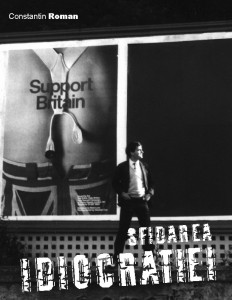

“Defying the Idiocracy”

Constantin ROMAN

SYNOPSIS

The world from which Constantin ROMAN emerges, is blurring gently through the lens of time. Once landed on the British Isles, the faraway country which he left behind is thoroughly destroyed by the bulldozers of Ceausescu’s cultural revolution and its ruins remain behind hostile frontiers.

Being shipwrecked on a foreign shore should not be in itself a novel occurrence for a Romanian whose ancestors were too often compelled to cross the insecure borders of the principalities of Wallachia, Moldavia or Transylvania in search of a peaceful haven: because such uprooting was not the outcome of some impulse, it was rather the result of an unexpected conjecture, dictated by unforeseen circumstances.

The patriarchal and quietly sedate neighbourhood where he spent his childhood in Bucharest, the capital of Romania was soon going to be sealed by political events which followed the second world war and would jettison the beginning of his life: this was his parents home secluded in a garden with lime trees in bloom, at the foot of the Orthodox Cathedral Hill. Round the family table the conversation would often revolve around the literary prizes in Paris, or the Cannes Film Festival. In the grandparents home, furnished in Louis XVI style and decorated with Savonnerie tapestries, the family will gather every Sunday afternoon, for tea and then, around the Steinway grand piano, to listen to Chopin nocturnes and Brahms sonatas. The ‘fin de siecle’ paintings hanging on the walls would display the voluptuous bosoms of ingénue gypsy flower girls. The endless rows of bookshelves in the library had, on closer scrutiny volumes mostly in French, followed by German books printed in old Gothic script, interspersed with some titles in a few other languages. Likewise, the voices which were overheard in the household would converse mostly in French, pronounced with that guttural “r” consonant, which would roll strongly against the palate, in a typical Romanian fashion. French was the language of grown-ups, when trying to keep secrets away from children, who would otherwise speak German to their nannies from Transylvania. In the kitchen the cooks would speak Hungarian and the rest of the household servants would speak Romanian.

There were always extravagant tales from the twilight of the XIXth century, whose echo reached even Queen Victoria, who, on receiving news of the betrothal of her preferred granddaughter Missy to prince Ferdinand of Hohenzollern, heir to the Romanian throne exclaimed in dismay: “ the country is unstable and the morality of the society in Bucharest quite unbelievable!”

Following the diplomatic horse trading at Yalta and Teheran, the political events started to unfold at great speed and so the conversation at table, even more than the reminiscences of yore, the art exhibitions, music or science would start to be dominated by the politics of the Great Powers and their sphere of influence, before the talk would be reduced to mere existentialist topics about the scarcity of food, buying of meat on the black market, queuing for milk and bread, indeed, about sheer survival. Before long the voices would barely whisper about friends who were arrested in the street, on the way home, or in the dead of night and sent to prisons and labour camps. In the end a complete and deep silence would take over in a dignified and implied disappointment that the “Americans did not come to our aid” (Nu au mai venit Americanii), which was the ultimate hope at shaking off the communist dictatorship, imposed by Stalin’s commissars, through fraudulent elections and the presence of their occupying armies.

By the mid 1950’s one was still be hoping in this surreal scenario, that is of military help from the West, as we were heartened by the Berlin uprising of 1953 and the Hungarian Revolution of 1956: these popular revolts were both quelled mercilessly in a blood bath, without as such as the West lifting a finger. It became painfully clear that the Soviets were masters of their own backyard and were determined to remain so for a considerable time: we felt that we were betrayed and that consequently we were entirely on our own.

Looking back at those times prior to the advent of the Marxist dictatorship, although they are only a few decades apart from the period of his childhood it is still possible to fathom the charm, intelligence and bubbly whit of the Bucharest society conversations, which would be hard to match today. This was a society that was soon going to vanish forever and during his initiation in his exile years and especially that this world was no more Constantin Roman felt for it a deep attachment, because it was the very world, which nurtured him.

Understandably, during these very decades which elapsed, the family lived through political trials and witch hunts, which it could not foresee and it was to be expected that certain permutations and adaptations should take place in the life of the author before he uprooted himself. Such adaptations had inevitable consequences to bear on him, which on a first analysis may have appeared to be contradictory, yet at a closer scrutiny they were perfectly harmonious and even directly conjugate.

In the first chapter of the book he tells us that he aspired to have access to a “renaissance education”, by this meaning that he was dreaming of experiencing those emotions and initiations stemming from an all-embracing European culture whose severed roots he was hoping to restore. Such dreams were not without foundation because since he was a young man he was fed on a staple diet of Vitruvius, Giorgio Vassari and later on Bannister Fletcher. Yet unavoidably and in parallel he was exposed to a Marxist indoctrination, which was compulsory in the state schools behind the iron curtain. To counteract this, during his formative years, his parents took care to give him private tuition in foreign languages, as an “insurance policy”: this opened new perspectives which in the end were going to prove a passport to freedom.

And so, because of the political and social hyperboles of life in post war Romania, Constantin ROMAN was compelled to take on the career of a geophysicist, while he strived since he was a child to prepare himself to become an architect. More precisely his access to a career in arts or humanities was barred by the communist establishment through the positive political discrimination dictated by strict social criteria: he simply was not goood enough material ready be trusted iby the communist regime simply because of his appurtenance to a category branded as being of “unhealthy social origin” (origine sociala nesanatoasa). In order to soften the blow of this political prejudice and in order to secure a higher education, it was decided for young Constantin to follow a science career, rather than one in architecture, whereby he could demonstrate his competence to the admission examiners, based on exact and unique answers of mathematics and physics subjects. This is how he developed into a man of broad culture, in the best tradition of XVIIIth century French intellectuals: his life grew into an endless string of syntheses between romanticism and classicism, physics and poetry, of an orderly living laced with bohemian existentialism, of a conservative heritage overprinted by liberalism. His structured scientific training was altered by a boundless iconoclasm. He experienced a subconscious alchemy of magic and rationality, of dreams intersected by the naked reality. And although such lengthy catalogue of superficially reconciled antitheses is far from being complete, nevertheless, it defines his ethos of a bipolarity similar to that of dyzogotic twins.

At the time when, with a youthful enthusiasm, Constantin Roman left Romania only for a short trip abroad to give a paper at an international conference, he could not anticipate the permanence of this voyage, or indeed the unexpected difficulties which confronted him in the West, stranded with one suitcase, a pack of visiting cards and a five-pound note in his new three-piece suit. For apart from his education this is all he had to his name. In Paris, Professor Thellier of the “Institut de Physique du Globe” offered him to start a doctorate in palaeomagnetism, but in May 1968, the French capital city was not the most conducive place for academic research. To make things worse he was even discouraged to pursue this by the very Romanian Ambassador to UNESCO, who was approached by Roman with the view of assisting him with the extension of the Romanian re-entry visa expired because of a French railway strike. Ambassador Lipatti is better known as the brother of pianist Dinu Lipatti. He did not hesitate to define Roman’s attempt at taking a PhD degree in France as “a political option, which would lead one to become, at best, a waiter in a restaurant”. Stunned by this cynical intransigence, Roman considered the serious implications of returning to Romania with an irregular expired visa, as he might have incurred a permanent ban from ever traveling abroad and even suffer more unpleasant political consequences. As a result of these perspectives he decided rather than returning to Romania to apply instead for scholarships in the West. He was fortunate to obtain against fierce competition a research scholarship from Peterhouse, the oldest Cambridge college, founded in 1284.

This spiritual convergence caused by the superimposing of different cultures had a component stemming from an obdurate youth, coming from an Orwellian-controlled society: yet this element was grafted on a new trunk of Western society and subsequently flowered in the pure and luminous environment of Cambridge, during the stimulating period of the early 1970’s. For this University was going to witness momentous events, punctuated by the students unrest and the women liberation exhortations of Germaine Greer’s “Female Eunuch”.

This spiritual convergence caused by the superimposing of different cultures had a component stemming from an obdurate youth, coming from an Orwellian-controlled society: yet this element was grafted on a new trunk of Western society and subsequently flowered in the pure and luminous environment of Cambridge, during the stimulating period of the early 1970’s. For this University was going to witness momentous events, punctuated by the students unrest and the women liberation exhortations of Germaine Greer’s “Female Eunuch”.

Thankfully this period also coincided with some of the greatest discoveries of Science, which Cambridge ever made in the fields of Astrophysics (Fred Hoyle), of Molecular Biology (Crick and Watson) and the Plate Tectonics (Bullard, Matthews and Vine). The influence, which the creative Cambridge environment had on the thinking of Constantin Roman, is undeniable.

This is because, the Research Scholarship from Peterhouse gave Roman the unique chance of working on Plate Tectonics under Sir Edward Bullard, a physicist whose teaching descended in a direct line through Thompson, Rutherford, Kelvin and Cavendish, all the way from Sir Isaac Newton. Roman’s research under Bullard, offered him an incomparable added value through its original thinking, its capacity of defining the essential and meaningful, its analyses, its extrapolation and surmising scientific truths, its capacity of modifying and redefining core principles.

But above all, his innate curiosity pushed his awareness beyond the limits of Geophysics and of Global Tectonics, as his search grew quickly like a vine intertwining linguistics, history of architecture, physics applied to history of art and archaeology, poetry, journalism and the promoting of Romanian culture.

In time and during many foreign trips to attend international colloquia and conferences, or as guest speaker to British and Continental universities, the cumulative effect of certain impressions, observations, analyses and intuition resulted in the very necessity of modifying Plate Tectonics itself, which made the subject of his PhD dissertation. He felt the need to transform this theory and propose a more coherent concept which should include non-rigid plates, which he called “buffer plates” and at the same time to define as such two new non-rigid lithospheric plates, that of Tibet and Sinkiang respectively, both carved out of the Eurasian plate.

These results were immediately published in academic journals of international circulation and were soon quoted by fellow researchers from the United States to France and China, but not in Romania, where Ceausescu’s censorship implemented a systematic cultural terrorism: the effect of this conspiracy of silence caused this Romanian exile simply to be brushed out in his native country. Surprising as it may appear, even after the fall of the communist dictatorship the same scientific embargo was maintained by the same closed circle of scientists who were the direct beneficiaries of this censorship, in order to maintain their artificial primacy and in particular the claim to have produced the first plate tectonic model for the evolution of the Carpathian seismotectonics. Yet regardless of these minor squirmishes, the concept of non-rigid plates first proposed by this Romanian researcher in Cambridge has been adopted as a classic model in Academia throughout the world.

Looking retrospectively one could state clearly that there is no contradiction in the integration of Romanians and in particular of Constantin Roman within the hegemony of Western thinking, if one considers only a handful of illustrious predecessors who come to mind, starting with the sculptor Constantin Brancusi who is mentioned in the book, but also the philosopher Emil Cioran, the playwright Eugene Ionesco, the Historian of religions Mircea Eliade, the pianist Dinu Lipatti, the composer and violinist Georges Enesco, the novelists Panait Istrati, Virgil Gheorghiu and Marta Bibescu, the poetesses Elena Vacaresco and Anna de Noailles, or the Dadaist Tristan Tzara, who all chose France as their adoptive country. Those few would represent only a fraction among the Romanian exiles in France and the list could go on further, because it is not at all incidental that Romania, much more than any other European country to have a social and intellectual elite infused by the French language and philosophy. And yet, quite the contrary of such tradition here we are witness to yet another dualism, as Constantin Roman does not make France as his natural choice, but prefers instead England as his adoptive country. Here he meets and makes illustrious friends and acquaintances among Masters of Colleges, literary gurus, Scientists, historians, lawyers and power brokers, but also among younger and more humble people of various walks of life: they were all going to become enthusiastic supporters and central field players of the “ Roman cause célèbre”.

At a closer look, perhaps two other contrasts in Roman’s life become less contradictory than at first sight, that is the parallel activity as geophysicist and international expert in oil exploration with that of journalist and impresario: because one knows that before the war the British and American oil industries were active in Romania and it is pleasant to remember that the first poetry translations from French and English, the articles on the history of art and the first contacts with the international critics of Brancusi’s sculpture took place during the time when Constantin was an undergraduate at the institute of Oil Gas and Geology in Bucharest.. Later on, at Cambridge, the Romanian business course, with its statistical linguistic analysis, the translations of Romanian poetry, the articles on Brancusi, the Riemanian art exhibitions in London Newcastle and Cambridge, they were all running concurrently with his scientific research of the seismo-tectonics of the Vrancea and the Hindu Kush mountains which was published in “Nature”, “New Scientist”, The Geophysical Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society’ as well as in his doctorate dissertation “The Seismo-tectonics of the Carpathians and the Central Asia”.

But although and quite happily, such scientific contributions, which were pivotal to the international domain of Plate Tectonics were not completely ignored in the pages of this book, yet the models and the scientific theory which made the scientific reputation of Constantin ROMAN, represent only a small proportion in the whole narrative. In fact they represent only the quintessence of such theories, the author’s autobiography, which reflect the voyages, the adventures the various initiations, the reactions pertaining sometimes to an unfavourable environment, and which, at the beginning, because of his total lack of worldliness he was not capable to understand. And yet, these very different and outright fascinating reactions represent in themselves a singular and perpetually fresh experience.

As events unfold one can follow the author extricating himself from the absurd oppression of a totalitarian regime to reach the pinnacle of a British university. Yet the collision of cultures so much apart is bound to create sparks of a rich and stunning spiritual passion. We follow him further on his numerous trips abroad where he tests his scientific ideas, chases up the girl he falls in love with. But regardless of the aim of these wanderings we realize again the existence of parallel pursuits, as the museums, art galleries and the architectural vistas of cities and cathedrals reveal themselves often reflected under a Romanian angle full of nostalgia. But beyond these places he is interested in people and situations when he describes the reception given at Peterhouse to the British Prime Minister, the garden picnic with the bishop of Ely, whom Constantin addresses as “Your Beatitude” which is the Romanian Orthodox form, or perhaps the feast at Magdalene College, as guest of Robert Latham, the Pepys Librarian, the consultation with Lord Goodman regarding his battles with the British and Romanian red tape, or the evening of Romanian poetry chaired by George Steiner at Churchill College, the dinner at the home of professor L.C. Knights, the great authority on Shakespeare, the meeting with architect Sir Leslie Martin who offers him the chance of organising a photo exhibition of Brancusi’s sculptures, or the initiations in the British contemporary art under the guidance of Jim Ede at his collection at “Kettle’s Yard”, the conversation about Romania with historian Sir Herbert Butterfield and Sir Steven Runciman or with former British ambassador to Moscow Sir Duncan Wilson and Master of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.

But what looms larger by the day, above all these chance encounters and circle of friends is the most important apocalypse – the gradual realization of the impossibility of returning to his home country, now a grisly prison-state. As a corollary of it the imperative of seeking permission to settle in Britain became self-evident.

But to start with such permission was being refused, by the Home Office, because of his student status, which contained by definition specific limitations. From now on we witness the beginning of a campaign supported by the scientific and political elite, which tries to persuade the British authorities to use its statutory discretion and make an exception to the rule. Prominent amongst Roman’s supporters is Lord Goodman legal adviser to the Prime Minister and Government negotiator on Rhodesia. Ironically, and if these complications were not enough, from a totally unexpected quarter, further difficulties pile up, initiated by a prospective mother-in-law, who tries to derail Constantin’s courtship of her daughter.

These are the very fierce battles which the young Romanian had to fight on foreign soil in order to be allowed to lead a normal llife, whether on the personal, or professional front – battles which ended up in as many hard-won victories, reflected in the very title of this book: “Defying the Idyocracy” . For the “idiocracy”- is a new word which the author coined in order to encapsulate the essence of an obtuse if crass bureaucaracy, whose ubiquitous presence he confronted both in the East and the West: this is the idiocracy to which he refused obstinately to conform to and obliged it instead to bend to his own rules and strict principles of universal humanism.

In spite of all this unanticipated purgatory, the book preserves an upbeat style and far from describing an endless inventory of hardships it presents instead the obdurate refusal of accepting them, by circumventing the absurdity of an intractable situation. These clashes of Quixotic dimensions explain the very title of the book – “Defying the Idiocracy”, because of the very daft nature of this battle of wills, between an individual imbued by strong moral values and the establishment of the day, whether in the East or in the West. Yet, as such defiance often turns to comic situations, typical of an Opera Buffa, these artful subterfuges must remain a role model to other hedonists. Because deep down Constantin ROMAN remains a true hedonist: no simple pleasure is spurned and in his relentless pursuit, only gastronomy ranks higher than his passion for science and the arts, because there is no experience that excites the palate, no delicious dish of the gourmet guidebooks, which might have escaped the attention of this Romanian. We are further informed of this predilection, not to call it an obsession of consuming baroque meals beyond the limits of prescribed conventions, which lead inevitably to the failure in obtaining an important position with an international company in The Hague, where he applied for a job…. “Ah”, he says by means of an excuse, “this is the memory of century-old underfed peasant ancestors of the Carpathians.”

Like gastronomy, the refined pleasure which he derives from his unbound exhilaration when admiring the architecture, the gardens and the treasures that surround him represent an enduring background, like a commentary, or a hemicycle on a musical theme, a constant reflection of every movement, an ecstasy which the author is sharing leisurely with the reader, as he turns the pages of this book.

London, May 2006

Further reviews on “Defying the Idiocracy” are posted on:

http://www.constantinroman.com/continentaldrift/

Romanian translation: “Sfidarea Idiocratiei” can be downloaded from the link:

http://www.constantinroman.com/continentaldrift/romaneste/preface.html

No Comments so far ↓

Like gas stations in rural Texas after 10 pm, comments are closed.