Constantin ROMAN: extract din “Continental Drift, Colliding Continents, Converging Cultures”, Institute of Physics Press, Brostol & Philadelphia, 2000 – traducere în limba Română

CRITERII DE DISCRIMINARE.

Prima tentativă de a obţine un paşaport a fost la vârsta de 14 ani, la eliberarea primului meu buletin de identitate, când am crezut că în mod automat eram îndreptăţit să obţin un document de călătorie în străinatate. Pentru că aveam un străbunic ceh, eram nerăbdător sa descopăr familia îndepărtată din Cehoslovacia. Aşa m-am dus la sediul central al Miliţiei Capitalei de pe Calea Victoriei şi m-am trezit într-o încăpere cu o mulţime de oameni în vârstă cu feţe deprimate, dorind sa emigreze în Israel sau America: fiind aşa tânăr am atras imediat atenţia ofiţerului de serviciu, care m-a întrebat ce căutăm acolo. Am spus ca doream un paşaport sa călătoresc la Praga. “Mergi de unul singur?” Pentru a da o pondere mai mare cererii mele, i-am spus că mergeam însoţit de tatăl meu, cu toate ca el habar nu avea de iniţiativa mea. “Bine, atunci roagă-l pe tatăl tău să vină el aici.” Aceasta se întâmpla în 1955, iar eu eram încă un adolescent şi aveam impresia că lumea se prăbuşea în jurul meu. M-am întors acasă năpădit de gânduri sumbre. Mi-am analizat rapid, din interstiţiile memoriei, virtuţile eventuale ale originii noastre sociale, pentru ca să pot avea o ideie de cum m-aş fi putut bucura de libertatea de a călători în străinătate, atâta timp cât paşaportul era acordat doar pe criterii de apartenenţă la o anumită clasă socială şi politică privilegiată: era evident că în familia noastră nu ne-am născut “ilegalişti”. Departe de a aparţine categoriei privilegiate de comunişti nomenclaturişti, familia noastră nu dorea să se compromită luând din mers trenul communist, ba chiar dimpotrivă, după ce ne pierdusem prin expropriere şi naţionalizare toate economiile şi bunurile mobile şi imobile, ajunsesem să fim marginalizaţi. Şansa noastră de supravieţuire nu era foarte bună, să nu mai vorbim de luxul de a fi obţinut un paşaport.

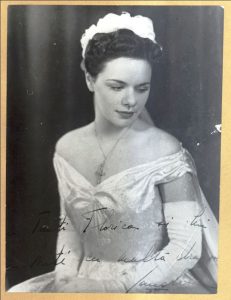

Eugenia Roman, mama mea, la 16 ani. Dupa plecarea mea in Anglia Ceausescu le-a interzis parintilor un pasaport pana cand Margaret Thatcher l-a obligat sa onoreze semnatura lui pe Tratatul dela Helsinki

Mama mea Eugenia (Jeni) Velescu s-a născut în Bucureşti, în 1912 şi provenea dintr-o familie de intelectuali proeminenţi. Ea era cea mai tânără fiică a lui George Velescu şi Ana Zeliska. Tatăl ei, George, licenţiat în Drept şi Farmacie la Universitatea din Bucureşti şi-a ales să profeseze Farmacia, la sfaturile Prea-Fericitului Patriarh Miron Cristea, capul Bisericii Ortodoxe Romane, cu care era prieten. Bunicul meu şi-a început cariera la Farmacia Bruss, din Calea Victoriei, vis-a-vis de Cercul Militar, o clădire de mult dispărută. Bruss, de origine germană era furnizorul de produse farmaceutice a Majestatii Sale Regele Carol I al României. Bunicul adesea prepara reţete pentru Rege, la cererea Şambelanului Curţii, carea venea intotdeauna spunând:

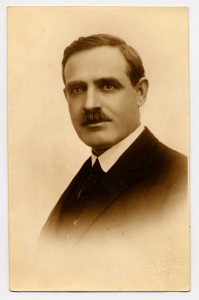

George VELESCU, Presedintele Farmacistilor din Romania (Bunicul matern)reţete pentru Rege, la cererea Şambelanului Curţii, carea venea intotdeauna spunând:

“Tinere, să iei cea mai mare seamă! Această reţetă este pentru o persoană foarte importantă!”

Bunicul, bineînţeles, ştia, în felul acesta, că reţeta era pentru Rege, care l-a decorat, în 1906, pentru serviciile sale. Ulterior, bunicul meu a practicat cu succes farmacia, în cele din urmă ajungând să fie renumit şi sa devină Preşedintele Asociaţiei Farmaciştilor din România, editor al monografiei “Pharmacopaea Română” şi a revistei “Curierului Farmaceutic” din Bucureşti, devenind de asemenea şi unicul distribuitor al produselor farmaceutice Merck din România. Bunica maternă, Ana, se trăgea dintr-o familie Cehă din Bohemia din partea tatălui şi dintr-o familie din Secuime din partea mamei. Această ramură provenea din mica nobilime a Imperiului Hapsburgic, închistată de secole de-a randul pe o scară feudală bine definită, cu titluri si un mod rigid de adresare, care îi defineau précis pozitia ierarhică în societatea transilvană. Născută la Bucureşti, unde a fost educată la şcoala catolică de la

biserica Bărăţia, bunica Ana, sau Grossnutter, asa cum o stiam, vorbea curent trei limbi străine, Franceza, Germana şi Ungara, ea fiind una dintre primele femei din România absolvente (la vioara şi pian) a Conservatorului de Muzică din Bucureşti. In timpul primului război mondial şi-a luat licenţa în Farmacie, ca să poată prelua afacerea soţului ei în timpul în care el era ofiter activ pe front, în Moldova. Fiind copil, îmi amintesc, ca şi cum ar fi fost ieri, impresionanta colecţie de artă şi biblioteca cu cărţi de artă şi biografii politice, în mai multe limbi din casa bunicilor, iar până la venirea comuniştilor, când proprietăţile familiei au fost expropriate, mă duceam la recitalurile de muzică de cameră a bunicii Ana, care se ţineau în fiecare duminică după amiază la casa ei din Bucureşti, din cartierul Mitropoliei. Personalitatea Anei a avut cea mai mare influentă asupra educaţiei mele, întâi pentru că am prins gustul limbilor străine şi de asemenea mi-a deschis interesul pentru artă şi ştiinţe.

Spre deosebire de părinţii ei, Mama mea nu a fost atrasă de partea academică, dar a fost educată să converseze în câteva limbi

Tatăl meu, Valeriu Livovschi Roman, s-a născut în Bucureşti în 1906, ca cel mai mare fiu al lui Vicentiu Livovschi Roman, de profesie farmacist şi a Ştefaniei Burada, singura fiică a Preotului Constantin Burada. Bunicul meu Vicentiu provenea dintr-o familie care a servit Biserica Ortodoxa Română timp de şapte generaţii şi avea o puternică tradiţie muzicală, printre care se numără şi un compozitorul de muzică liturgică rusească si dirijor al corului dela Catedrala Ţarului din St. Petersburg. Compozitiile liturgice ale lui Grigory Lvovski continua si azi să se audă în bisericile ortodoxe. Pe linia bunicii paterne din neamul Burada au fost multi strămoşi preoţi ortodoxi, binefăcători şi ctitori de biserici şi şcoli în secolul al 19-lea, deşi printre ei au fost şi compozitori, judecători, antropologi şi polimati, printre care cel mai proeminent rămane Theodor T. Burada. Tatăl meu Valeriu şi-a luat licenţa în chimie industrială, la Universitatea din Bucureşti în 1930 şi a început cariera în laboratoarele de chimie, a companiei de petrol Anglo-Romane Phoenix, ce avea câmpuri petroliere in valea Pahovei, o rafinărie la Ploieşti şi doua staţii de export a petrolului, la Constanta şi la Giurgiu. Tata a fost curând promovat în funcţia de Director executiv, responsabil cu exportul de petrol, mai întâi la terminalul Companiei, de la Constanta, şi din 1937 la Giurgiu, unde m-am născut în 1941. Când terminalul din Giurgiu a fost bombardat în 1941, tatăl meu s-a transferat la sediul central din Bucureşti, unde a devenit directorul serviciului de distribuţie şi marketing, până la naţionalizarea companiei, de către comunişti, în 1948, când tatăl meu a fost acuzat de “colabore” cu britanicii. A scăpat de închisorile comuniste numai datorita sprijinului activ al muncitorilor companiei, fiind o persoană foarte populară în rândul lor, aceştia pledând pentru absolvirea lui de presupusa vină sa “colaborator” cu executivul britanic al companiei…. In urma acestor acuzaţii tata a fost concediat şi îmi amintesc, ca până să îşi găsească un nou servici, pentru o perioadă de trei luni, copil fiind, doar de şase ani, căram în fiecare zi, cu sufertaşul, mâncarea gătită de bunica mea, la ea acasă, pentru noi, căci familia nu avea alte resurse de subsistentă, toate economiile si veniturile dela bunurile imobiliare fusesera nationalizate de regimul communist, impus de armata de ocupatie sovietica. După mai mulţi ani ca dispecer în Ministerul Chimiei, funcţie în care vizita frecvent combinatul chimic dela Târnăveni şi uzina “Taninul” din Orăştie, tata şi-a încheiat cariera ca Redactor la Editura Tehnică, din Bucureşti, unde a ieşit la pensie în 1966. Nefiind membru al partidului Comunist, numele lui nu avea voie sa apară nici măcar pe coperta cărţilor ce le edita şi şi-a terminat cariera într-o relativă obscuritate. Totuşi, în ciuda cestei situaţii neprielnice a avut mai multe invenţii care le-a patentat, în domeniul catalizei clorurii de sodiu, în care a scris şi o carte, devenita o referinţă clasică, într-o specialitate foarte restransă.

Între timp situaţia politică şi socială din Europa Centrala şi de Est nu avea să se îmbunătăţească. Cu toate ca după moartea lui Stalin, în 1953, o oarecare destindere a avut loc, perioada în care membrii Comitetului Central al Partidului comunist care erau în guvern şi care fuseseră ‘educaţi’ la Moscova au fost îndepărtaţi – toate nume de tristă amintire pentru istoria noastră – Teohari Georgescu, Vasile Luca şi mai ales Ana Pauker, această Dolores Ibaruri a suferinţelor româneşti. Destinderea politică a fost de scurtă durată, datorita revoluţiei din Ungaria, din 1956, care a cauzat o recrudescenţă împotriva clasei intelectuale şi a “rămăşiţelor burghezo-mosieresti”. Bineînţeles, că şi noi făceam parte din această “rămăşiţă” arheologică…

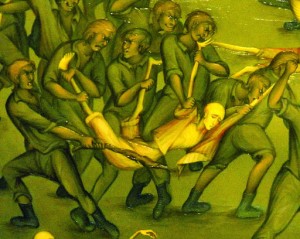

Pentru o clipă, în 1956, când Ungurii s-au răsculat împotriva cizmei sovietice şi a ‘uneltelor’ ei comuniste (pentru a folosi jargonul Marxist), am sperat că vom fi fost şi noi eliberaţi de aceasta oprimare, aşa ca am lăsat-o mai uşor cu studiul limbii ruse, care era obligatoriu la scoală şi aproape că am repetat clasa a cincea. De altfel nu aveam note bune decât la subiectele ale căror profesori îmi plăceau, iar fizica şi geologia nu figurau pe această listă. Geologia era predată de o activistă de partid, care politiza orele, într-un limbaj de lemn. Ea ne-a dezvăluit, literalmente, cum “capitalişti au exploatat zăcămintele de petrol atât de repede încât nu le-au dat posibilitatea zăcămintelor de ţiţei să se regenereze….” “Când?” am întrebat-o eu – “in timpul vieţii noastre?” Nu cred ca înţelesese calamburul, căci altfel aşi fi fost disciplinat.

La vârsta de 15 ani, când devenisem critic asupra tuturor valorilor şi în special al preceptelor comuniste nu puteam să iau în serios geologia predată de o activistă de Partid semidoctă. La examenul de baccalaureat (sau de ‘maturitate”, cum se chema atunci) am trecut geologia la limită. Nici nu mă interesa, pentru că, incă de la vârsta de şapte ani, aveam ideia precisă să devin arhitect, pentru care, aşa consideram eu, geologia nu avea pondere. Revoluţia Ungară din 1956 avea să aibă un efect negativ asupra selecţiei candidaţilor dela Şcoala de Arhitectură, care a început să aplice strict criterii bazate pe origina socială: în anii ’50 se mai vorbea de origine “nesănătoasă”, dar pe la sfârşitul anilor ’60, cum “construirea socialismului făcuse progrese simţitoare” (oh, yes!) acum categorisirea era doar în trei clase sociale, dintre care doar două erau recunoscute ca atare, a treia fiind doar o “pătură”: clasa muncitoare, ţăranii şi pătura intelectuală. Ori si cum fusesem “promovat” fără să-mi fi schimbat genealogia, dela “rămăşiţă”, la “clasă de origine

nesănătoasă”, iar acum de-a dreptul “pătură” pentru că tatăl meu, lucrând cu creierul, mai degrabă decât cu muşchii, era, deci, un intelectual (citeşte pătură). Bine, bine, dar din aceiaşi categorie făceau parte şi copiii “grangurilor” din Comitetul Central al Partidului Comunist, care tot “pătură” se voiau, după ce se cocoţaseră în copacul nomenklaturistilor, ca scroafa din poveste. Ori, din cele 60 de locuri dela Şcoala de Arhitectură, 20%, alocate pentru săraca “pătură”, reprezentau doar 12 locuri, pentru care concurenţa era acerbă, cu sute de candidaţi din toată ţara. Examenele de desen artistic şi desen tehnic erau eliminatorii si precedau faza a doua cu examenele de fizică şi matematică. Nota la desen era definită bineinteles de criterii politice, bazate pe origina socială, cu o pondere în funcţie de apartenenţa părinţilor la partidul comunist, proprietăţile naţionalizate şi altele, care nu îmi măreau deloc şansele, ba dimpotrivă Ca să echilibrez acest dezavantaj, luam lecţii particulare de fizică şi matematică în timpul săptămânii şi cinci ore de desen, în fiecare duminică. Totul a fost în zadar, căci nu aveam, prin definiţie, nici o şansă realistă de a trece de proba eliminatorie la desen, care fiind subiectivă, putea fi manipulată în funcţie de prejudecăţiile sau constrângerile politice ale exeminatorilor şi nu pe criterii obiective.

Pentru tatăl meu situaţia era clară şi atunci a inisistat să accept realitatea, ori cât de dureroasă ar fi fost ea şi să mă îndrept spre o carieră ştiinţifică: aici cel puţin rezultatele examenelor erau inechivoce şi nu puteau fi interpretate în funcţie de criterii politice. In acelasi context trebuie să nu uităm că in ponderea de admitere, un factor preponderent era si un parametru bazat pe o evaluare socio-politică a candidatului, special definită ca să minimalizeze admiterea in Universităţi a candidaţilor proveniţi din clasa intelectuală ne-integrată in randurile Partidului Comunist Român. Era ironic să mă gândesc că deşi la baccalaureat aveam rezultate slabe (chiar la limită) la fizică şi geologie, care nu ma interesau, în anul următor aveam să mă prepar pentru examenul de admitere la geofizică, la Facultatea de Geogie, a Institutului de Petrol şi Gaze din Bucureşti. Aici erau mai puţini candidaţi decât la Arhitectură, doar 5,5 pe un loc, dar cum soluţiile ecuaţiiilor erau unice, aici puteam demonstra în mod inechivoc cunostiinţele mele la Fizică şi Matematică. Tatăl meu a răsuflat uşurat să mă vadă admis la intrarea în facultate, într-o perioadă în care educaţia devenise un simbol existenţialist al supravieţiuirii, iar familia pierduse toate economiile şi investiţiile. Mai mult decât atâta, în clasa noastră socială, ca şi în toate familiile de intelectuali din Europa Centrală şi de Răsărit, ajunsesem la “sapă de lemn” si deci educaţia devenise un simbol al rezistenţei anticomuniste…

Aşa am ajuns să fiu geofizician.

Notă de Subsol: Extras din volumul publicat în limba engleză sub titlul:

“Continental Drift – Colliding Continents, Converging Cultures” apărut iniţial în limba engleză, la Institute of Physics, Bristol & Philadelphia, 2000,

ISBN-13: 978-0750306867

ISBN-10: 0750306866