselves – theirs was a strong preconception whereby German or English origins were ‘superior’ to the East European roots. One can see how Max and Hilda Rosenberg passed on to Vera these prejudices to which they were applying an additional more attractive gloss, in order to attain social kudos.

Max died in 1933 in Romania and Vera who was going to be naturalised British in the 1930s adopted her mother’s maiden name and subsequently considered her birth in Galati as a mere ‘accident of history’ dictated by her father’s commercial interests. Whether coincidentally or not the Romanian youth of this young lady remained an important component in the makeup of her personality and her future professional career.

The Romanian component:

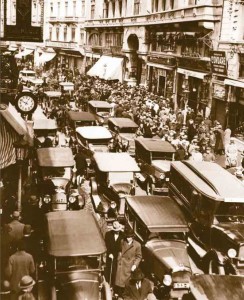

Bucharest in the 1930s dubbed "le Petit Paris" it had a buoyant social and economic life. Here Vera Atkins escorted Count for Schulenburg.

The source of our interest in Vera’s Romanian biography is twofold – first because it sheds light on 20th century Romania from 1900 to the Second World War and in particular on the playground of upper class Jewish community there, which was a world apart from the lower class immigrant Jews inhabiting the same towns and schtetles. Secondly because Vera’s glitzy life in the Bucharest of the late 1920s and early 1930s was crucial in moulding her future career as a spy in the services of the SOE during WWII. This was the backdrop of a world which faded into history, a world so fondly recalled by Clara Haskill and so vividly portrayed by Gregor von Rezzori in his memoirs. But above all it was the world frequented by the diplomat and writer Paul Morand, the gay life of a sophisticated Petit Paris, described by Satcheverell Sitwell and Queen Marie of Romania. For Vera’s knowledge of languages including fluent English French, Romanian, German was common place among aristocratic families of Bucharest and this enabled her establishing a good social network and make her an effective communicator.

Count von Schulenburg (1875-1944), German Ambassador to Bucharest and friend of Vera Atkins: he was shot in 1944 following an aborted assassination plot against the Fuehrer

Count Friedrich von Schulenburg (1875-1944) the German Ambassador to Romania enjoyed Vera’s company as the young woman threw herself into the glitzy social whirl of Bucharest. Later Schulenberg was going to be instrumental in forging the ‘German-Soviet Non-aggression Pact’ and the annexation of Romanian territory by the Soviets in 1940. In 1944 Count Schulenburg was hung by Hitler for his implication in a plot against the Fuehrer. But in the early 1930s when the Count was Ambassador in Bucharest this was yet a good corner of Europe to live in. For Vera the easy-going atmosphere of laissez-faire Romania was infinitely more attractive for a young debutante girl than the more rigid principles of the British society at the Court of St James’s during the reign of George V and his staid spouse Queen Mary, Princess of Teck. Vera’s pragmatic father knew it too well for he gained automatic acceptance in the Romanian high society where he created for himself the life of a country squire on his estate in the Carpathians. In Romania Rosenberg enjoyed the luxuries of a ‘colonial life’ style, affording large houses and soft-footed servants, all more affordable than in Britain. Here it was easier for a foreign businessman to host a shoot of Carpathian bear or wild boar than stalking deer or shooting grouse in the Scottish Highlands.

Vera Atkins Biography "Spymistress" by William Stevenson

Maybe the answer to this option taken by Max came from Sarah Helm herself, Vera’s biographer, pointing out that the Jewish upper classes in Romania were accepted – as opposed to their lower class co-nationals, who were poles apart and had little to do if anything with each other. So much for the Rosenberg’s social history against the 20th century Romanian backdrop.

Out of Romania:

In 1933, after her father’s death, Vera emigrated with her mother to England, but soon after they settled in France during the Socialist presidency of Léon Blum. This was an inspired move because elsewhere in Central Europe the Rosenberg cousins who stayed behind in Czechoslovakia were rounded up and sent to Auschwitz . One of Vera’s cousins, Walter Rosenberg (aka Rudolf Vrba, 1924-2006) became famous for escaping in April 1944 from the concentration camp. His statement known is history as the Vrba-Weltzer Report was to be the first source in informing the Allies about the methods of extermination details of which were reported by the BBC. This prompted world leaders to appeal to the Hungarian dictator Horthy to halt the deportation of Hungarian Jews to the gas chambers. For a while some of the Central European Jews benefited from a temporary reprieve, and were allowed a quick exit from the quagmire. In this context Romania represented a secure transit on the way to Palestine and the future state of Israel, although the British Foreign Office was none too happy about such influx of immigrants and advised the Romanian Government to stop it. After 1945 it was the turn of the Soviet occupation authorities to refuse giving exit visas to the ethnic Jews of Eastern Europe wanting to migrate to Israel.

Before the German occupation of France Vera enrolled as a student in modern languages at the Sorbonne, followed by one-year course at a finishing school in Lausanne, a privileged education in an incubator reserved for young ladies of upper class families. This background was going to keep her in good stead as an intelligence operative during WWII, a role defined by Ian Fleming in his classic retort:

In the world of spies, Vera Atkins was the boss.

Ian Fleming (1908-1964) who created Miss Monneypenny after Vera Atkins.

But occupied France was not the best place for an uprooted Jewish family and in 1940 Vera returned to England, where her career as an SOE operative took off under Maurice Buckmaster (1902-1992). During her time as an SOE officer the indomitable Atkins sent 470 agents including 39 women behind enemy lines into German-occupied French territory. Her spying persona inspired film makers as she became Miss Moneypenny in a James Bond movie and also the main character in Genevieve Simms movie Into the Dark.

Still the great paradox in Vera Atkins’ life remains the contradiction in offsetting the effect of Romanian anti-Semitism versus the brand practiced in France or Great Britain, three countries where she lived and where she enjoyed a very different social life and acceptance! Vera Atkins distanced herself from her native Romania where she enjoyed the spoils of her family riches, frequented the high society, was accepted, had fun and was safe. Her example is not singular, yet in spite of it Romania remains to this day a fair game for western historians censoring her for her treatment of ethnic minorities. Surprisingly, in the same breath, the said academics seem to be incapable of discerning a more nuanced reality from a blanket stereotype: indeed, Vera’s family’s wealth and lifestyle seem to contradict the said effects of Romania’s brand of nationalism.

By contrast in France, where anti-Semitism was rampant, this was an infinitely less safe place for Jews to live in, as they were sent in droves to concentration camps, which was the case everywhere in Central Europe, as reported by Vera’s cousin in the famous Vrba-Weltzer Report broadcast by the BBC. In England the brand of anti-Semitism was more covert than in France or Romania, but persistent enough not to cause Atkins to be given the recognition she pined for: even many years after the end of WWII she never received even as little as an OBE for her war-time services: of course, she was too stiff-upper lip to show her discomfiture! Still, some four decades after the end of war, in 1987, Atkins received instead from the French president the Croix de Guerre, Commandeur of the Légion d’Honneur.

Vera Atkins died quietly, aged 92, in a home for the elderly in Hastings, in Southern England.

Vera ATKINS (b Galati , Romania, 1908 – d. Hastings, England, 2000)

A biography from the Anthology:

Blouse Roumaine – the Unsung Voices of Romanian Women

Dear Sir or Madam,

Detail from this article have helped us formulate information which will be used to establish the Vera Atkins Memorial Seat to be situated in the Special Operations garden of the Allied Special Forces Grove within the National Memorial Arboretum, Alrewas, Staffordshire.

Details of the seat are available from our website.

Hope that this is off interest and we welcome any contributions toward the memorial.

Regards,

Mike Colton

Secretary

Allied Special Forces Association

P.O. Box 32, Hereford, HR1 9DF

You have incorrectly labelled the illustration of “Spymistress” as a biography of Vera Atkins “by Sarah Helms”. Clearly the author is William Stevenson.

Dear Spencer de Vere,

Re: “Vera Atkins – a Romanian Matahari in the services of SOE” – extract from “Blouse Roumaine the Unsung Voices of Romanian Women” reprinted by the Centre for Romanian Studies

Thank you for your communication regarding the above: this is to confirm that we have now amended the label to the Illustration of “Spymistress” as pointed out by you: we are grateful for mentioning this error which is now corrected.

Kind regards

Editor

London

We are taking the opportunity that Blouse Roumaine contains biographies of many other female contemporaries of Vera Atklins who were of Jewish extraction and/or worked in the Secret Services during the war on the side of the Allies, or indeed Romanian women who helped the ethnic minorities from avoiding being deported to concentration camps amongst the latter figures the late Queen Mother of Romania who is remembered at the Vad Yashem Mrmorial.

http://www.blouseroumaine.com/buy-the-book/index.html

To Mr M Colton,

Secretary

Allied Special Forces Association

May I humbly request that you watch the programme “Secret War: The Spymistress and the French Fiasco”.

You may find that not many people will wish to contribute to a memorial seat for a woman who sent over 100 agents to their deaths because of her and her boss’s ineptitude.

After reading Stevenson’s book about her efforts during the war of the heads of England’s main secret service to undermine her and after the war her efforts track down those responsible for those 100 agents deathsin Germany. Were those agents discovered and killed thru her ineptitude or thru those made by the heads of the SIS. or more specifically people like Kim Philby? just curious.

This editor is welcoming the dialogue elicited by this article. In the above context the author’s intention was to reflect Vera Atkins’ ambiguity vis-a-vis her Romanian past and in particular the contradiction therein. In the editor’s opinion, given the prevailing misconceptions on Romanian society to WWII, it was important to shed further light on this abstruse aspect of Vera’s background during her formative years. In this context we welcome the questions raised by this article.

Count von Schulenburg (1875-1944), was German Ambassador in Moscow not to Bucharest.

Count von Schulenburg was indeed, as you say, Ambassador to Moscow, but before this period HE WAS German Ambassador to Bucharest, as seen in his career history below:

Political career

Vice Consul to Barcelona, Spain (1903)

Various Consulates to Lemberg, Prague, Warsaw from 1903 to 1911

Consul to Tiflis, present-day Georgia (1911-1914)

Consul to Beirut, Ottoman Empire (1922-1924)

German ambassador to Teheran, Persia (1924-1928)

German ambassador to Bucharest, Romania (1928-1931)

German ambassador to Moscow, Russia (1931-1934)

State Secretary for Foreign Affairs (1934-…)

Just to say to Mike Boyd I think that you will find it was Maurice Buckmaster’s incompetence that led to the death of many of the agents. Vera Atkins did not make decisions on whether agents were ‘blown’ or not and she cared deeply about their welfare.

Very interesting to read of this courageous lady. I have the book Spymistress. rgds Greg.

My name is Peter Rosenberg my Father’s name was Fritz R. We lived in Valea Uzului before the war.

Peter was born just before the World War 2 in Eastbourne UK and came back to Romania.

The Spymistress Vera Atkins was my aunt. I also met her in London 1967-68 when I attended The Imperial College in London.

Any information on my family Rosenberg is appreciated.

Sincerely Peter

Domnule Rosenberg,

Thank you for your communication. Unfortunately I never met your Aunt and her fascinating life I gleaned from her posthumous biography: sorry not being able to furnish you with further information. Wishing you luck in your further research.

Kind regards,

Editor

During the war when we lived in Palestine from 1940 to 1948 my Fritz was trained by British and worked in Palestine then Cyprus it goes on and on.

We got to the UK to live at the Earl of Yarborough in Lincolnshire Fritz worked as a clerk. We left in 1950 by the Queen of ?? thinking landed in New Brunwick train to Montreal became our home

Peter Rosenberg

Cher Monsieur Rosenberg,

J’aimerais entrer en contact avec vous pour vous poser quelques questions au sujet de vos parents, Arthur et Nina Rosenberg.

Je suis historien et travaille pour les Archives Vladimir Ghika de Bucarest.

Bien à vous,

Luc Verly

My Great Grandfather Henry Atkins emigrated from Europe to South Africa in the late 1800’s. His daughter Hilda Atkins married Max Rosenberg, the parents of Vera Atkins.

Henry’s son Arthur Atkins (my Grandfather) married Hilda Cross (a curious repeat of the name Hilda) in South Africa. She was descended from 1820 settler stock and the family were originally Irish. I was told that Arthur converted to Christianity at some point. He and Hilda had three children, Dennis, Patricia (my mother) and Diana.

Diana went to the same finishing school in Lausanne as did Vera many years before.

My mother came to England in the early 1930’s, met my father ‘Bob’ Dresser and married him only weeks later. I was born in Weybridge, Surrey in 1936.

My parents and I emigrated to South Africa in 1946. I was educated at Michaelhouse in Natal, where my uncle Dennis (the only South African to be awarded the George Medal for civilian gallantry) had been at school years before.

I returned to England for five years, when Vera, whom I met many times over the years, encouraged me with my writing. I visited May Mendl a few times at her her house in Winchelsea and I briefly met Guy Atkins before I returned to South Africa in 1959 until 2013 when my wife Hero and I relocated to the UK.

Thanks to Sarah Helms book on Vera I have learned for the first time details of Vera’s early life and how we are related, that I was unable to discover from Vera.